These days, it’s easy to imagine how a news event that affects an entire country could be synthesized into a single news story. Social media networks making it possible to see what’s going on at a distance, and smartphones make it possible to send reports as the news is happening. But on this day, Dec. 7, in 1941, when the attack on Pearl Harbor launched the United States into World War II, writers at a magazine like TIME would have relied on typewriters and telegraphs.

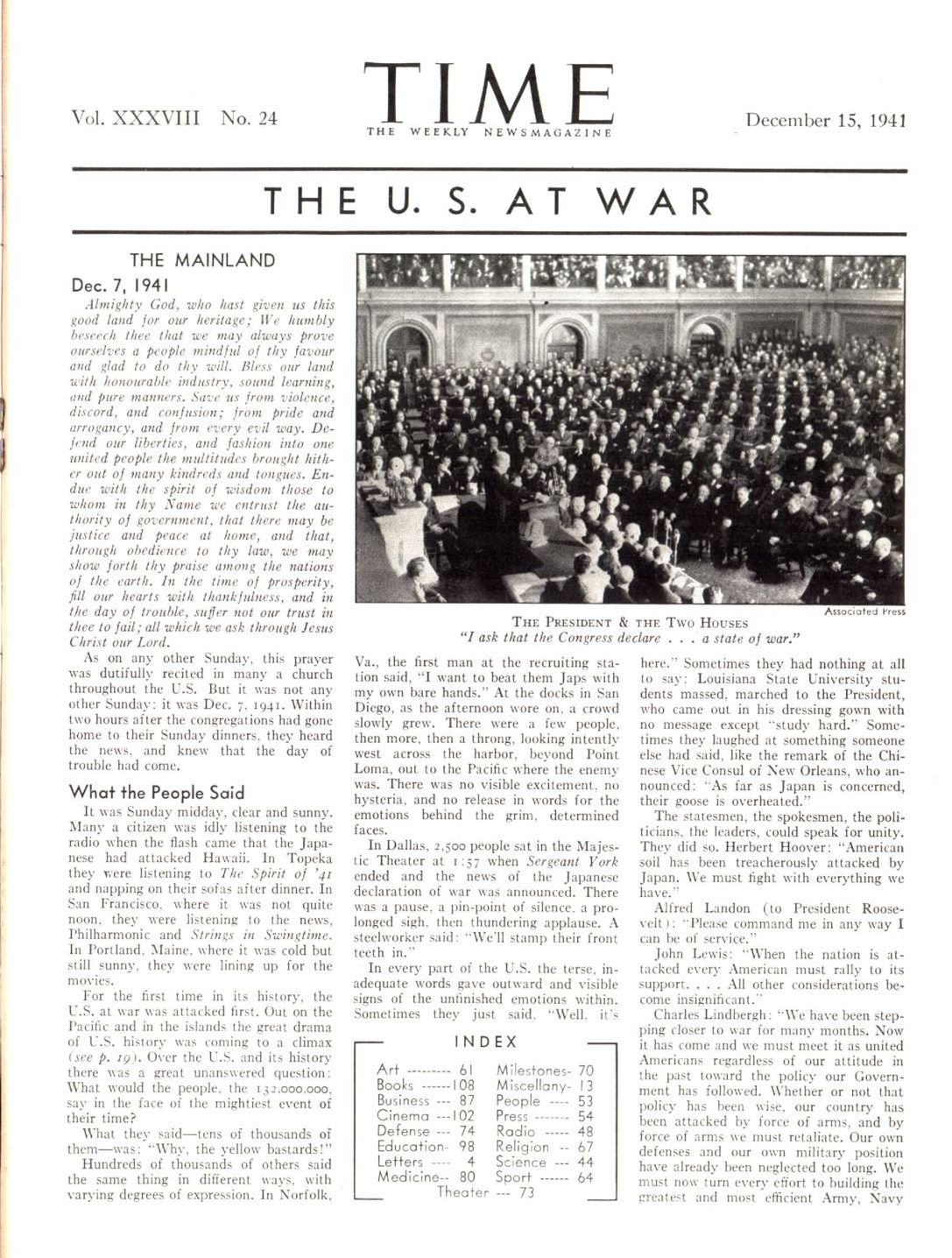

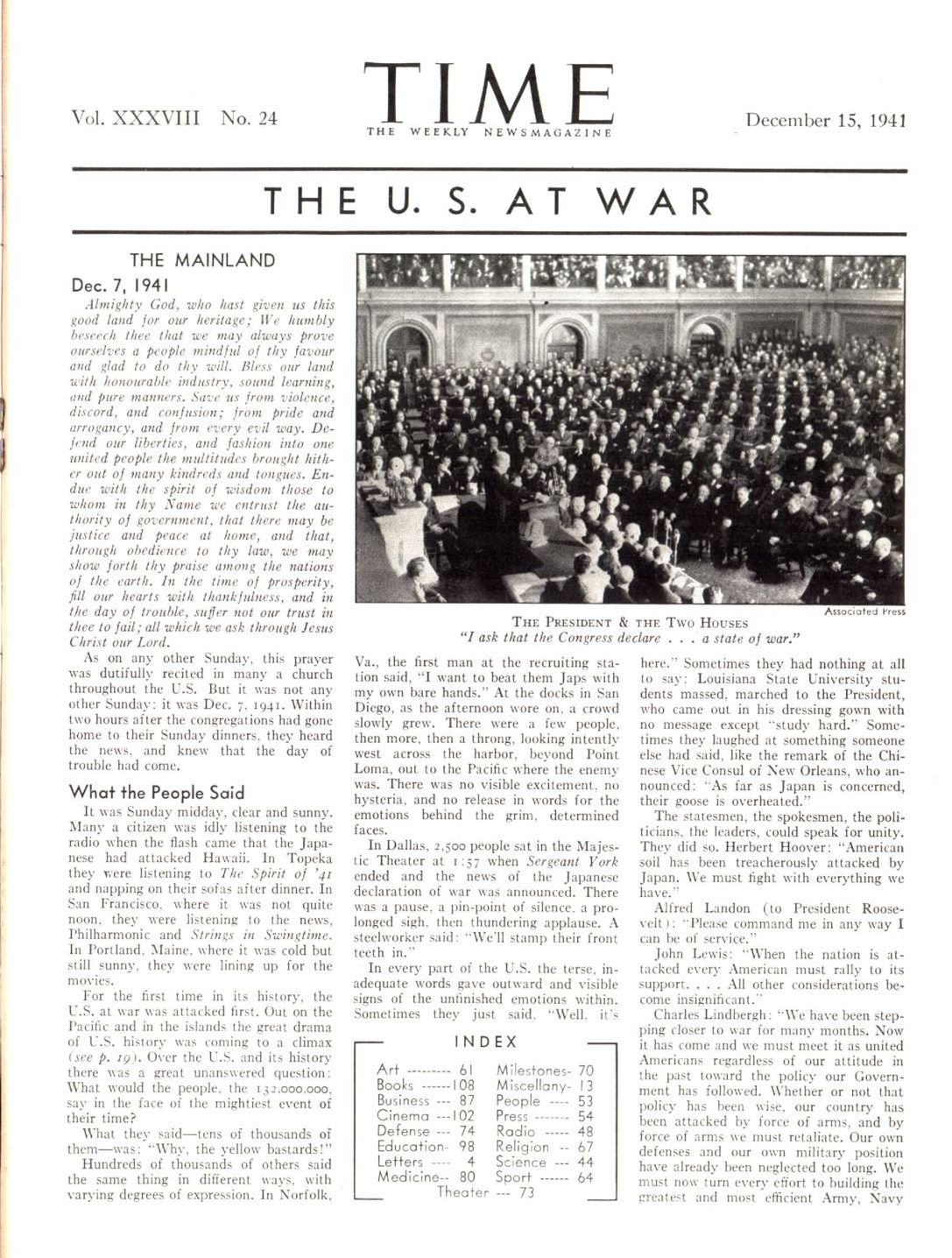

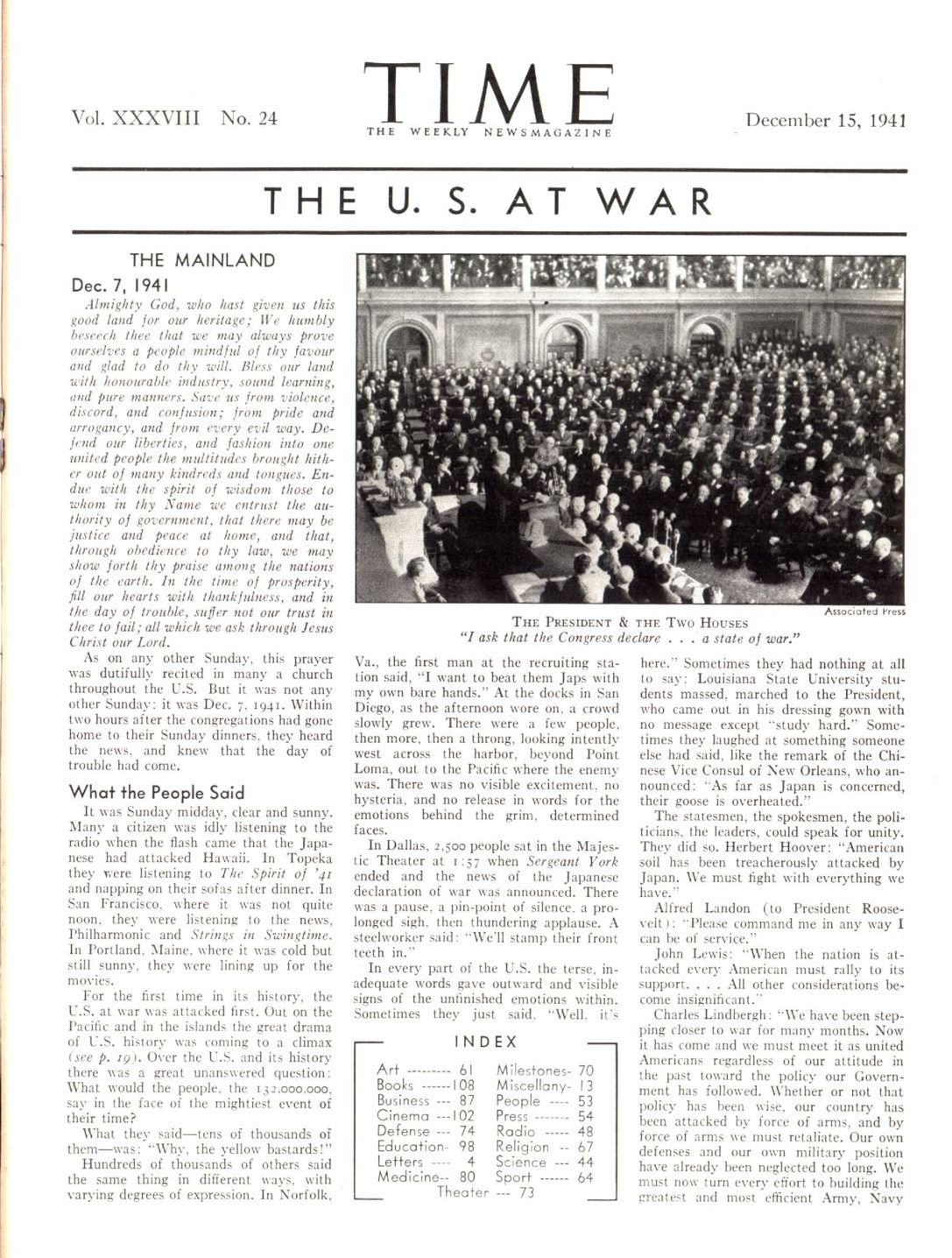

The week of Pearl Harbor, one of TIME’s feature stories on the attack, headlined “What the People Said,” traced reactions to the news from coast to coast. What were people doing when they found out what had happened? What did they say? How did the nation’s mood change in that moment? The finished article, a spare 767 words, was—as with most of the magazine’s stories at that time—unbylined. But behind the scenes was a staff of 200 people who worked at TIME, LIFE and Fortune news bureaus, including permanent offices in more than a dozen major cities and correspondents in over 100 other locations.

In later days, the company would put together a 222-page bound book comprising all of the cables sent by those staffers in first 30 hours after the attack. Those cables are full of “color” from all over the nation and the world, as well as newsier elements like first-hand accounts from inside the chambers of Congress.

And, thanks to those records, it’s possible to put together all of the puzzle pieces that contributed to the final story of war coming to the U.S.

In the following slides, the italicized text is the story that ran in TIME’s Dec. 15, 1941, issue. The images and transcriptions are from the reports made to News Bureau Chief David Hulburd during those tense hours.

What the People Said About Pearl Harbor

It was Sunday midday, clear and sunny. Many a citizen was idly listening to the radio when the flash came that the Japanese had attacked Hawaii. In Topeka they were listening to The Spirit of ’41 and napping on their sofas after dinner. In San Francisco, where it was not quite noon, they were listening to the news, Philharmonic and Strings in Swingtime. In Portland, Maine, where it was cold but still sunny, they were lining up for the movies.

For the first time in its history, the U.S. at war was attacked first. Out on the Pacific and in the islands the great drama of U.S. history was coming to a climax. Over the U.S. and its history there was a great unanswered question: What would the people, the 132,000,000, say in the face of the mightiest event of their time?

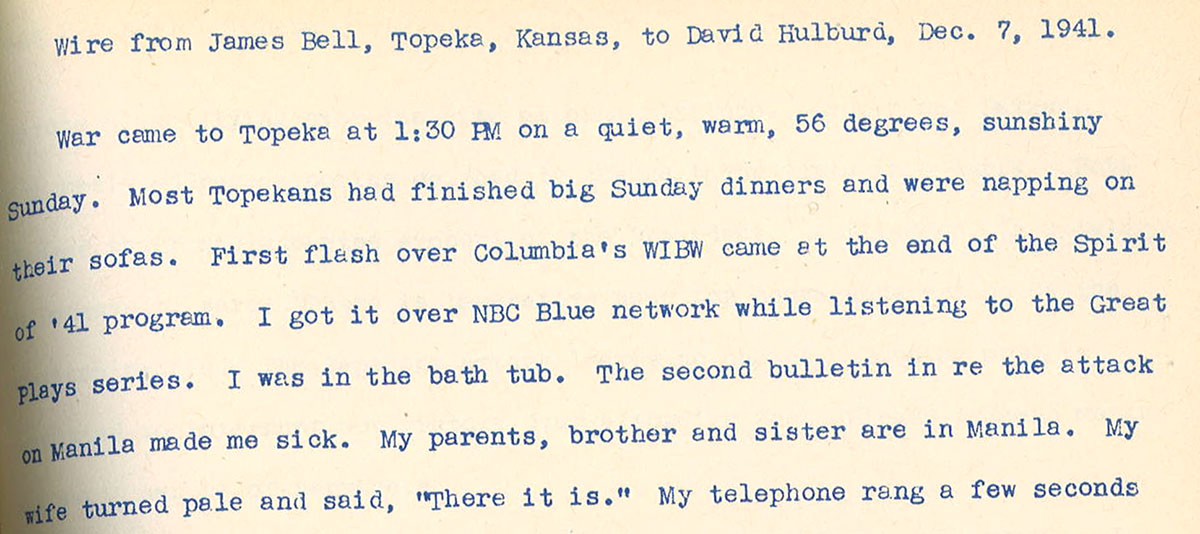

Report on Pearl Harbor From Topeka, Kans.

“War came to Topeka at 1:30 PM on a quiet, warm, 56 degrees, sunshiny Sunday. Most Topekans had finished big Sunday dinners and were napping on their sofas. First flash over Columbia’s WIBW came at the end of the Spirit of ’41 program. I got it over NBC Blue network while listening to the Great Plays series. I was in the bath tub. The second bulletin in re the attack on Manila made me sick. My parents, brother and sister are in Manila. My wife turned pale and said, ‘There it is.’ My telephone rang a few seconds later. I was called to help issue an extra and write “‘What it’s like over there’ story. Daily Capital switchboards were jammed immediately. One man, with distinct rural midwestern accent, asked: ‘What the Hell’s going on out there? Has Uncle Sam declared war yet? Why in Hell hasn’t he? How old do you have to be to get in the Army and Navy?’ Others wanted to know if it were true.”

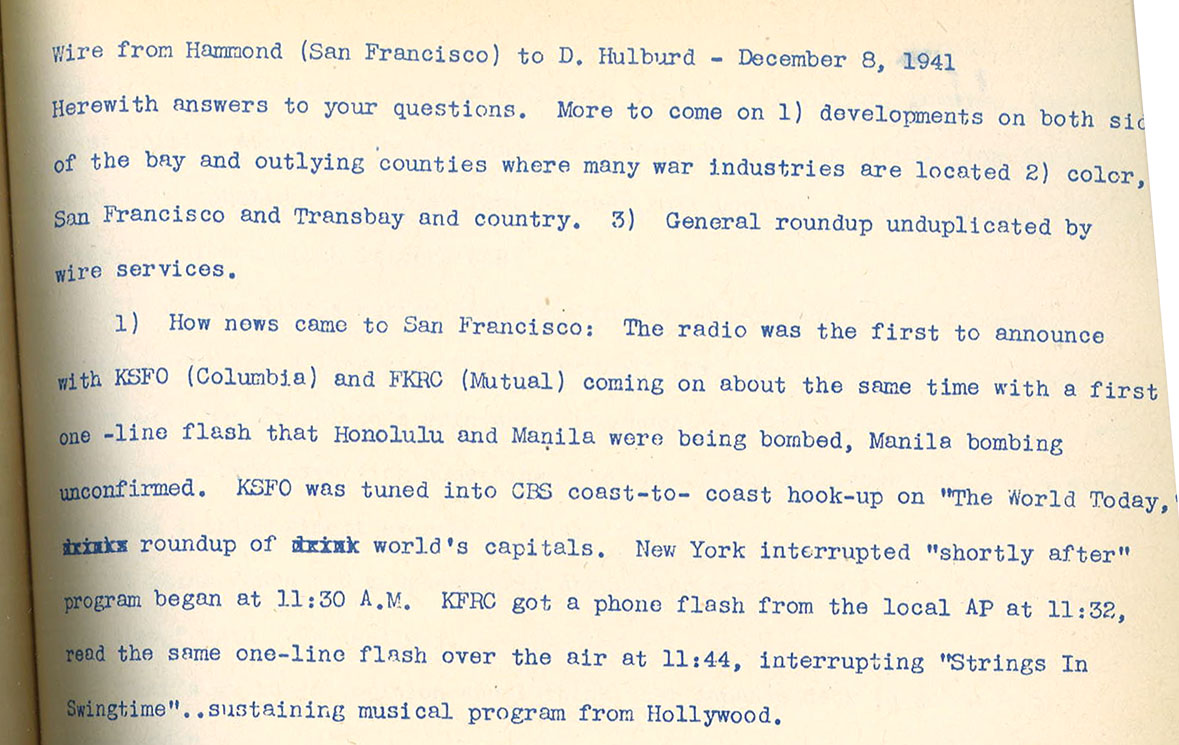

Report on Pearl Harbor From San Francisco

“How news came to San Francisco: The radio was the first to announce with KSFO (Columbia) and FKRC (Mutual) coming on about the same time with a first one-line flash that Honolulu and Manila were being bombed, Manila bombing unconfirmed. KSFO was tuned into CBS coast-to-coast hook-up on ‘The World Today,’ roundup of world’s capitals. New York interrupted ‘shortly after’ program began at 11:30 A.M. KFRC got a phone flash from the local AP at 11:32, read the same one-line flash over the air at 11:44, interrupting ‘Strings in Swingtime’..sustaining musical program from Hollywood.”

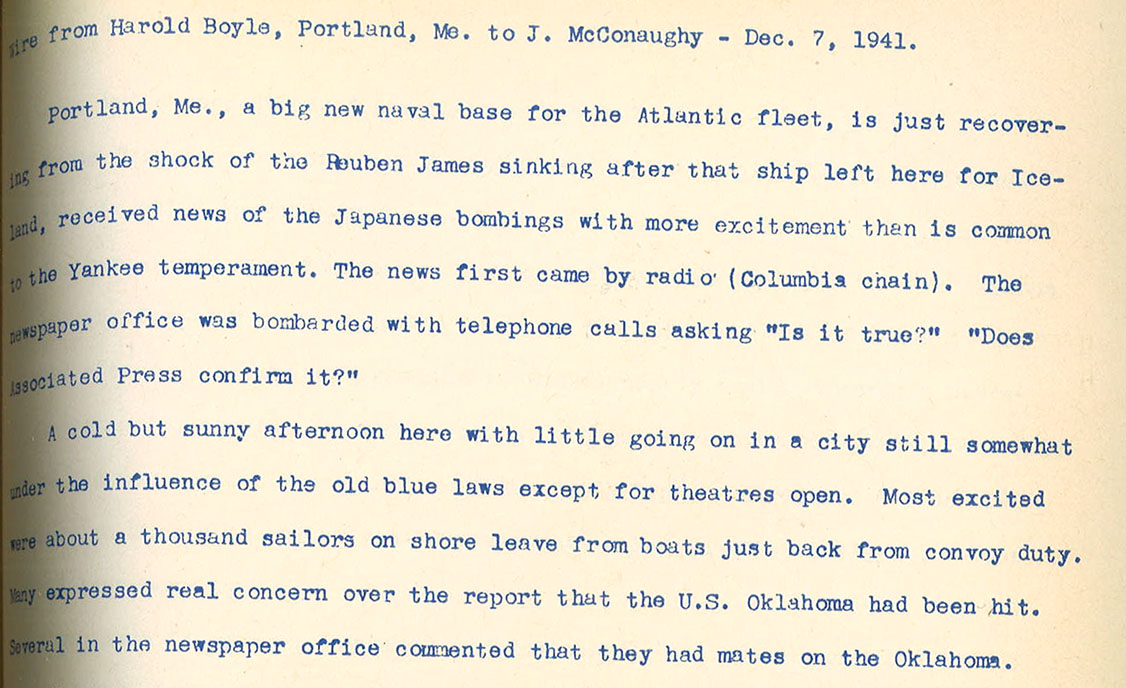

Report on Pearl Harbor From Portland, Me.

“Portland, Me., a big new naval base for the Atlantic fleet, is just recovering from the shock of the Reuben James sinking after that ship left here for Iceland, received news of the Japanese bombings with more excitement than is common to the Yankee temperament. The news first came by radio (Columbia chain). The newspaper office was bombarded with telephone calls asking ‘Is it true?’ ‘Does Associated Press confirm it?’

A cold but sunny afternoon here with little going on in a city still somewhat under the influence of the old blue laws except for theatres open. Most excited were about a thousand sailors of shore leave from boats just back from convoy duty. Many expressed real concern over the report that the U.S. Oklahoma had been hit. Several in the newspaper office commented that they had mates on the Oklahoma.”

‘Emotions behind the grim, determined faces’

What they said—tens of thousands of them—was: “Why, the yellow bastards!”

Hundreds of thousands of others said the same thing in different ways, with varying degrees of expression. In Norfolk, Va., the first man at the recruiting station said, “I want to beat them Japs with my own bare hands.” At the docks in San Diego, as the afternoon wore on, a crowd slowly grew. There were a few people, then more, then a throng, looking intently west across the harbor, beyond Point Loma, out to the Pacific where the enemy was. There was no visible excitement, no hysteria, and no release in words for the emotions behind the grim, determined faces.

In Dallas, 2,500 people sat in the Majestic Theater at 1:57 when Sergeant York ended and the news of the Japanese declaration of war was announced. There was a pause, a pinpoint of silence, a prolonged sigh, then thundering applause. A steelworker said: “We’ll stamp their front teeth in.”

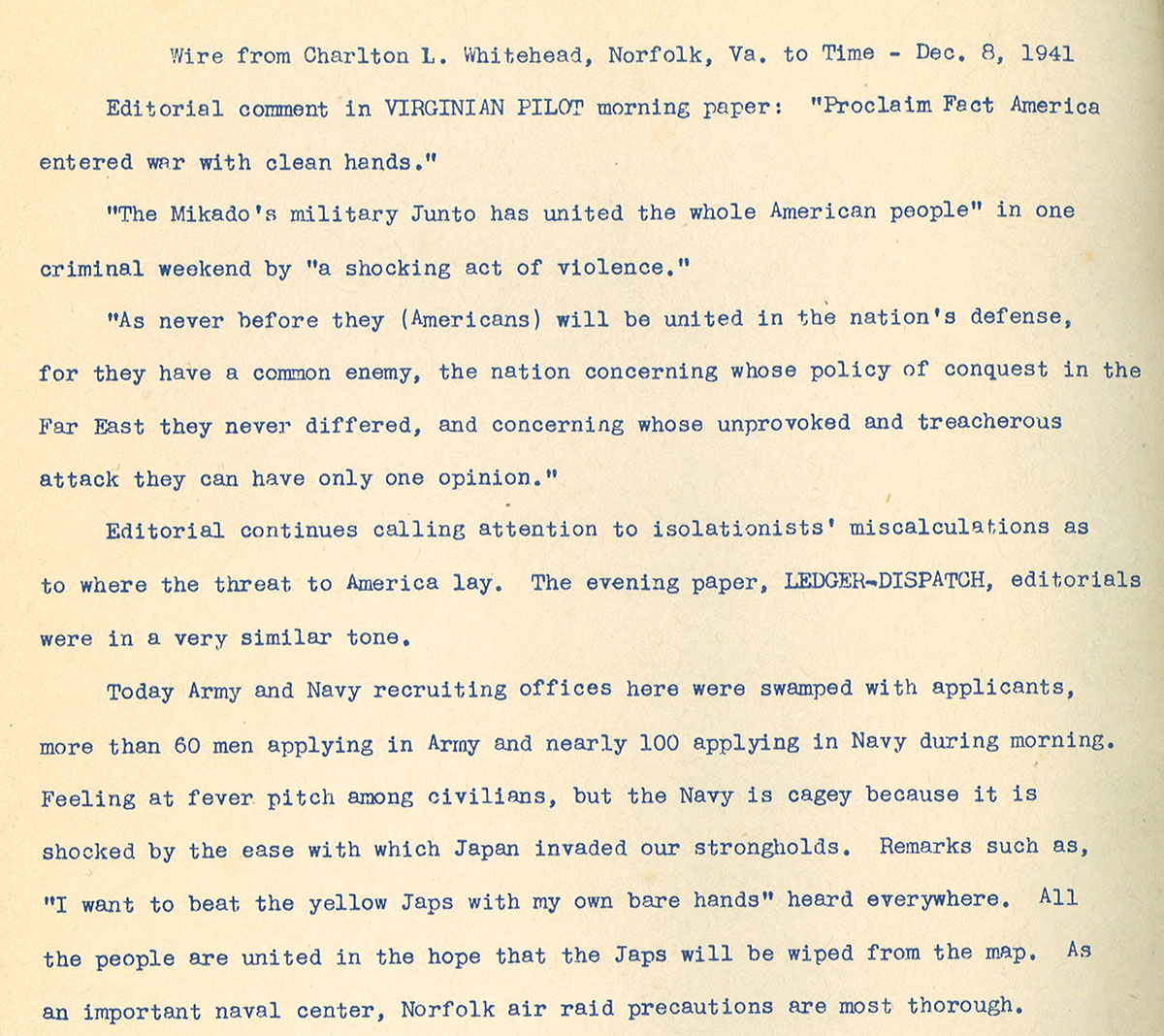

Report on Pearl Harbor From Norfolk, Va.

“Today Army and Navy recruiting offices here were swamped with applicants, more than 60 men applying in Army and nearly 100 applying in Navy during morning. Feeling at fever pitch among civilians, but the Navy is cagey because it is shocked by the easy with which Japan invaded our strongholds. Remarks such as, ‘I want to beat the yellow Japs with my own bare hands’ heard everywhere. All the people are united in the hope that the Japs will be wiped from the map.”

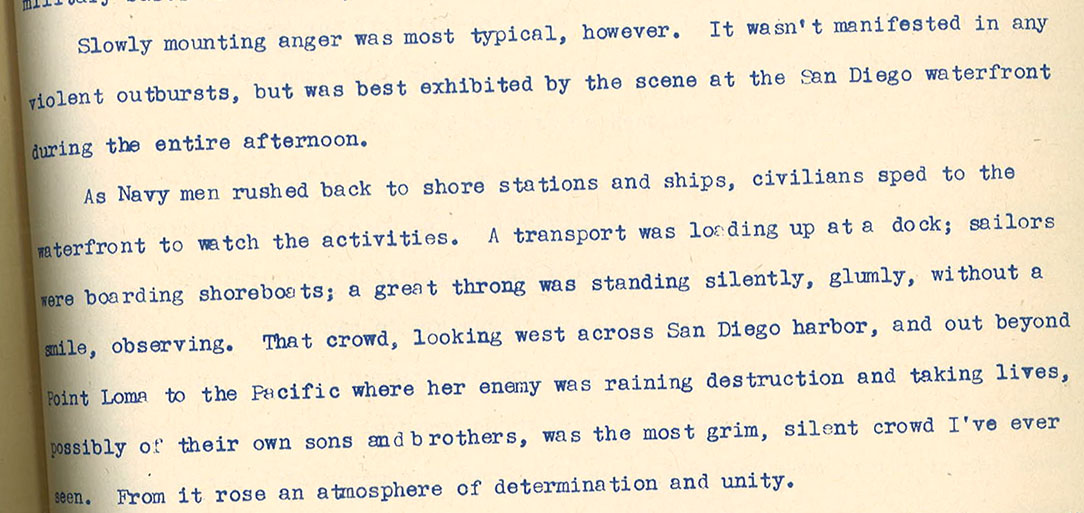

Report on Pearl Harbor From San Diego, Calif.

“Some reacted in forced humorous manner. ‘Wanna buy a house cheap?’ asked residents near the waterfront, where San Diego’s defense industries and navy and military bases are located, and where bombings, if any are likely to occur.

Slowly mounting anger was more typical, however. It wasn’t manifested in any violent outbursts, but was best exhibited by the scene at the San Diego waterfront during the entire afternoon.

As Navy men rushed back to shore stations and ships, civilians sped to the waterfront to watch the activities. A transport was loading up at a dock; sailors were boarding shoreboats; a great throng was stranding silently, glumly, without a smile, observing. That crowd, looking west across San Diego harbor, and out beyond Point Loma to the Pacific where her enemy was raining destruction and taking lives, possibly of their own sons and brothers, was the most grim, silent crowd I’ve ever seen. From it rose an atmosphere of determination and unity.”

Report on Pearl Harbor From Dallas

“Twenty-five hundred people sat in the Majestic Theatre at 1:57 Sunday afternoon. They had just watched the finish of probably one of the most dramatic war pictures of the year — Seargeant York. On the film flashed the title. Then there was a break in the sound and over the speakers came to announcement that Japan had attacked Pearl Harbor, Manila, Japan had declared a state of war with the United States. There was a pause, a pin-point silence, a prolonged ‘Awwwww’ and then thunderous applause.”

‘Sometimes they had nothing at all to say’

In every part of the U.S. the terse, inadequate words gave outward and visible signs of the unfinished emotions within. Sometimes they just said, “Well, it’s here.” Sometimes they had nothing at all to say: Louisiana State University students massed, marched to the President, who came out in his dressing gown with no message except “study hard.” Sometimes they laughed at something someone else had said, like the remark of the Chinese Vice Consul of New Orleans, who announced: “As far as Japan is concerned, their goose is overheated.”

Report on Pearl Harbor From New Orleans

“…He added jubilantly: ‘As far as Japan is concerned, their goose is overheated.’ He called from bath tub to the telephone after an attache had told a reporter: ‘He’s busy in the bath tub. What’s the trouble?’ From British Consul-General John David Rodgers: ‘It’s been a terrible day, hasn’t it?’

…

Louisiana State University students massed in Baton Rouge, marched to see President Major General Campbell B. Hodges, who came out in lounging robe and told them it was their duty to study hard. He envisioned a long war and said students would probably get their chance.”

‘Thus the U.S. met the first days of war’

The statesmen, the spokesmen, the politicians, the leaders, could speak for unity. They did so. Herbert Hoover: “American soil has been treacherously attacked by Japan. We must fight with everything we have.”

Alfred Landon (to President Roosevelt): “Please command me in any way I can be of service.”

John Lewis: “When the nation is attacked every American must rally to its support. . . . All other considerations become insignificant.”

Charles Lindbergh: “We have been stepping closer to war for many months. Now it has come and we must meet it as united Americans regardless of our attitude in the past toward the policy our Government has followed. Whether or not that policy has been wise, our country has been attacked by force of arms, and by force of arms we must retaliate. Our own defenses and our own military position have already been neglected too long. We must now turn every effort to building the greatest and most efficient Army, Navy and air force in the world. When American soldiers go to war, it must be with the best equipment that modern skill can design and that modern industry can build.”

It was evening. Over the U.S. the soldiers and sailors on leave assembled at the stations. There would be a few men with their wives or their girls standing a little apart. Sometimes there would be a good-natured drunk trying to sing. The women would cry or, more often, walk away stiffly and silently. Slowly, the enormity of what had happened ended the first, quick, cocksure response.

Next morning recruiting stations, open now 24 hours a day, seven days a week, were jammed too. New York had twice as many naval volunteers as its 1917 record.

Thus the U.S. met the first days of war. It met them with incredulity and outrage, with a quick, harsh, nationwide outburst that swelled like the catalogue of some profane Whitman. It met them with a deepening sense of gravity and a slow, mounting anger. But there were still no words to express emotions pent up in silent people listening to radios, reading papers, taking trains. But the U.S. knew that its first words were not enough.

Read the full issue from December 1941, here in the TIME Vault

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Trump’s Message Worked on Latino Men

- What Trump’s Win Could Mean for Housing

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Sleep Doctors Share the 1 Tip That’s Changed Their Lives

- Column: Let’s Bring Back Romance

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Lily Rothman at lily.rothman@time.com