On Thursday evening, Hassan Mansour was working in the men’s clothing store he manages in the southern Beirut neighborhood of Burj el-Barajneh. It had been an ordinary night on this crowded, shop-lined street.

Then came the roar of an explosion. Mansour, 42, guessed the sound was a propane tank or a tire exploding. This wasn’t the 1980s, after all—Beirut was no longer a place where bombings where common. But he soon heard screaming in the street outside, then the sound of a second blast. “We thought we were under bombardment, like missiles landing on us,” he said.

The reality was that two men with explosives strapped to their bodies had blown themselves up, killing at least 43 people. At least one of the men’s vests was also packed with ball bearings that became lethal projectiles, tearing flesh, shattering shop windows and injuring at least 239 people. Metal balls were still lodged in the walls of some shops on Tuesday.

The double suicide bombing was one of in a chain of ambitious attacks on civilians in several countries claimed by the Islamic State of Iraq and Greater Syria (ISIS) over the past few weeks. ISIS also claimed the downing of a Russian passenger jet in Egypt on October 31 and took credit for the catastrophic attack in Paris last Friday.

Together those attacks demonstrate a shift in the group’s overall approach. ISIS’s hallmark has been its ability to maintain control over a vast swath of territory in Syria and Iraq—its Caliphate—and a smaller enclave in Libya. Now it is becoming increasingly clear that ISIS also seeks attacks that inflict massive civilian casualties far outside the organization’s territorial base.

That’s worrying for Western countries like France and the U.S., which ISIS threatened to attack in a propaganda video released on Monday. But in the future, it is Syria’s neighbors—where ISIS enjoys relatively easy access and the ability to cause massive havoc—that are likely to experience the brunt of those attacks. In Lebanon—which endured a bloody civil war through the 1980s that left the city in ruins—security forces, political factions, and ordinary people are bracing for more. “This could happen again,” said Zoheir Jalloul, the mayor of the Burj al-Barajneh municipality, in an interview near the blast site on Tuesday. “No president in the world, from Obama on down, can say, ‘I guarantee security 100 percent.’”

ISIS—a group largely composed of Sunni Muslims—proclaimed a sectarian motive in its statement taking credit for the Beirut bombing, stating that it intended to kill Shia Muslims. The statement also mentioned that it targeted Lebanon’s Hezbollah, the powerful, Iran-backed Shi’ite armed group that is fighting alongside the regime of Syrian President Bashar Assad in the country’s ongoing civil war.

While Hezbollah has clear influence in Bourj el-Barajneh, the residents of the neighborhood are far from uniform, including Palestinians, Syrians, and Egyptians, among others. The area also encompasses a Palestinian refugee camp. Among the victims of the bombing was a nurse at the American University of Beirut teaching hospital. Also killed were three residents of Dearborn, Michigan, including, Leila Taleb, a mother who had returned to Lebanon in hopes of bringing her family to the U.S. Another man, Adel Tormous, tackled the second bomber, preventing more people from dying while sacrificing himself.

For residents of the area, the bombing pierced what had been a unremarkable Thursday morning. Mansour, the clothing store manager, had rushed out onto the street after the explosions, trying to put out fires with an extinguisher from his shop. A gregarious man with wide eyes and a closely cropped beard, in an interview on Tuesday Mansour pulled out a smartphone to show a video he shot of the aftermath. In the footage, stunned survivors wander through the smoke and debris. Throughout is the sound of men and women shrieking.

Mansour said he began helping injured people into his shop, laying them out on the floor, next to the racks of shirts and stacks of Nike boxes until ambulances and motorbikes arrived to take them to a nearby hospital. Like others interviewed in the neighborhood, Mansour fears more attacks. “It’s not over yet. When it’s over in Syria it’ll be over here,” he said. “The whole world, including France and America, should unite against these criminals. They have no religion. They’re giving Islam a bad image. We support the people who were killed in France.”

Down the street, Abu Mohamed, 29, a Syrian shopkeeper who declined to give his real name for fear of reprisal, said that before the attacks, he had closed up his store, which sells toys, stationary, perfume, and other assorted items. After a moment, he realized he had forgotten important papers and returned inside the shop. As he bent over to retrieve for the files underneath his desk, the second bomber detonated his payload on the street outside. He was spared only because a metal box containing phone wiring blocked the shrapnel. In shock, Abu Mohamed ran home. He said he didn’t return to his devastated shop for three days, even though looters stole much of the merchandise.

Abu Mohamed has lived in Lebanon for about 10 years, but he said Thursday night’s bombing triggered a backlash against Syrians who were already enduring discrimination in Lebanon, where over 1 million Syrian refugees are living. The security forces reportedly arrested five Syrians and one Palestinian in connection with the bombing. “They beat up a lot of Syrians around here,” he said. “The reason no one messes with me is that the neighbors know me.”

Following’s Hezbollah’s entrance into the Syrian civil war, a series of bombings took place in Beirut’s southern suburbs, known as Dahiyeh, which are associated with the armed group. In past statements claiming credit for those those bombings, al-Qaeda affiliated groups have said that they were acting in revenge for Hezbollah’s actions in Syria. But now Lebanon must face the challenge of tackling future ISIS attacks in an atmosphere of deep political dysfunction. The country’s parliament has failed to elect a president for the last year and a half, and last summer the government faced protests over a long-running failure to even collect garbage in from the streets.

Aram Nerguizian, a senior fellow at the Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington, said a key question will be the future of Hezbollah’s role in Lebanon’s internal security and the group’s relationship with the Lebanese security forces. “The big issue is Hezbollah. Because they haven’t relinquished control of the internal security politics of some of the areas in Beirut, when you do have a major incident, its their credibility that takes the first hit,” he said in a phone interview.

While the security challenges are daunting, Lebanon’s chronically divided political factions have actually found a point of unity in their opposition to ISIS and its brutality. Imad Salamey, a political scientist at the Lebanese American University, said that Lebanon’s political factions are sensitive to the risk of polarization following the bombing. “The general mood, especially on a political level, is to avoid blaming, to avoid statements that would deepen division in favor of expressing the importance of confronting terrorism and Islamist radicalism from ISIS,” he said. “Everyone is aware. The stakes are extremely high.”

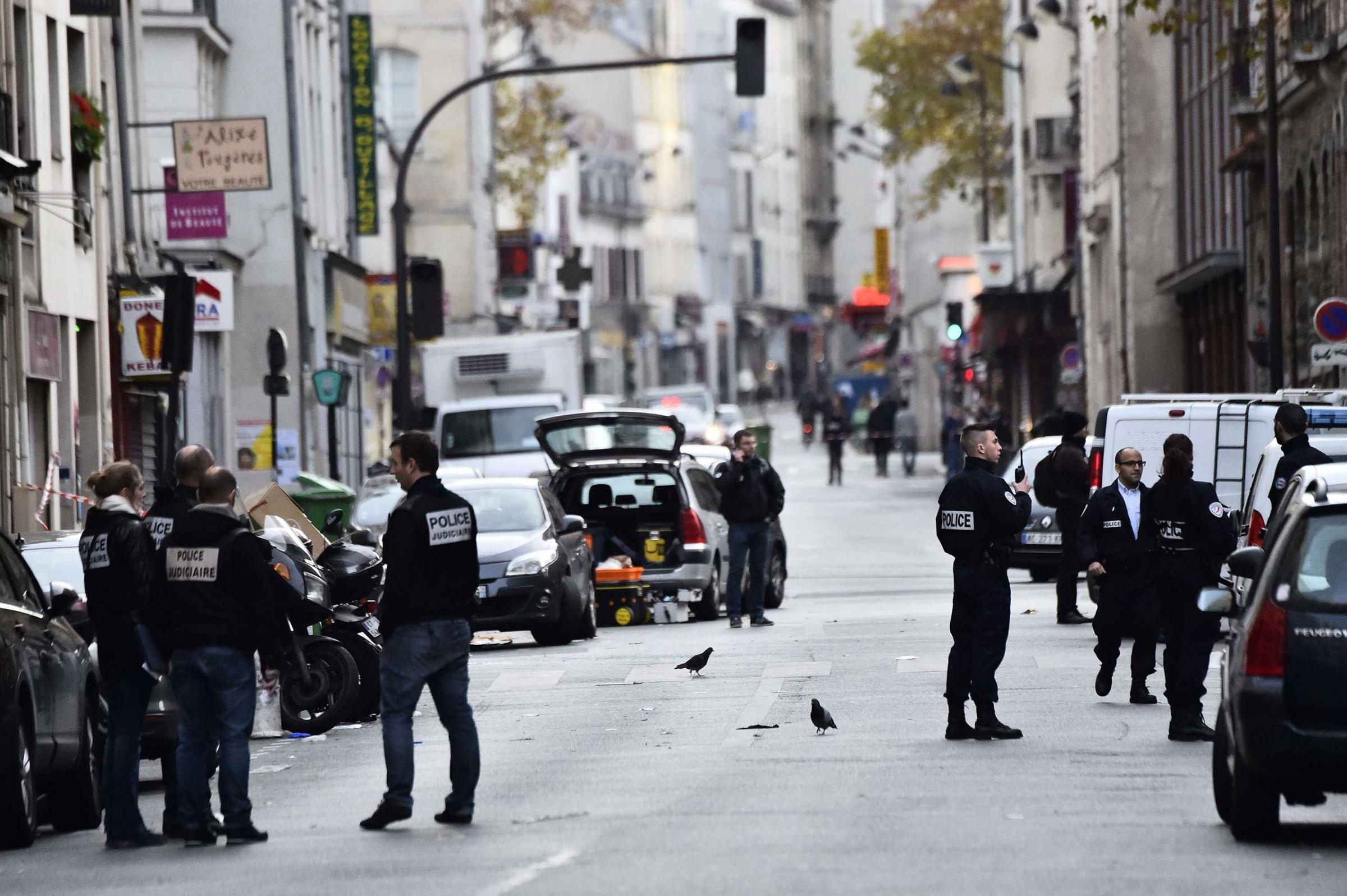

Witness Paris Mourn the Day After Deadly Attacks

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Introducing the 2024 TIME100 Next

- The Reinvention of J.D. Vance

- How to Survive Election Season Without Losing Your Mind

- Welcome to the Golden Age of Scams

- Did the Pandemic Break Our Brains?

- The Many Lives of Jack Antonoff

- 33 True Crime Documentaries That Shaped the Genre

- Why Gut Health Issues Are More Common in Women

Contact us at letters@time.com