It’s an old adage, sure. But on the Internet, it may as well be a scientific law: You don’t get something for nothing.

I re-learned this most recently when I tried to see what my most used words on Facebook were. Billed as a “quiz” by a South Korean startup named Vonvon, this viral sensation spread across the social web like digital wildfire last week. But when I connected my account to “Most Used Words,” I did what I always do with Facebook apps: denied it access to anything beyond my public profile information. And as a result, the word cloud it returned was blank.

Social media services like Most Used Words have long used personal user information to generate unique, interesting, and sharable posts. But in the case of Vonvon’s content, users have complained that the company stepped over the line by asking for far more data than the quiz seems to need. Specifically, Vonvon requested access to the following user data:

Since Monday, other users began taking notice of the fistfuls of data that Most Used Words seemed to be grabbing at. Then media outlets began reporting on it, with The Huffington Post calling the quiz “a breach of your personal data,” and WIRED dubbing it “a privacy nightmare.” And suddenly, Most Used Words’ meteoric viral climb slowed to a crawl. In its first five days, the quiz attracted 17.5 million users. In the past two, fewer than 300,000 have tried it.

I was among the people jarred by the apparent privacy overreach. But after some digging, I’m no longer sure Vonvon has done anything wrong, yet.

According to Vonvon President David Hahn, Most Used Words requested all of this user info because the company runs a wide range of quizzes, and it hoped people would return to the website daily to take more of them. By asking for permission for all of that user data up front, Vonvon wouldn’t have to repeatedly pester users for it again.

On top of that, Hahn contends, the company cannot store any user data itself. When a Facebook user interacts with Vonvon’s content, their information continues to reside in the social network’s servers, and Vonvon cannot copy the data. In fact, says Hahn, the only bit of data that Vonvon receives from connecting a user to its services is the user’s Facebook ID number, anonymized digits that let returning users access their results on the company’s various quizzes and viral content such as “Are You A Psychopath?” “Who has a crush on you?” and “Which Pixar Superstar Captures You Perfectly?”

In double-checking Hahn’s claims with Jeremy Gillula, staff technologist for the privacy group Electronic Frontier Foundation, it appears that Vonvon is indeed playing it safe with user data. Most Used Words, and the company’s other quizzes, seem to be run within the web browser in JavaScript, which means the data is parsed right there on the user’s computer, not far away in the cloud.

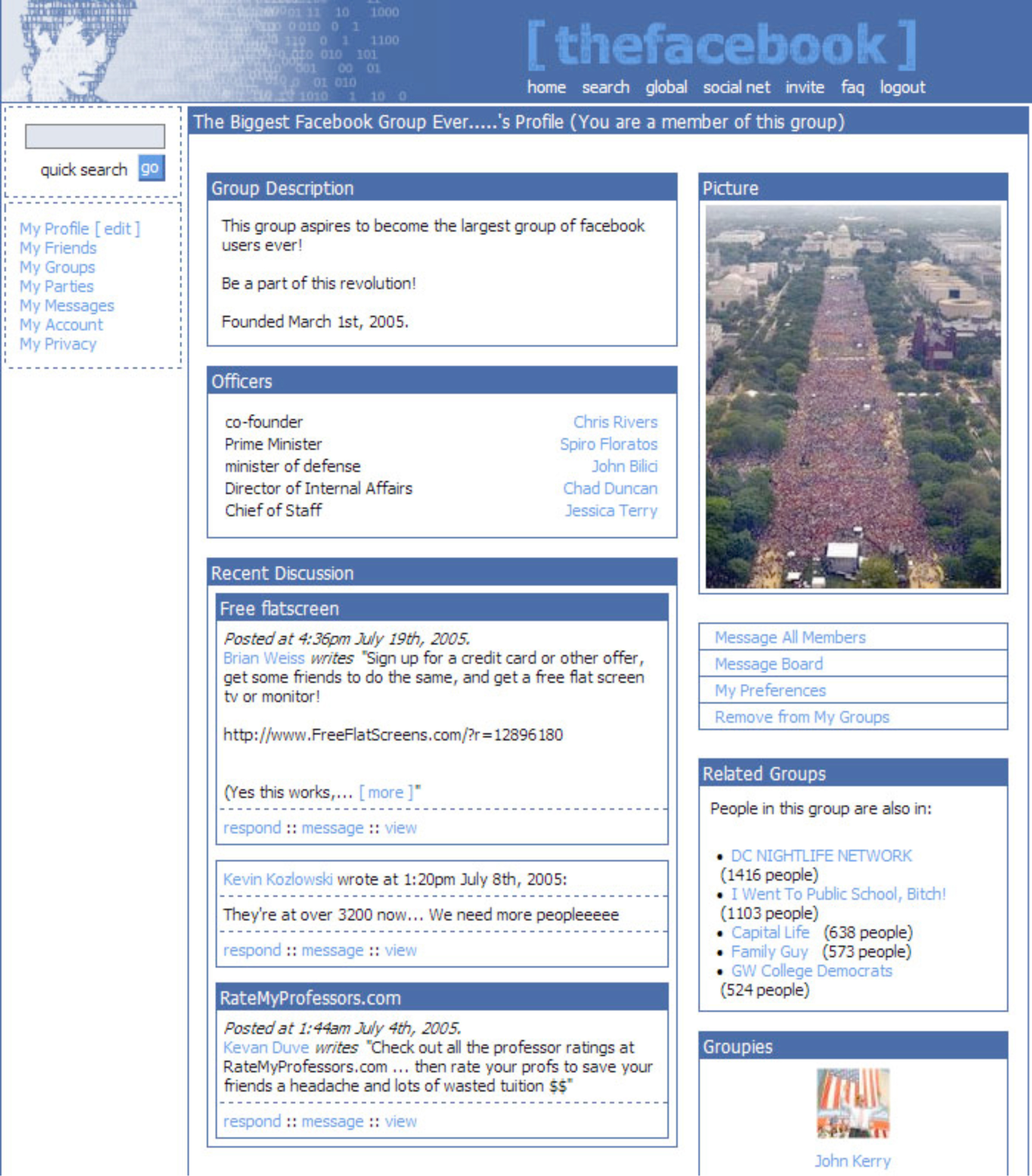

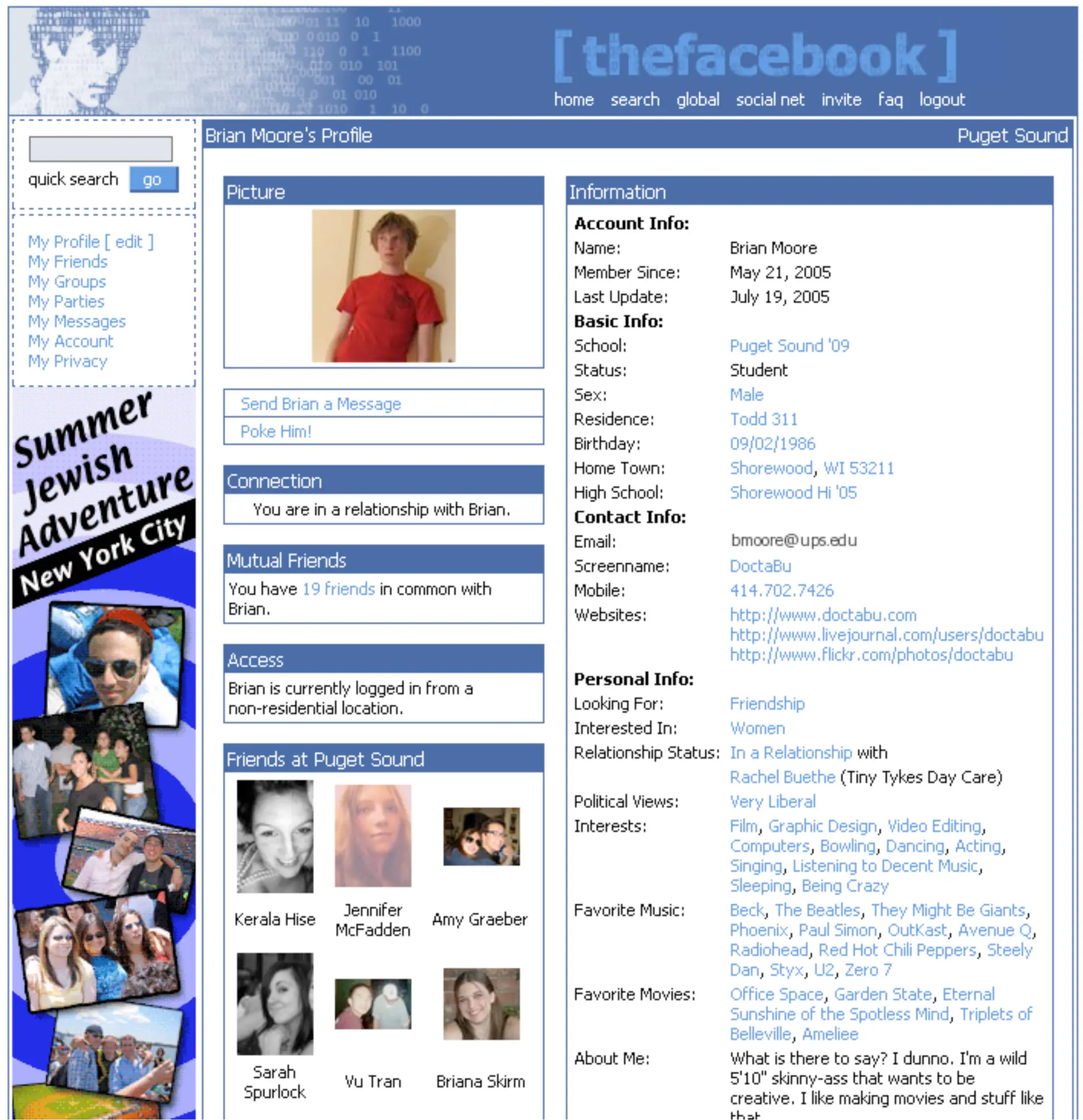

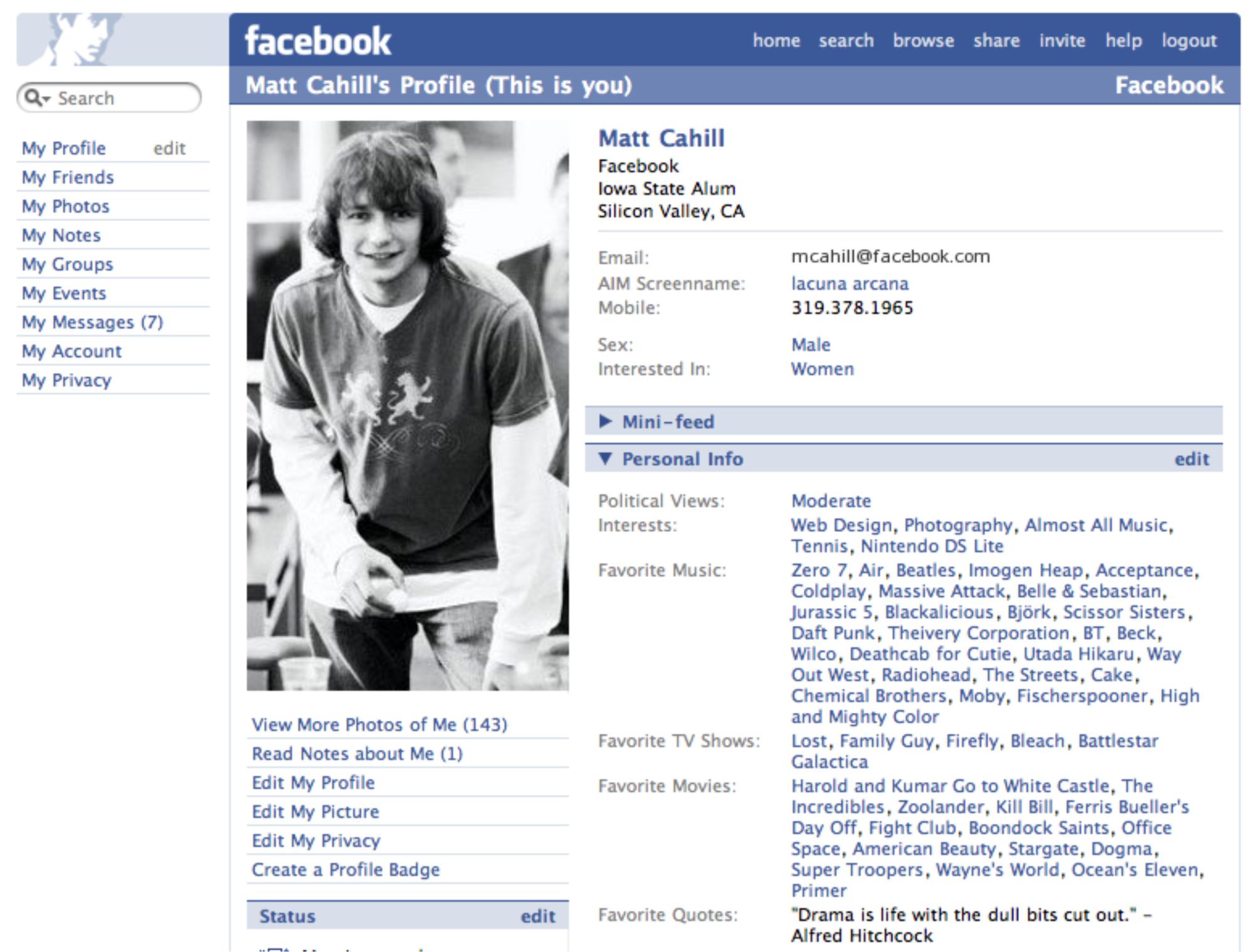

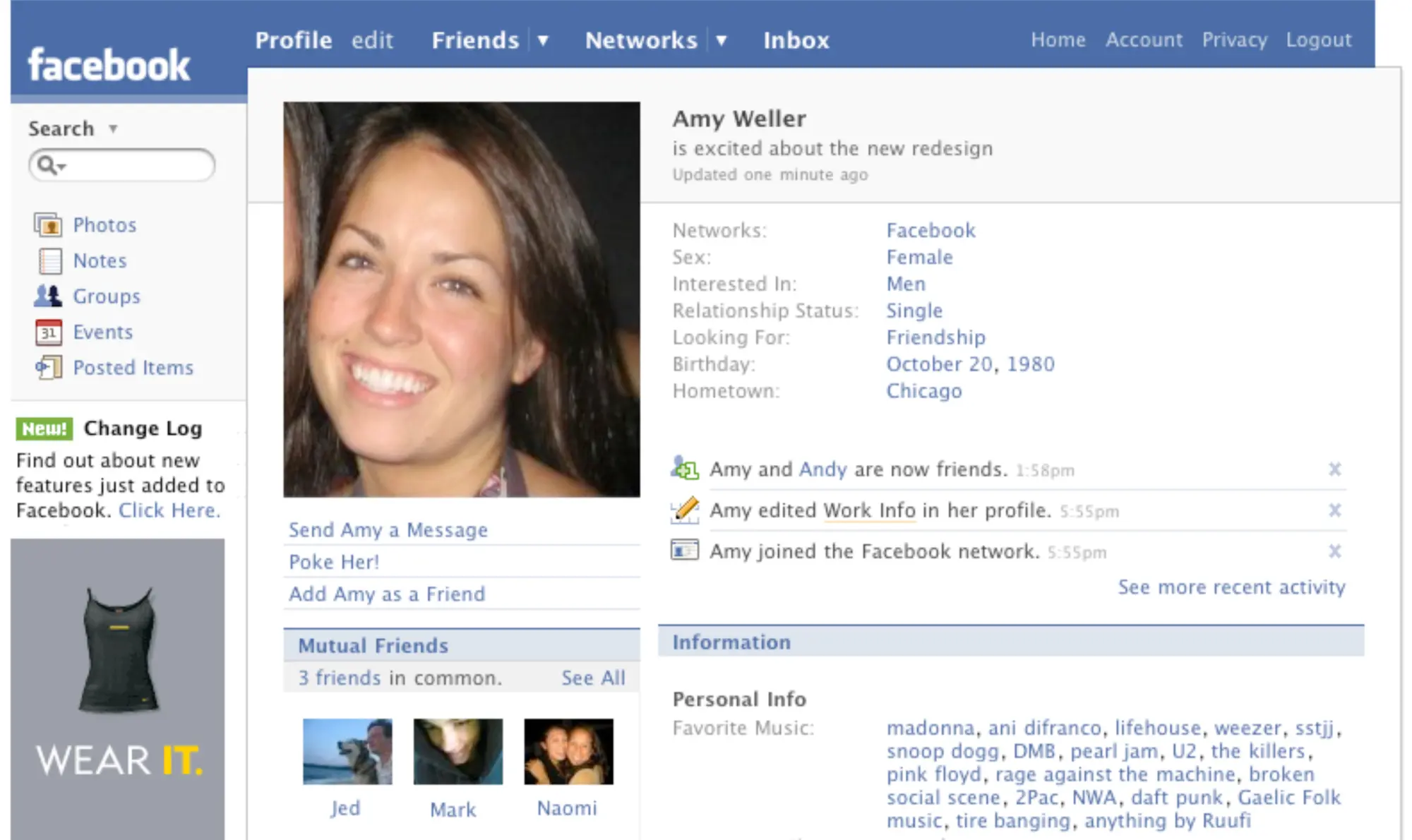

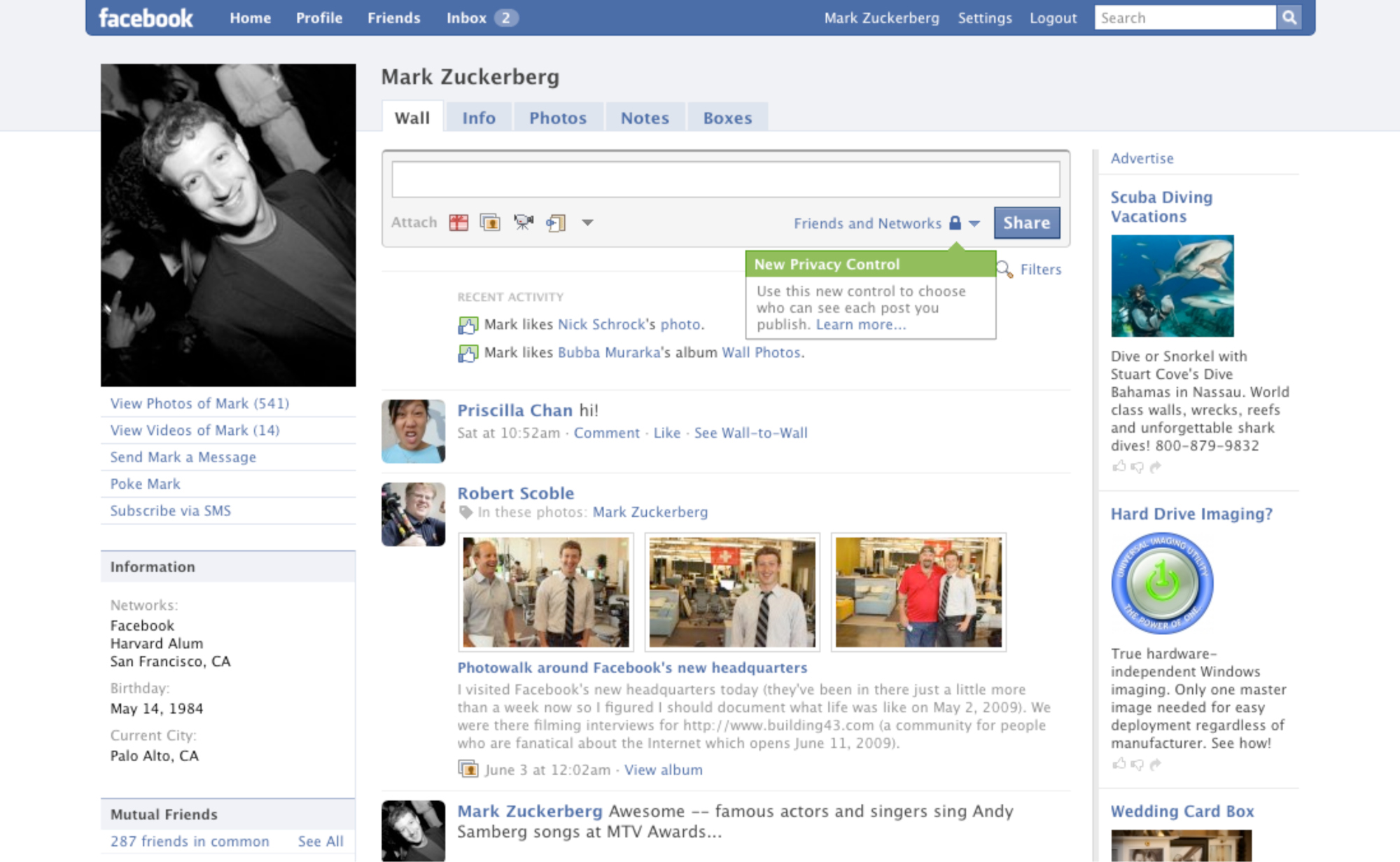

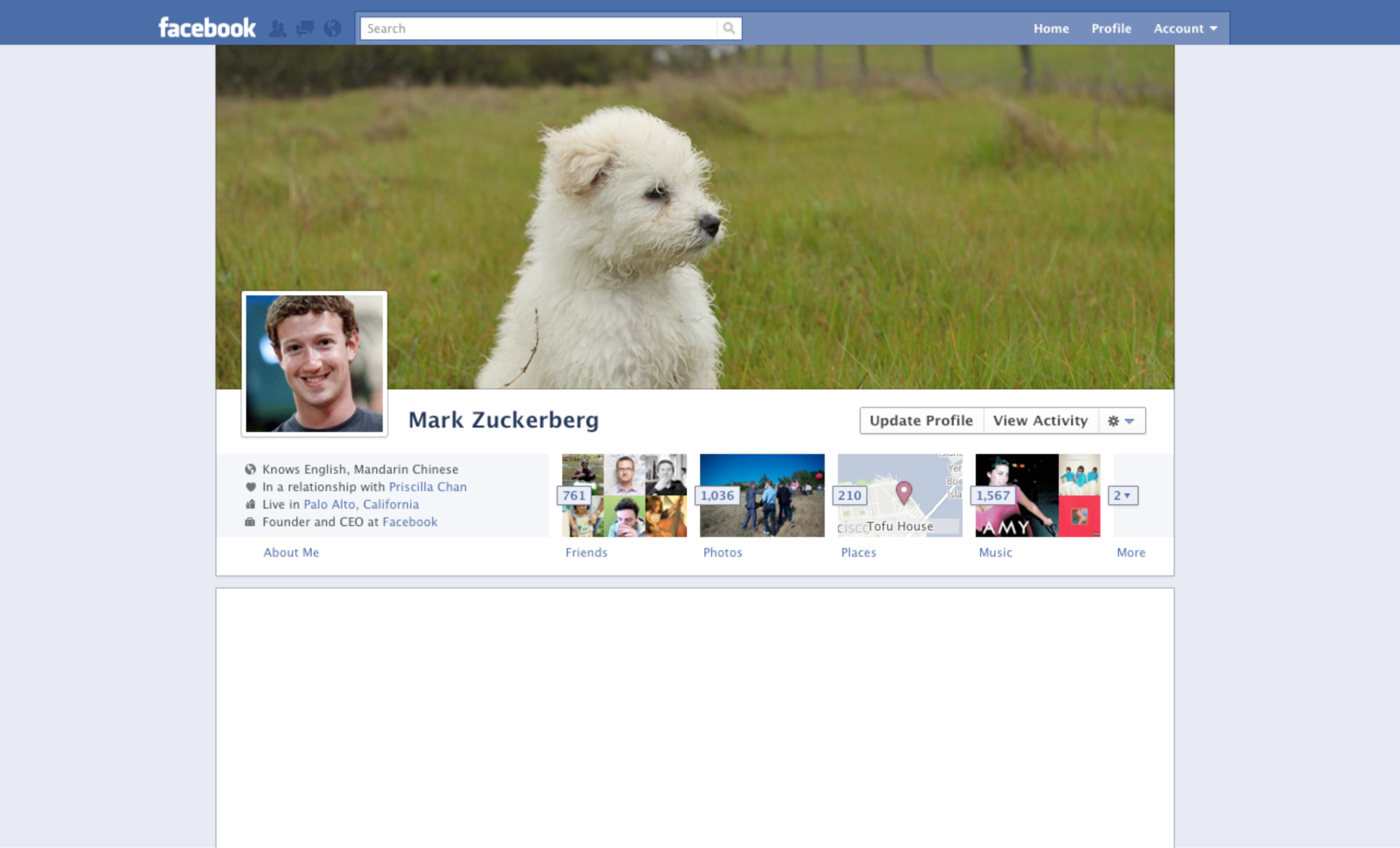

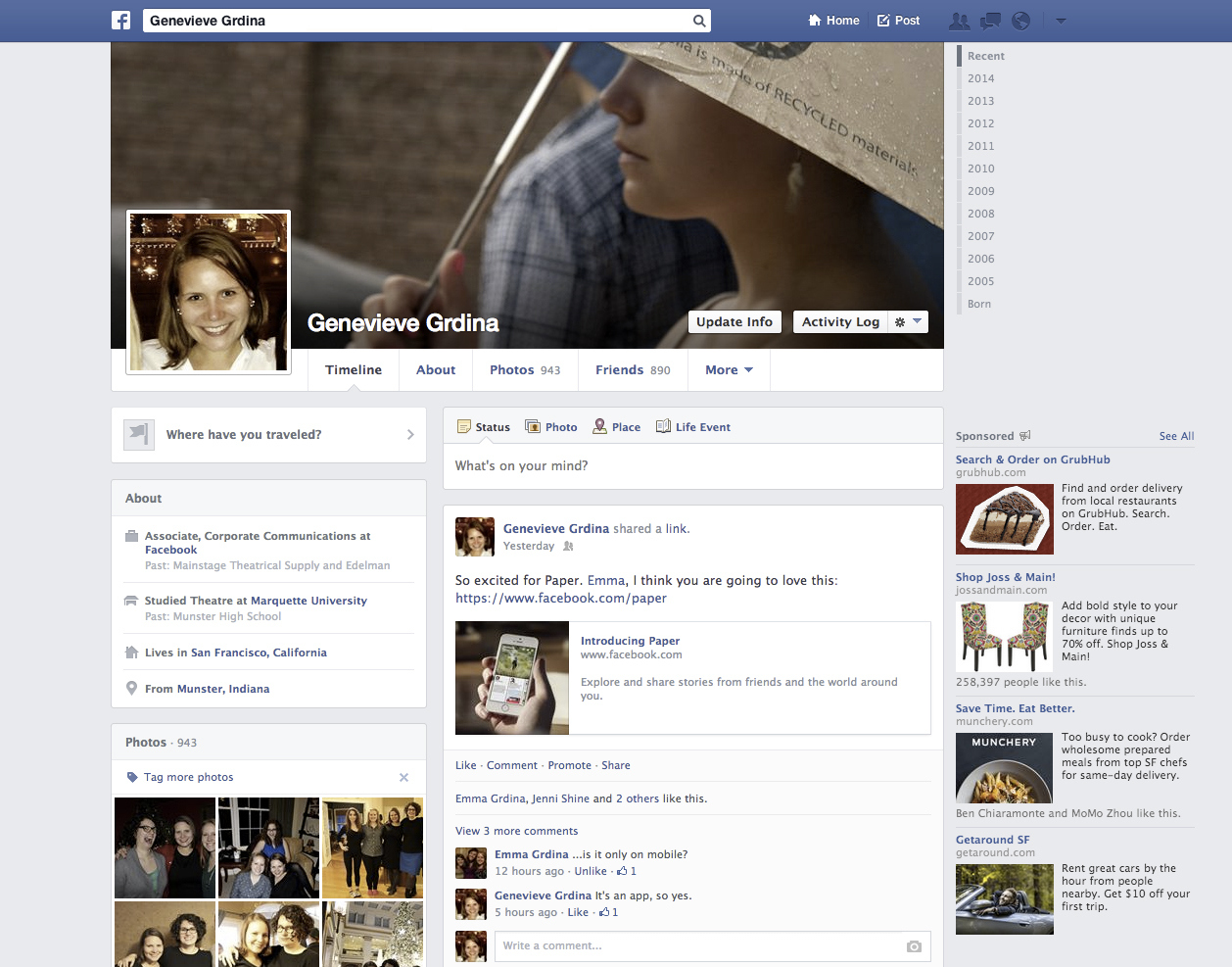

This Is What Your Facebook Profile Looked Like Over the Last 11 Years

“They are doing it in the most privacy protective way they could, given the limitations of Facebook’s API,” says Gillula. “At the same time, people may not realize that they don’t have to do it that way, and it’s entirely possible that they could have done it another way — a less conscientious developer could have done it differently.”

And that is the problem with my snap judgement. Good apps and nefarious ones can look too similar to the naked or uninformed eye. Even Gillula isn’t completely certain that Vonvon’s content isn’t siphoning data out, somehow. “Without looking at every single line of the code, you can’t be 100% sure,” he says. “There’s certainly no easy way for users to be sure.”

And as a startup trying to establish trust with a growing audience, Vonvon wants the public to see the company in a positive light. To date, Vonvon’s various pieces of viral content have resulted in more than 200 million user interactions across 15 languages since the company launched in March. It has $2.6 million in funding, and has attracted sponsored content partners including Samsung, Australia Tourism, and online gaming platforms. The company has said that it does not collect or sell user data, and that it only generates revenue through these sponsored partnerships and through ads placed within its viral content.

“We are dedicated to create fun, engaging, and innovative contents while respecting our users’ privacy, and we hope our users will trust us in our efforts to creating a fun and safe platform for everyone to use.” says Hahn.

In a move towards better establishing that trust, as of Monday night, Vonvon has changed Most Used Words to now only request access to users’ public information, friends list, and timeline data. The app still works if you deny it access to your friend list — and you should — but that’s a step in the right direction.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com