Why did Apple “think different?”

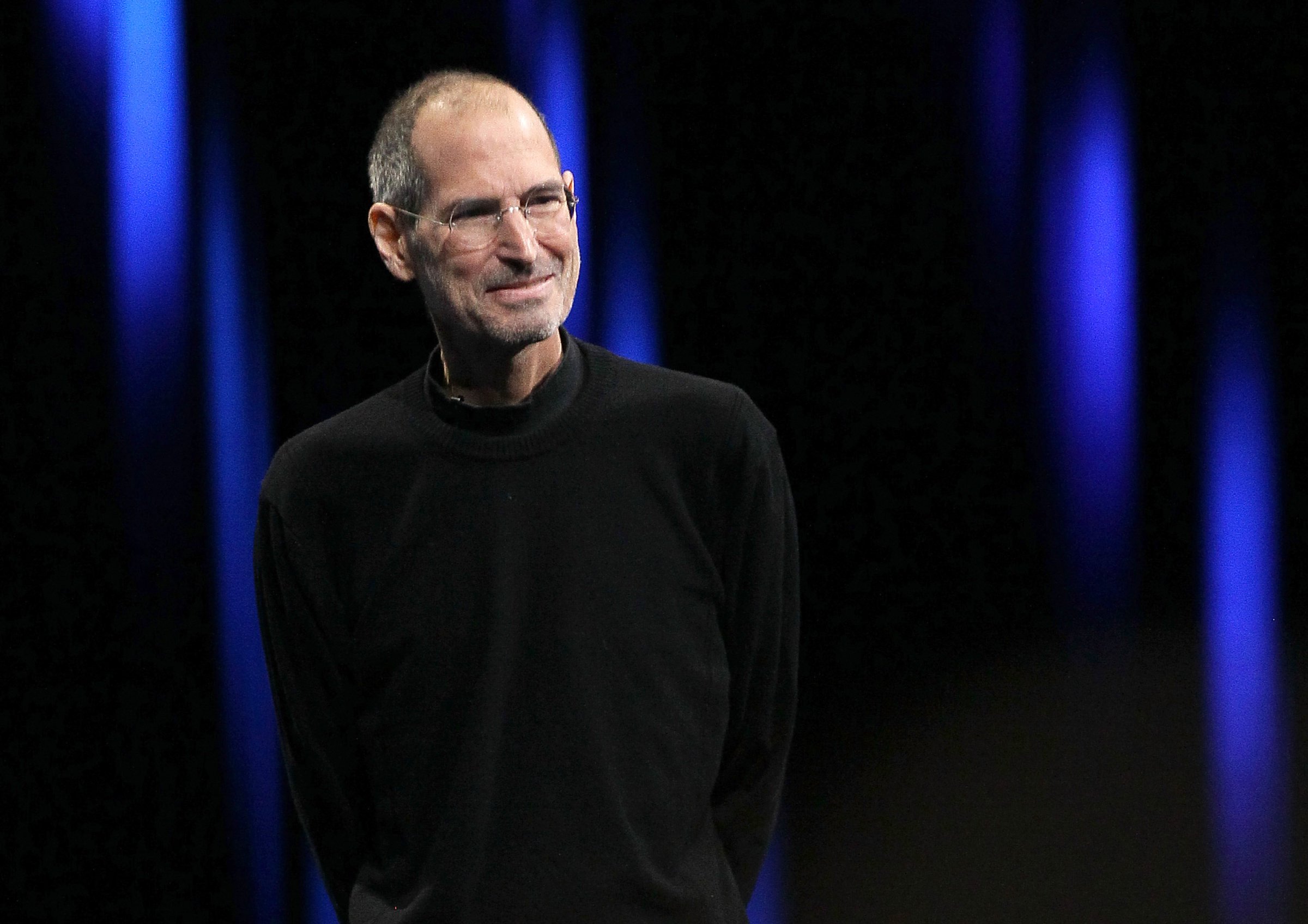

Because, Steve Jobs said while introducing the iPad, the Mac maker was never just a tech company.

“The reason that Apple is able to create products like the iPad is because we’ve always tried to be at the intersection of technology and the liberal arts,” he said.

Jobs’ lifelong interest in the humanities gave Apple a human touch.

By combining tech and the liberal arts, Jobs said that Apple was able to “to make extremely advanced products from a technology point of view, but also have them be intuitive, easy-to-use, fun-to-use, so that they really fit the users.”

Jobs arrived at that perspective through a lifetime of reading, as reviewed in Walter Isaacson’s biography and other places. We’ve put together a list of 14 books that most inspired him.

King Lear by William Shakespeare

Jobs really began his literary bent in the last two years of high school.

“I started to listen to music a whole lot,” he told Isaacson, “and I started to read more outside of just science and technology — Shakespeare, Plato. I loved King Lear.”

The tragedy may have provided a cautionary tale to a young Jobs, since it’s the story of an aged monarch going crazy trying to divide up his kingdom.

“King Lear offers a vivid depiction of what can go wrong if you lose your grip on your empire, a story surely fascinating to any aspiring CEO,” says Daniel Smith, author of How to Think Like Steve Jobs.

Moby Dick by Herman Melville

Another epic story colored Jobs’ outlook in his adolescence: Moby Dick, the deeply American novel by Herman Melville.

Isaacson draws a connection between Captain Ahab, who’s one of the most driven and willful characters in literature, and Jobs.

Ahab, like Jobs, did lots of his learning from direct experience, rather than relying on institutions.

“I prospectively ascribe all the honour and the glory to whaling,” the captain writes early in the story, “for a whale-ship was my Yale College and my Harvard.”

The Collected Poems of Dylan Thomas by Dylan Thomas

But the intellectual flowering that Jobs had in late high school wasn’t confined to hard-charging megalomaniacs — he also discovered a love for verse, particularly Welsh poet Dylan Thomas.

How To Think Like Steve Jobs author Daniel Smith says that Thomas’ poems “drew him in with its striking new forms and unerringly popular touch.”

“Do not go gentle” became a reported favorite:

Do not go gentle into that good night,

Old age should burn and rave at close of day;

Rage, rage against the dying of the light.Though wise men at their end know dark is right,

Because their words had forked no lightning they

Do not go gentle into that good night.

Be Here Now by Ram Dass

In late 1972, Jobs had just started at Reed College, an elite liberal arts school in Portland, Oregon.

Be Here Now, a guide to meditation by Ram Dass, affected Jobs greatly. Born Richard Alpert, Dass offers an account of his encounters with South Asian metaphysics:

Now, though I am a beginner on the path, I have returned to the West for a time to work out karma or unfulfilled commitment. Part of this commitment is to share what I have learned with those of you who are on a similar journey … Each of us finds his unique vehicle for sharing with others his bit of wisdom.

For me, this story is but a vehicle for sharing with you the true message, the living faith in what is possible.

“It was profound,” Jobs said. “It transformed me and many of my friends.”

Diet for a Small Planet by Frances Moore Lappe

In that first year at Reed, Jobs also read Diet for a Small Planet, a book about protein-rich vegetarianism that went on to sell three million copies.

It was a breakthrough.

“That’s when I pretty much swore off meat for good,” Jobs told Isaacson.

Mucusless Diet Healing System by Arnold Ehret

But Jobs’ diet grew more adventurous after reading Mucusless Diet Healing System by early-20th-century German dietitian Arnold Ehret, a guy who recommends practices like “intermittent juice fasting.”

“I got into it in my typical nutso way,” Jobs told Isaacson.

After getting to know Ehret’s work, Jobs became something of a nutritional extremist, subsisting on carrots for weeks at a time — to the point that his skin reportedly started turning orange.

Autobiography of a Yogi by Paramahansa Yogananda

Jobs read Autobiography of a Yogi by Indian yoga guru Paramahansa Yogananda when he was in high school.

Then he reread it while he stayed at a guesthouse in the foothills of the Himalayas in India.

Jobs explained:

There was a copy there of Autobiography of a Yogi in English that a previous traveler had left, and I read it several times, because there was not a lot to do, and I walked around from village to village and recovered from my dysentery.

The book remained a major part of Jobs’ life. He reread it every year.

Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind by Shunryu Suzuki

After Jobs got back from India, his interest in meditation continued to flourish. This is partly thanks to geography — 1970s California was the place where Zen Buddhism got its first foothold in America, and Jobs was able to attend classes led by Shunryu Suzuki, the Japanese monk who authored Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind.

Like everything else, Jobs went hard into Zen.

“He became really serious and self-important and just generally unbearable,” says Daniel Kottke, his best friend at the time.

“Zen has been a deep influence in my life ever since,” Jobs told Isaacson. “At one point I was thinking about going to Japan and trying to get into the Eihei-ji monastery, but my spiritual adviser urged me to stay here (in California).”

The Innovator’s Dilemma by Clayton M. Christensen

Apple made a habit of disrupting itself. The iPhone, for instance, had lots of the features of the iconic iPod, thus rendering the music device obsolete.

Jobs was able to see that that cannibalism was a necessary part of growth, thanks to the Innovator’s Dilemma by legendary Harvard Business School professor Clay Christensen.

The book posits that companies get ruined by their own success, staying committed to a product even after technology (and customers) move on, like Blockbuster did with physical movie rentals.

Jobs made it clear that the same thing wouldn’t happen to Apple, as he said in his explanation of why it needed to embrace cloud computing:

It’s important that we make this transformation, because of what Clayton Christensen calls “the innovator’s dilemma,” where people who invent something are usually the last ones to see past it, and we certainly don’t want to be left behind.

Cosmic Consciousness by Richard Maurice Burke

Kottke recently shared a list of the books he and Jobs read around their time at Reed — ones that inspired Jobs’s travels across the globe as well as his professional pursuits.

One of the most influential works on that list is Cosmic Consciousness: A Study in the Evolution of the Human Mind, originally published by a Canadian psychiatrist in 1901.

Based on his own supposed experiences with enlightenment, Burke makes the case for a higher form of consciousness than the normal person possesses. He outlines three forms of consciousness: the simple consciousness of animals and humans; the self-consciousness of humans, which includes reason and imagination; and cosmic consciousness, which transcends factual understanding.

You can read the full text online.

The Way of the White Clouds by Lama Anagarika Govinda

Buddhism was a tremendous influence in Jobs’s life, and it’s said that Zen philosophy helped inspire the simplistic design of Apple products.

Around the time they were beginning to explore Buddhism, Kottke said he and Jobs read this spiritual autobiography by a Buddhist who was one of the last foreigners to travel through Tibet before the Chinese invasion of 1950. Here the author recounts his experiences learning about Tibetan culture and tradition.

Ramakrishna and his Disciples by Christopher Isherwood

Kottke and Jobs’ literary exploration also included this biography of the 19th-century Hindu saint Sri Ramakrishna Paramahamsa, originally published in 1965.

Fans of the book say Isherwood refrains from preaching and from passing judgment on Ramakrishna’s teachings. Instead, he helps readers understand how the saint became so widely influential and revered by taking them on a journey from Ramakrishna’s childhood through his spiritual education.

You can read the full text online.

Cutting Through Spiritual Materialism by Chogyam Trungpa

This book was among those that Kottke and Jobs read while exploring Buddhist religion and philosophy.

It’s a transcript of two lectures the author gave, between 1970 and 1971, on common traps in spiritual journeys.

The main idea is that the ego, or the sense of self, is only an illusion. Instead of trying to improve themselves through spirituality, Trungpa urges readers to just let themselves exist.

You can read the full text here.

Meetings with Remarkable Men by George Ivanovich Gurdjieff

On their personal spiritual journeys, Jobs and Kottke derived inspiration from others who had embarked on similar quests for knowledge.

The second volume of the All and Everything trilogy, originally published in 1963, features the author’s recounting of people he met during his travels across Central Asia.

Gurdjieff, a Greek-Armenian spiritual teacher, sought spiritual and existential fulfillment in everyone from his father to a Persian dervish. One reader compares the work to a 20th-century version of the allegory Pilgrim’s Progress.

In 1979, the book was adapted into a film by the same name.

This article originally appeared on Business Insider

More from Business Insider:

More Must-Reads from TIME

- How Donald Trump Won

- The Best Inventions of 2024

- Why Sleep Is the Key to Living Longer

- Robert Zemeckis Just Wants to Move You

- How to Break 8 Toxic Communication Habits

- Nicola Coughlan Bet on Herself—And Won

- Why Vinegar Is So Good for You

- Meet TIME's Newest Class of Next Generation Leaders

Contact us at letters@time.com