During President Barack Obama’s address to world leaders at the Paris climate conference Monday, he cited, in unspecified terms, his rejection of the Keystone XL oil pipeline as evidence that the U.S. is doing its part to lower worldwide emissions. “We’ve said no to infrastructure that would pull high-carbon fossil fuels from the ground.” he said.

This little factoid has already gotten lost in the series of opening speeches that author Rebecca Solnit has called a “parade of clichés.” But it should stand out as a pretty remarkable thing—rejecting a pipeline is just plain weird.

A look at America’s history of building pipelines shows just how unusual Obama’s Nov. 6 rejection of Keystone was. We’ve been building oil pipelines for 150 years (the first came in the form of wooden gutters built in the 1860s), yet as a nation we’ve never made much of a hullabaloo over one, save the Alaska pipeline in the 1970s, which was eventually built.

The rejection is even more remarkable considering the number of pipelines in the country: According to the Bureau of Transportation Statistics, there are 150,000 miles of oil pipelines in the U.S. Add gas pipelines and we have more than 1.7 million miles of pipe.

Obama’s move could be considered a watershed moment in environmental history, yet in his Nov. 6 speech there was no soaring rhetoric—just pragmatic frankness about how this rejection will give the U.S. more credibility in the climate talks. The pipeline, he said, had taken on an “overinflated role in our political discourse.”

For years, proponents of the pipeline have said similar things. According to them, opponents have been wasting their time because the pipeline, in a world crisscrossed by pipes, wouldn’t make much of a difference on emissions and we might as well take the 50 permanent jobs. This impression was all but validated by the State Department’s environmental impact statement published in January 2014.

But the impact statement failed to take into account the human component of a movement. What will it mean for the spirit of a movement if it, for the first time, succeeds in stopping a pipeline? Will such a victory inspire other groups to take on other pipelines? Could a bolstered, more confident movement shift its focus to, say, ending oil transported by rail, and, in the long run, affect emission numbers in a roundabout way?

Every movement needs symbols, litmus tests and roles. It needs clear-cut battles and clear-cut victories. Movements need a Selma to get to a Civil Rights Act, a Stonewall to get to gay marriage, a Boston Tea Party to get to independence. These events don’t lead straight to legally sanctioned justice. Rather, they function as small steps forward. They’re things movements can hang their hats on.

The rejection of the pipeline will not bring the fossil fuel industry to a screeching halt, nor has it become a global rallying point at the climate talks. But the fight over it has started a new trend in pipeline opposition. What were once normal and never-before-questioned conveyances of energy are now facing unprecedented levels of scrutiny, ire and resistance.

Citizens across the continent, concerned about loss in property values, unmanageable oil spills and climate change, are taking on one of the most powerful industries in the world—the fossil-fuel industry. Enbridge’s Northern Gateway pipeline in British Columbia and its Sandpiper pipeline in Minnesota have received stiff opposition from concerned citizens. Momentum of TransCanada’s 2,800-mile Energy East pipeline has stalled. Efforts to lay gas pipelines across the Northeast have been stymied, like Dominion Energy’s Atlantic Coast Pipeline, a 550-mile pipeline that would go through the states of West Virginia, Virginia, and North Carolina. Energy Transfer Partners’s Dakota Access pipeline is being fought in Iowa.

Perhaps the most unusual thing about these pipeline battles is who’s doing the fighting. These environmentalists aren’t just the young and the liberal from the East and West Coasts. They include older generations from conservative and rural Midwestern states not known for their environmental activism. For example, one of the groups that made headlines in the fight over the XL was the Cowboy and Indian Alliance, a collection of farmers, ranchers and Native Americans. No longer just the territory of college students and hippies, the environmental movement has welcomed scores of salt-of-the-earth landowners to its ranks and has industry leaders quaking in their wingtips.

America’s Natural Gas Alliance President Marty Durbin calls the intensification of opposition toward new energy projects “Keystone-ization.” Alexander J. Pourbaix, a TransCanada executive, said: “It would be naïve for any energy infrastructure company to think that this would be a flash in the pan.”

It’s true that plenty of pipelines have recently snuck under the radar, but the rejection of Keystone may mean that oil pipelines are destined to the outmoded fate of horse-drawn wood wagons and whaling ships sooner than imagined. And it’s not just oil pipelines: Coal has long been under siege, and there’s a growing unease over fracking. We may well be moving toward—albeit at a steady crawl—a future with far fewer fossil fuels.

In his Monday address, Obama said that one of the enemies of the climate conference is “cynicism.” Whatever happens in Paris, with the rejection of Keystone he’s given many of his supporters what he promised long ago: hope.

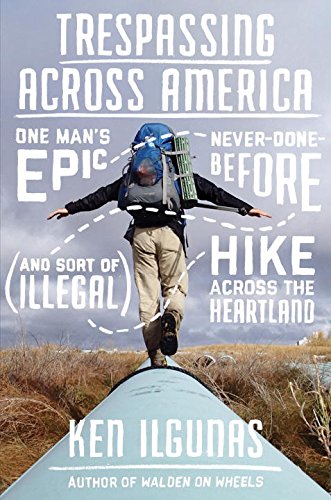

Ken Ilgunas is the author of Trespassing Across America: One Man’s Epic, Never-Done-Before (and Sort of Illegal) Hike Across the Heartland, about his walk along the route of the Keystone XL pipeline, to be published April 19, 2016 by Blue Rider Press.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com