As I watched the horrific images from Paris flicker across my television screen last Friday, I found myself sickened by the loss of so much life and moved by the international displays of solidarity with France. An image of the Brandenburg Gate bathed in the tricolors of the French flag brought to mind one historic moment that will likely come up again in the aftermath of the attacks: the Munich Conference.

The day Neville Chamberlain and his French counterpart, Edouard Daladier, signed the Munich Agreement, Sept. 30, 1938, is perhaps the most emblematic moment of what poet W. H. Auden called a “low, dishonest decade.” Under the terms of the agreement, Adolf Hitler, who had already reclaimed the Rhineland and annexed Austria, would be allowed to add the German-speaking region of Czechoslovakia to his empire, in return for nothing more consequential than a promise that this would be his last territorial demand. A year later, when Germany invaded Poland, the British public realized that they should have listened to Winston Churchill, who, at the time of Munich, had warned that appeasing Hitler would only embolden him to make ever more unreasonable demands.

For the past 65 years, American presidents have regularly evoked this “Munich lesson”—that evil appeased is evil emboldened. Harry Truman initiated the trend in 1950 when he defended American intervention in the Korean war by drawing parallels between the way “Communism was acting in Korea” and the way “Hitler had acted ten, fifteen, twenty years earlier.’’ When Lyndon Johnson was asked why we were in Vietnam, he is alleged to have said he didn’t want to be “no Chamberlain umbrella man.” The Bushes, father and son, also cast their wars in the Munich mold. “If history teaches us anything,“ George H. W. Bush said, during Operation Desert Storm, “it is that appeasement doesn’t work. ” Twelve years later, George W. Bush echoed his father’s warning. “I will not wait on events,” Bush said, during the run-up to Operation Iraqi Freedom. “I will not stand by as the peril grows closer and closer.”

George Kennan, a veteran diplomat who lived long enough to hear a half dozen presidents cite the Munich lesson, was once asked if he thought Americans had drawn the correct conclusions from the lesson. Kennan said no. “No episode, perhaps in modern history, “ has been more misleading than the Munich Conference.”

If anything, Kennan was understating the case.

There is a growing academic consensus that Munich represented the diplomatic equivalent of a Black Swan event, a near singularity that has little to say about anything except itself. Dr. Jeffrey Record, who teaches strategy at the Air War College in Montgomery, Alabama and is the author of several papers on Munich and its postwar legacy, believes that three things made the historical moment unique: the scale of Hitler’s ambitions, his military machine and the man himself. It is a fantasy to imagine that, had Churchill rather than Chamberlain been sitting across the table at Munich, Hitler would have been deterred. Unafraid of war and boundlessly ambitious, Hitler was that most dangerous of leaders, a man who is neither appeased nor deterred by threats of force.

There are important parallels between the Munich Treaty and last week’s events in Paris. Over the last 18 months, ISIS has been evolving into a Black Swan. Already, it has acquired two of the three criteria that define such a threat: it has huge territorial ambitions and it is unappeasable and undeterrable. Promised a martyr’s reward in Heaven, over the past few weeks ISIS operatives have blown up a Russian airliner, launched suicide attacks in Beirut, killed at least 132 people in Paris and wounded hundreds. ISIS currently lacks the third defining factor of a Black Swan: military capacity, though time and technology are working to correct this deficiency.

So how should America, France and other nations respond to the ISIS threat? Vassar political scientist Stephen Rock, who, like Dr. Record, is an expert on Black Swans, believes the Paris attack demands a military response, but he cautions that an all-out attack on ISIS’s homeland in Syria and Iraq would probably backfire. Within minutes of the attack, images of dead woman and children would likely be flickering across iPhone and television screens from Borneo to Aberdeen, and within days of the attack, hundreds of would-be jihadis in Bristol, Belguim, Berlin, Amsterdam and Antwerp would likely be packing their bags for Syria.

The solution that makes most sense is not putting American boots on the ground—from our experiences in Iran, Iraq, and Vietnam, we know where that leads—but, rather, negotiating an end to the Syrian war. To a large extent, ISIS is a product of that war and continues to rely on it for recruiting, revenue and prestige in the Muslim world.

A settlement will require the cooperation of the seven major players in war—the U. S., Britain, France, Iran, Russia and the Bashar al-Assad government. The first three players don’t think much of the last three and vice versa, but as the Iran agreement demonstrated, when mutual interests are on the table, even enemies can find ways to cooperate. For all our sakes, let us hope the negotiators adopt the Iran model again. Otherwise, at some point, we may find that ISIS has graduated from causing murder and mayhem in our cities to vaporizing them. Hitler, after all, took a similar path—going from escalation to escalation, until 60 million people were dead and the entire European continent was in ruins.

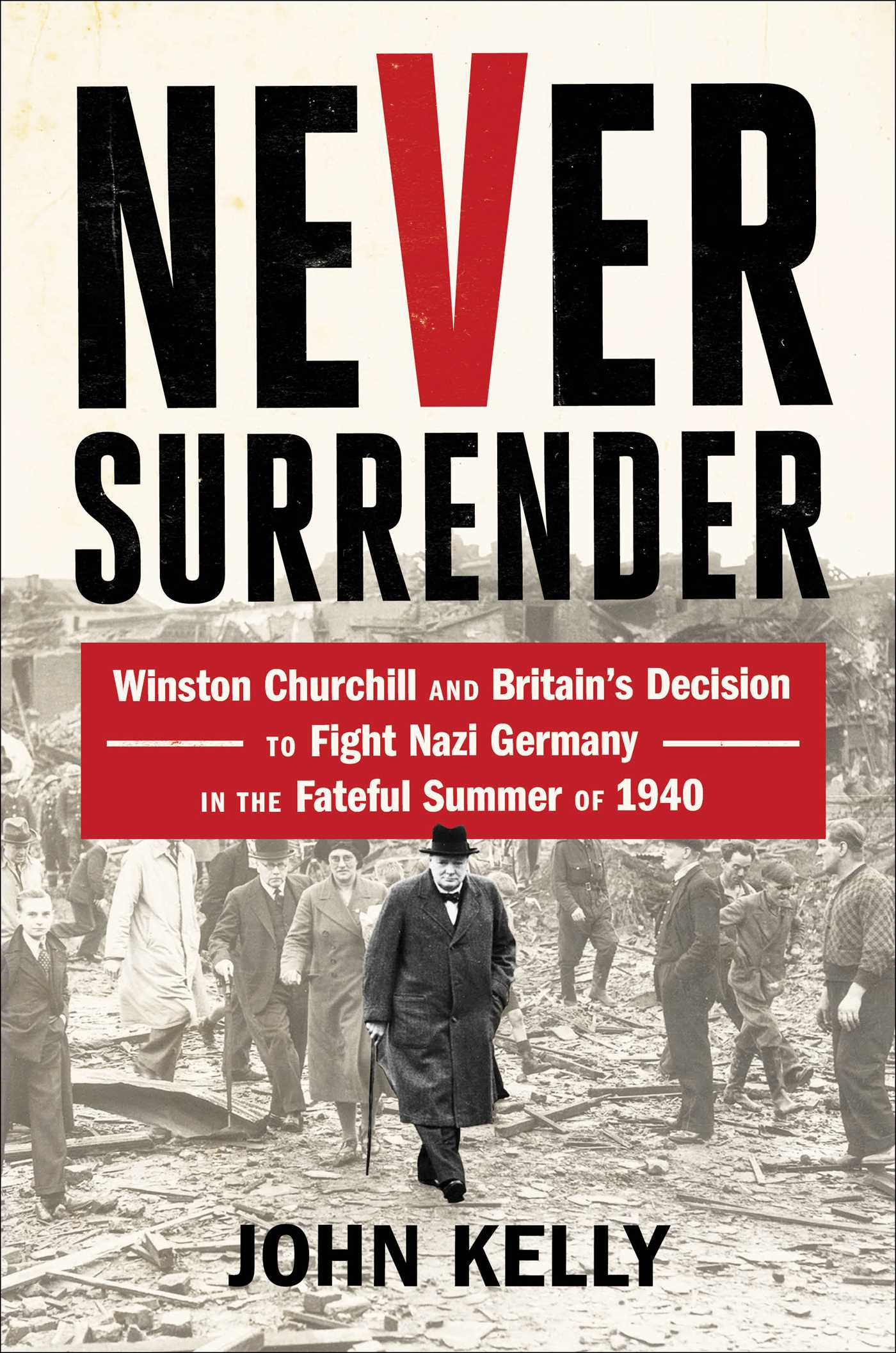

John Kelly is the author of Never Surrender: Winston Churchill and Britain’s Decision to Fight Nazi Germany in the Fateful Summer of 1940.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com