When the lights went down for the first screenings of Toy Story across America on Nov. 22, 1995, audiences were merely eager to see how the first fully computer-animated movie had turned out. But the stakes were a bit higher for one particular team of people.

The movie was a joint venture between Disney and Pixar, a young company—then chaired by Steve Jobs—that had been recruited by the animation giant for its video capabilities. Pixar had been given a $26 million deal for three computer-animated, feature-length movies, but its filmmakers and engineers had yet to pull off a single one. Neither had anyone else for that matter. Succeeding would mean creating the software and hardware they would need as they went along, and inventing a new kind of movie altogether.

“At that point, none of us knew what we were doing. We didn’t have any production expertise except for short films and commercials. So we were all complete novices,” Ed Catmull, who was then a software engineer and is now Pixar and Disney Animation President, tells TIME. “But there was something fresh about nobody knowing what the hell we were doing.”

Catmull was a member of the Pixar “brain trust,” which also included current chief creative officer of Pixar and Disney Animation John Lasseter, the animator selected to direct Toy Story, and screenwriters Andrew Stanton and Pete Docter.

Reflecting on the experience 20 years later, Catmull notes that the young production studio was up against the wall: one project’s failure would likely mean the end of the three-movie contract, and the demise of Pixar studios.

“The entire company,” he says, “was bet upon us figuring this out.”

Spoiler alert: it was a good bet. The storytelling and technology of Pixar still rests upon the foundation Toy Story built. By the time the Toy Story credits started rolling that first day, the movies would never be the same.

The Toys

Catmull’s preparation started early. When he was a boy in Utah, he had watched early Disney movies with fascination, his eyes drinking in the color and magic of movement on the screens. All along, he had dreams of illustrating movies himself one day.

“We grew up with hand-drawn [animation], done the best at Disney Studios,” Catmull says. “It was very subtle and very emotional.”

He notes that part of what made the films so magical was how Walt Disney incorporated all the latest technology of his time, letting that innovation stimulate the illustrations. When it came to Toy Story, the animators didn’t have much choice but to follow Disney’s lead. No one had ever tried to make a feature-length film with 3D animation, so the technological capabilities guided much of their creative process, says Lasseter, who worked as an animator at Disney after college.

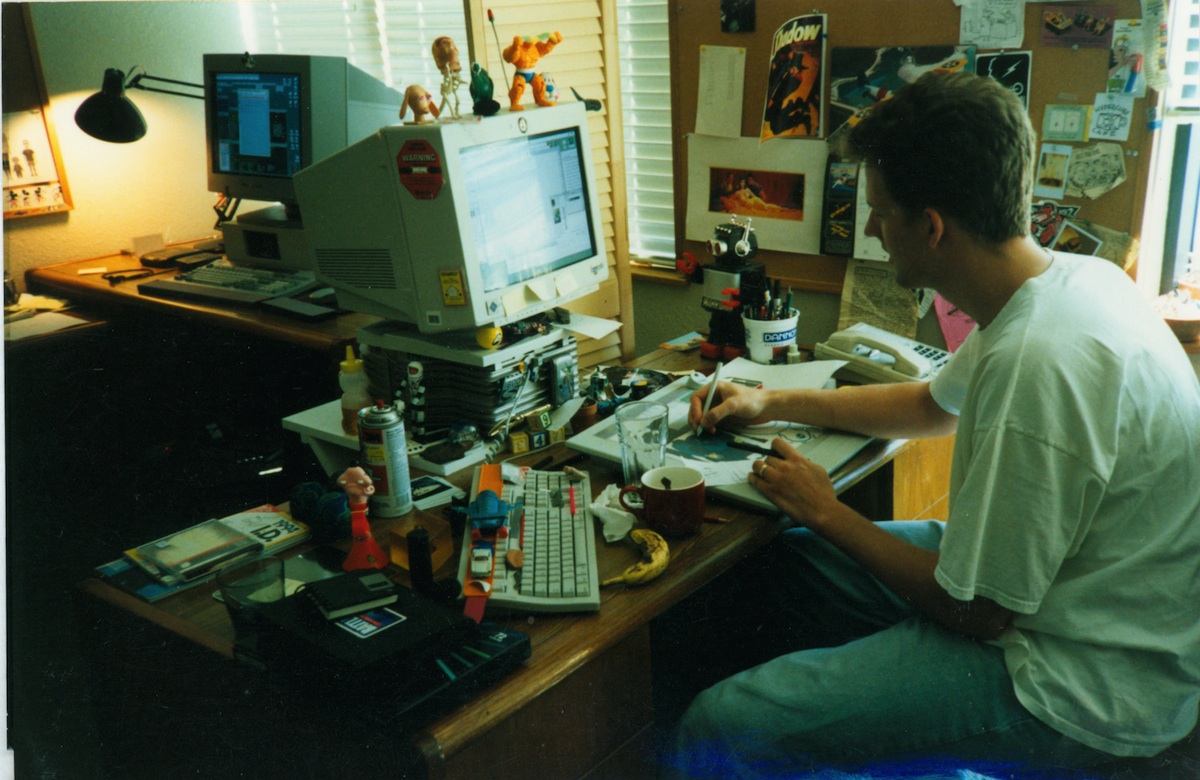

Catmull and computer scientists at Pixar built the software that animators could use to design the film, like RenderMan, which originated from Catmull’s studies at the University of Utah, and Menv (“modeling environment”), which the programmers developed for Pixar’s 1988 short Tin Toy. The goal was to allow the animators, without much engineering background, to control movement and “rig” their own characters.

In some ways, working with computers opened new possibilities, letting animators add details they never would be able to (or would want to avoid, to minimize illustrators’ “pencil mileage”), such as the plaid pattern on Woody’s shirt or the stickers on Buzz’s curved glass helmet.

But it had its limits—and that’s where the toys came in.

That software lent itself to perfectly geometric objects, such as blocks, bouncing balls: the type of things found in Andy’s stash of toys. Anything in a more “organic” shape or texture ended up looking plastic—which lent itself nicely to a movie about plastic objects springing to life. Toys always hung out in a kid’s room, Lasseter added, which let animators do their illustrations on a perfectly flat floor that was simple to render.

At first, the team was going to avoid humans altogether; choosing to keep them just out of the frames, Lady-and-the-Tramp-style, rather than crudely animating their features. Eventually human presence was too hard to avoid, and as a result viewers could put a face to Andy (a face that showed the improvements of Pixar’s rendering capabilities by the time he was off to college in Toy Story 3).

“I was so geeky and into this stuff,” Lasseter adds. “I’d always say ‘hey can we do this?’ They’d say ‘no, but let’s try,’ and they’d do R&D to get there. Meanwhile, all that R&D is inspiring different ideas. Then I’d say ‘oh can we do this with it?’ and come up with ideas we’d never thought of.”

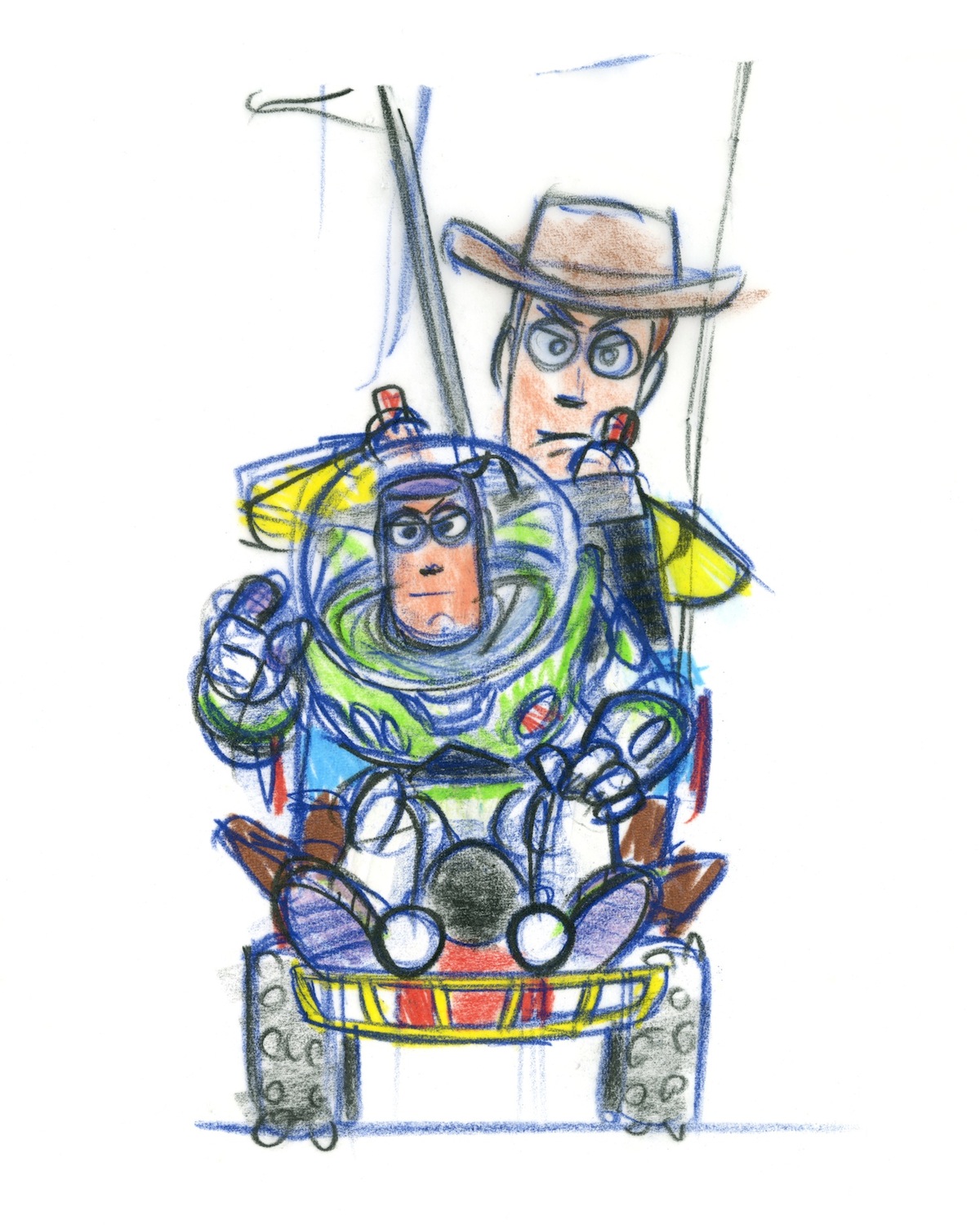

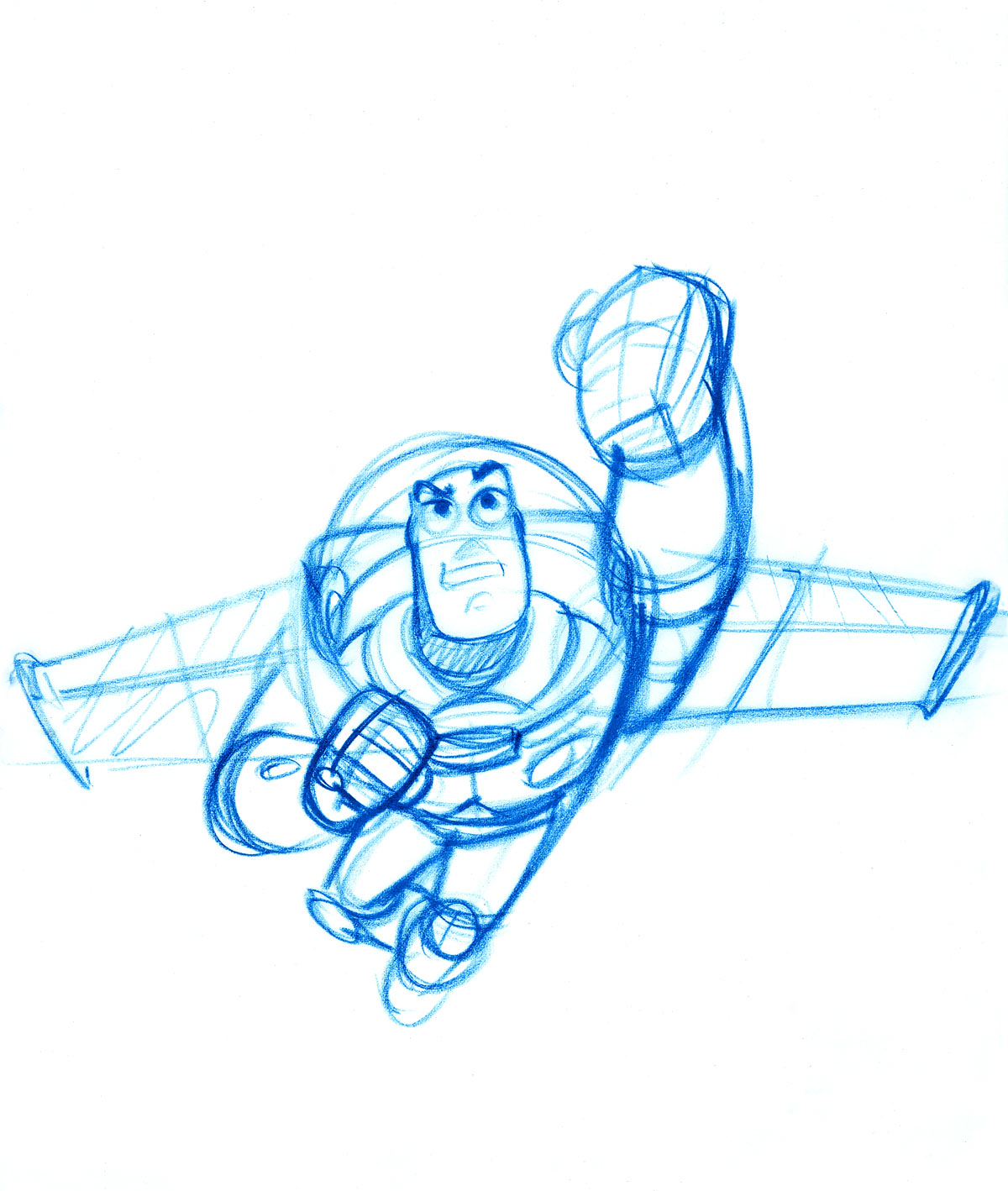

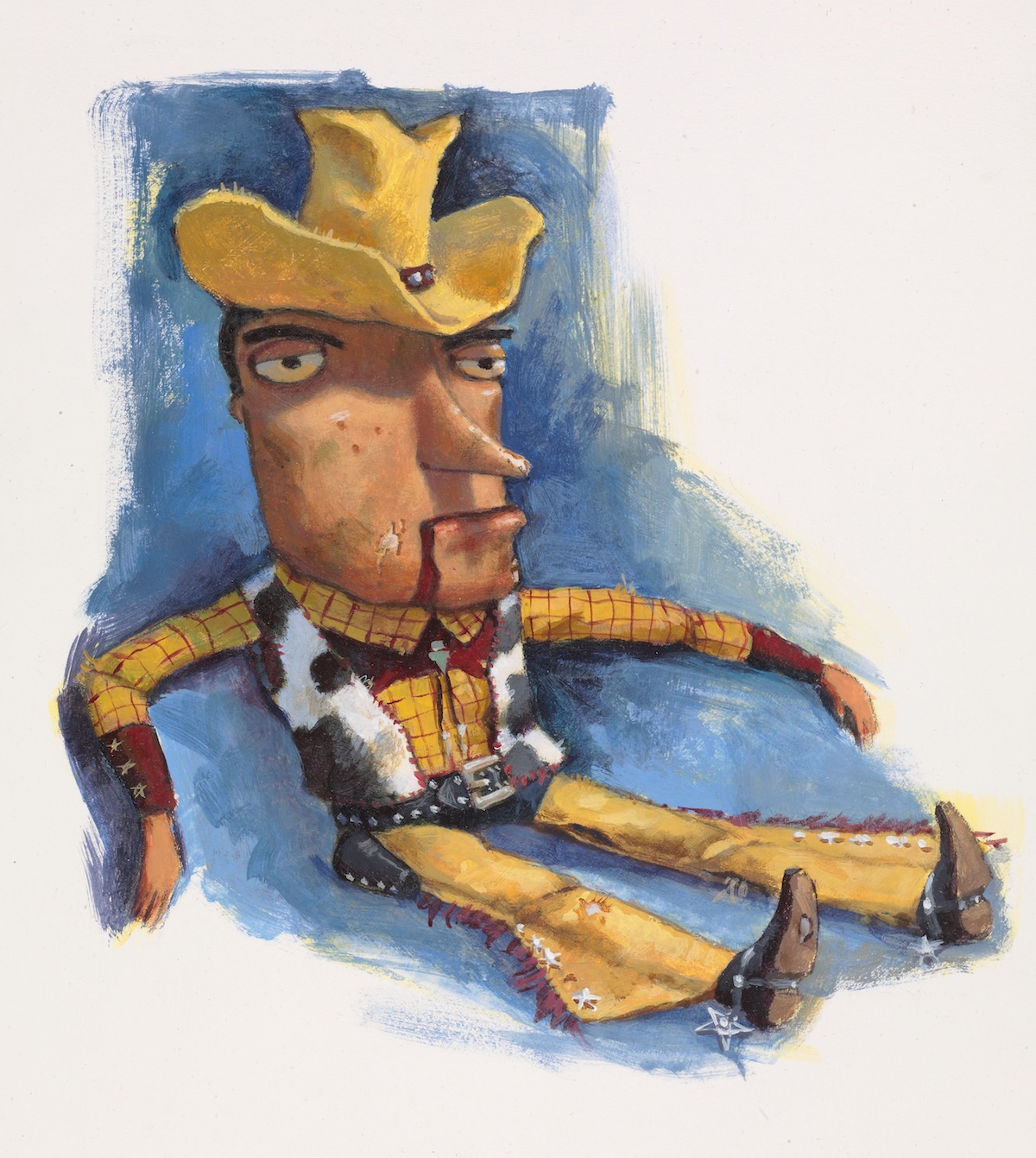

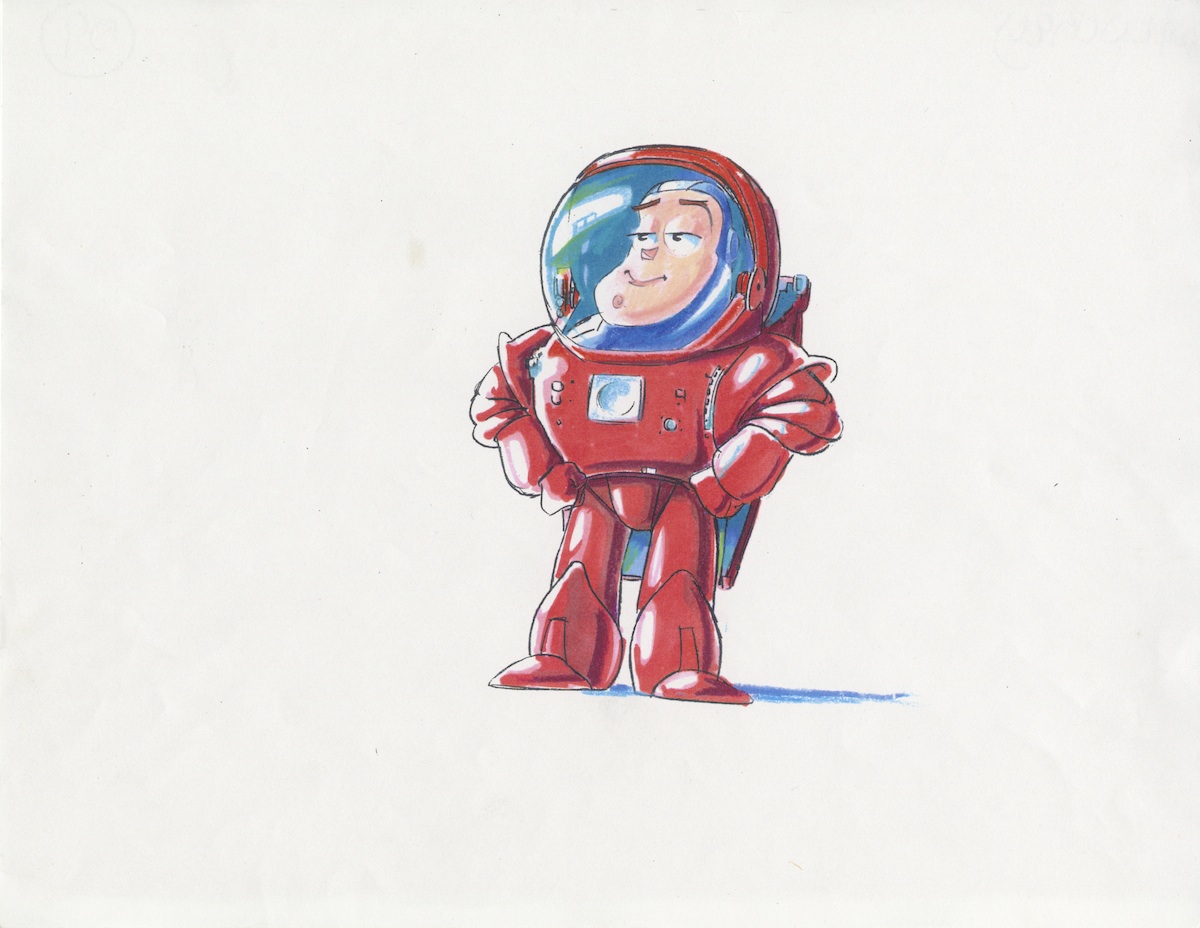

See Original Toy Story Concept Art for Buzz and Woody

The Story

That could very well have been the Pixar process, great technology powering their priorities. But even as the Pixar team leaned on the technology’s strengths, they had a cautionary tale from Disney history to keep in mind. Catmull says that he found that after Walt Disney’s death in 1966, the movies suffered when they prioritized art over story. And movies that live and die by technology can often suffer in retrospect, as those state-of-the-art special effects aged.

The problem is that, as Andrew Stanton puts it, “it’s not a widget you’re making. It’s not a product.”

Stanton says that once the team received the green light for the movie, they looked back at films that had staying power even after their outdated technology left the “strings showing,” such as Snow White, The Wizard of Oz and Star Wars. “We said anything that we break ground with, computer graphics-wise, will be subservient to getting the story right,” he adds, “because that’s what history has shown wins.”

So Stanton set about helping write the screenplay for a buddy movie, where the conversations would bring the characters to life as much as the unprecedented curves and planes. The writing team, which included Joss Whedon and Joel Cohen, paired the character concepts with a more cynical attitude than was typical for animated films, and Pixar also made the decision to skip musical numbers in favor of a more mature feel.

Disney balked at early versions of the story—Woody was not likeable enough, for example—and Catmull says the company “essentially shut down production” over the problem. The future “brain trust” shut themselves in a room to rethink the story. Stanton remembers telling Pete Docter at one point that the two main characters had to be engaging enough that people would think Buzz and Woody stuck in an elevator for 70 minutes was the highest quality of entertainment.

These days, it may sound obvious to say that part of Pixar’s success has been the appeal and emotion of the stories the studio tells—but 20 years ago, that didn’t necessarily have to be the case. Pixar’s contract with Disney had come as a result of its technological prowess, after all. The decision to put the story first was a key one, and it would power the next two decades of the company’s creativity.

Decades later, Stanton says that the “strings” do show, but the measure of the film’s success is that it doesn’t matter: “It’s the ugliest picture we will ever make, but you don’t care because you get wrapped up in the story to this day.” He remains so haunted by how well the movie turned out that he cannot watch the film more than once every two years or so, for fear of losing motivation on his current film projects.

To Infinity…

Children and adults flocked to theaters when Toy Story opened, making it the highest-selling film for three weeks in a row. As the first full-length, 3D computer-animated movie, it was a milestone for animation, possibly the most significant since the introduction of color.

But, many critics glossed over that achievement—which is exactly what the developers were hoping for. They were thrilled at the invisibility of the work, Catmull says.

Case in point: “Consider the new Disney animated feature, John Lasseter’s Toy Story, which is, incidentally, the first full-length film created wholly by computer and, not at all incidentally — by design, in fact — the year’s most inventive comedy,” Richard Corliss wrote in his Nov. 27 review for TIME that year.

The film won an Academy Award for Special Achievement, as well as nominations for Best Original Screenplay, Score and Song. Jobs told FORTUNE in Sept. 1995 that Pixar and Disney would break even if the movie was a “modest hit” at $75 million. It made over $361 million worldwide during its run.

Buzz and Woody’s story continued for two more films, with a fourth set for release in 2018. The foundation Toy Story set had effects far beyond the franchise. Pixar, which Disney acquired in 2006, has released 15 movies since then, accruing 26 Academy Awards and three Grammys in total. As the animators graduated from toys in a flat room to insects, monsters and fish, the studio’s abilities with technology advanced as well. The Incredibles was a milestone as a film based on computer-animated people. In The Good Dinosaur, opening this month, they’ll tackle prehistoric nature.

Lasseter says that for the past 20 years, the priorities established with Toy Story have continued to hold. Every story envisioned by the Pixar team requires something that they don’t know how to do, so they invent the technology that was needed. There have been more than 250 computer-animated films released worldwide since Toy Story. Lasseter attributes that plenitude in part to the choice made by the Toy Story team to worry about story more than showing off, and to concentrate on developing software to serve their ideas rather than the other way around: if Toy Story hadn’t succeeded the way it did, it might not have inspired others to follow.

As for himself, his metric for success doesn’t count animated movies made or Oscars won or tickets sold. It was just five days after the Toy Story premiere, as he changed planes in Dallas, that he knew the gamble had paid off.

“There was a little boy with his mom holding a Woody cowboy doll. The look on his face I will never forget. It was the first time I’d seen a character we created in the hands of somebody else,” he says. “I think about it every day: that character no longer belonged to me, it belonged to him.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Julia Zorthian at julia.zorthian@time.com