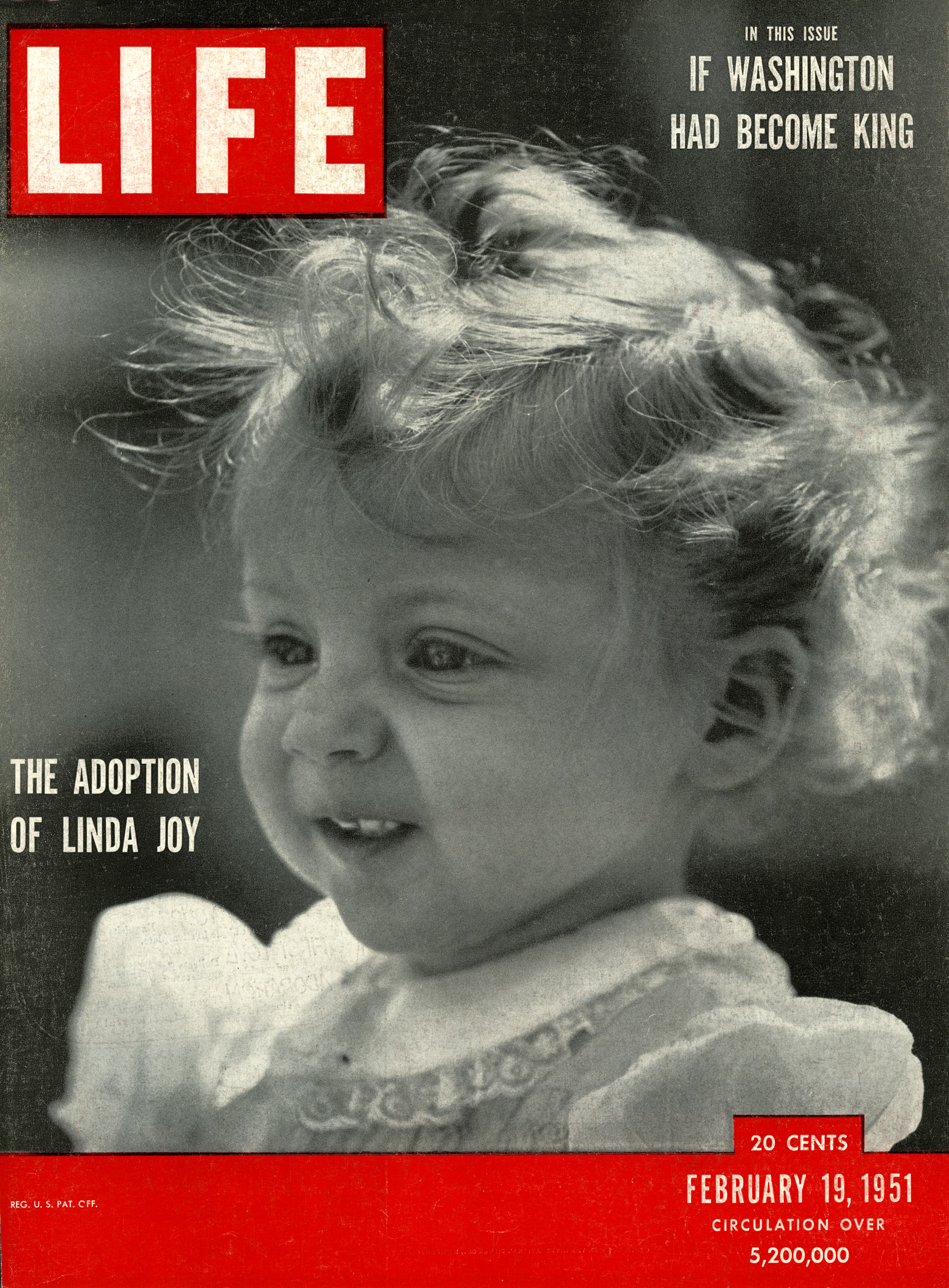

When Linda Joy Young was adopted in 1950 by Bernice and Robert Linville (“Lindy”) Young in Pasadena, Calif., LIFE magazine reported that while a million couples sought to adopt a child, only 75,000 babies were in need of a home. This disparity led to the rise of a black market, through which “so-called black marketeers” would charge as much as $5,000—nearly $50,000 in today’s dollars—to match a child with a family.

Since then, the numbers have shifted drastically in the opposite direction, and National Adoption Day, which has taken place on the Saturday before Thanksgiving since 2000, aims to close the gap. According to its organizers, more than 100,000 foster children are currently awaiting adoption, with an average wait time of four years and thousands more children aging out of the system. Since its inception, the annual day has helped finalize adoptions for more than 50,000 of those children.

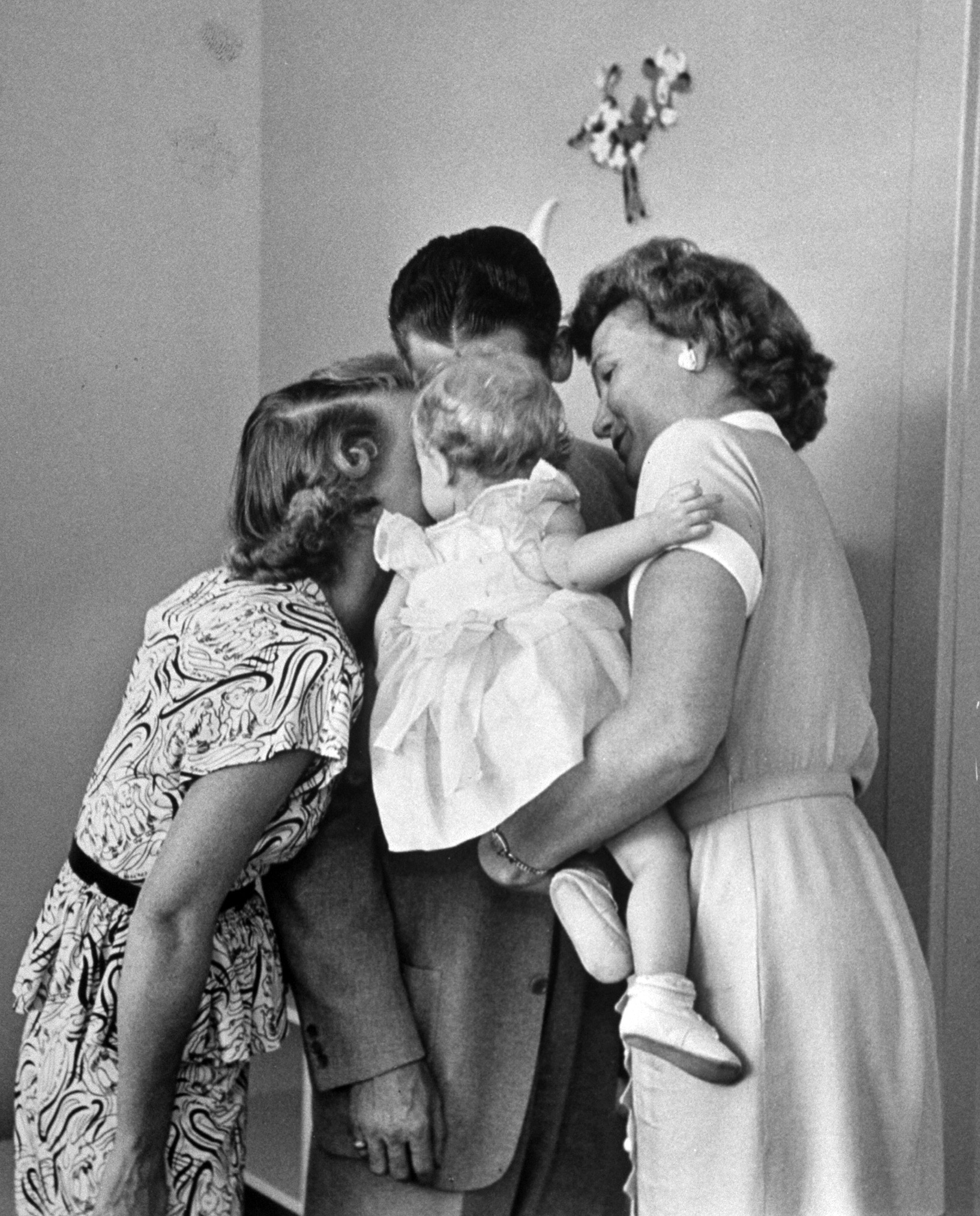

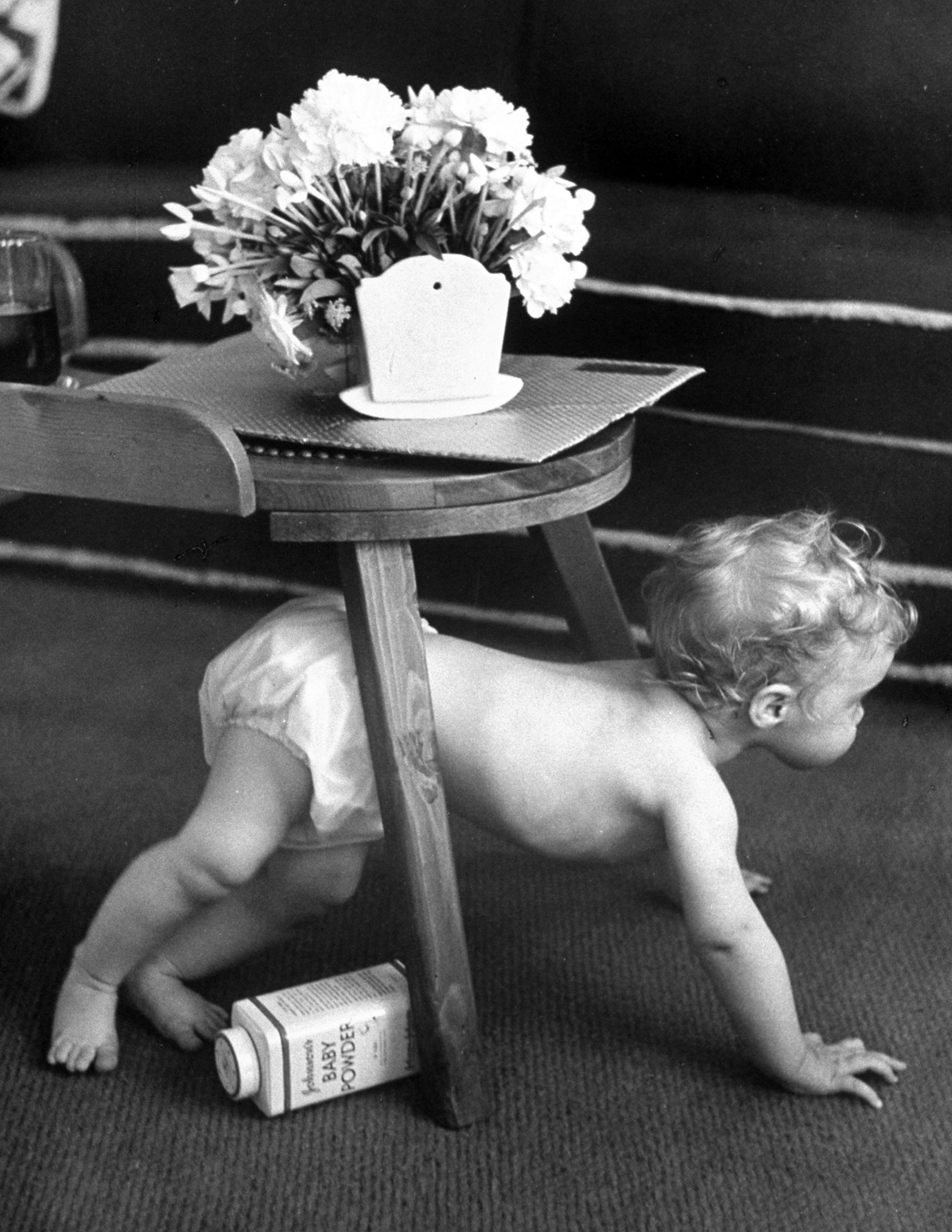

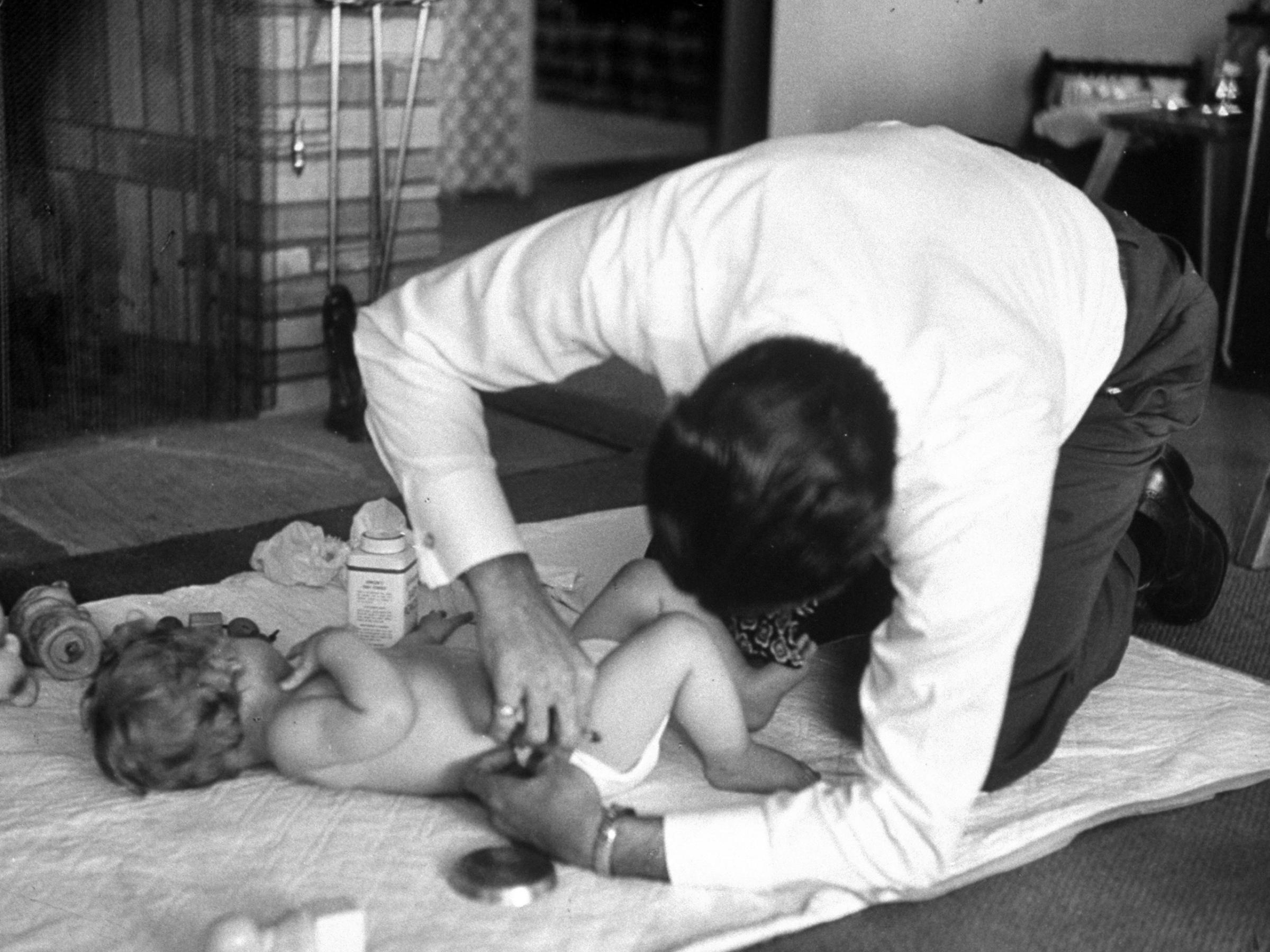

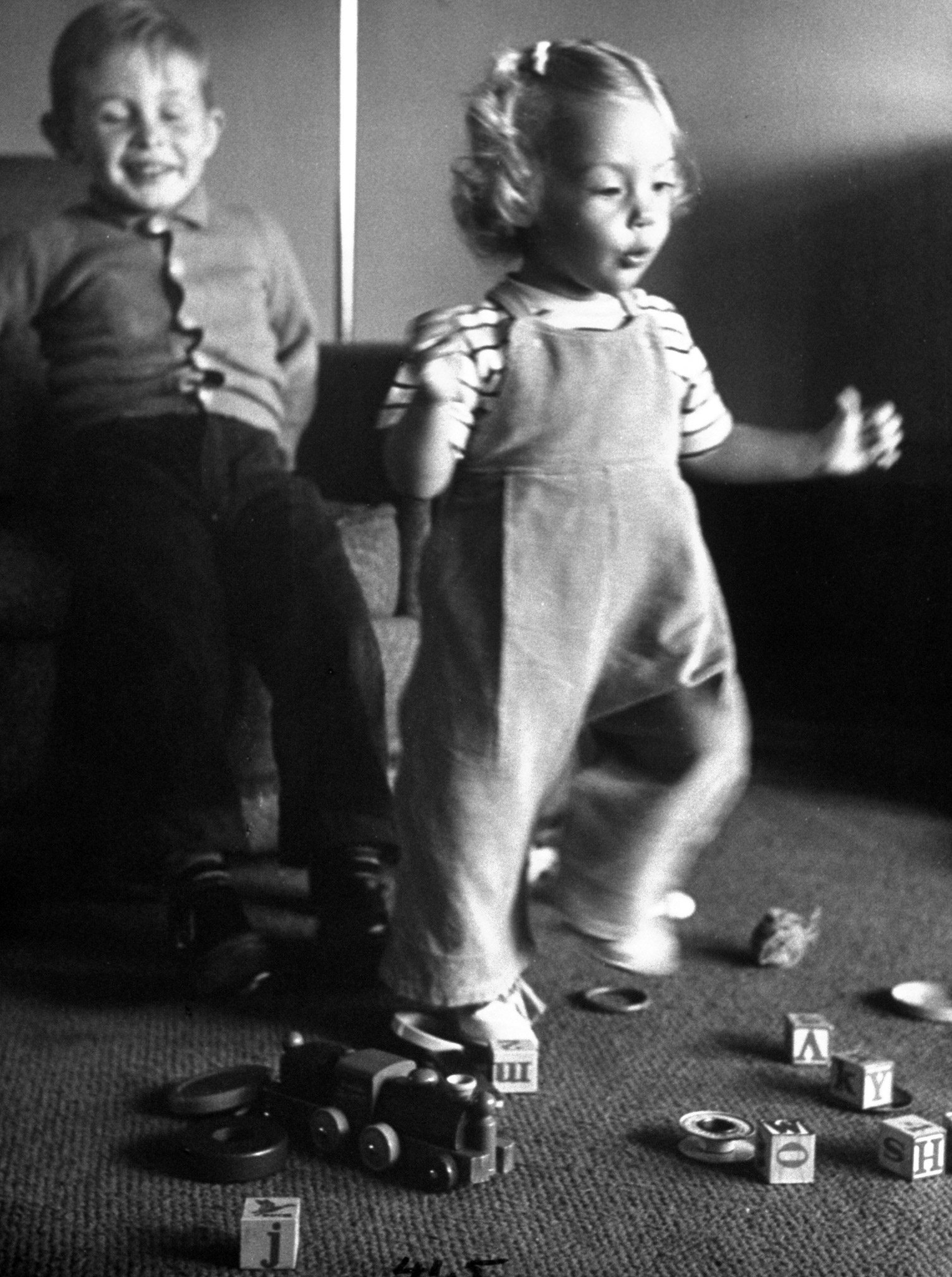

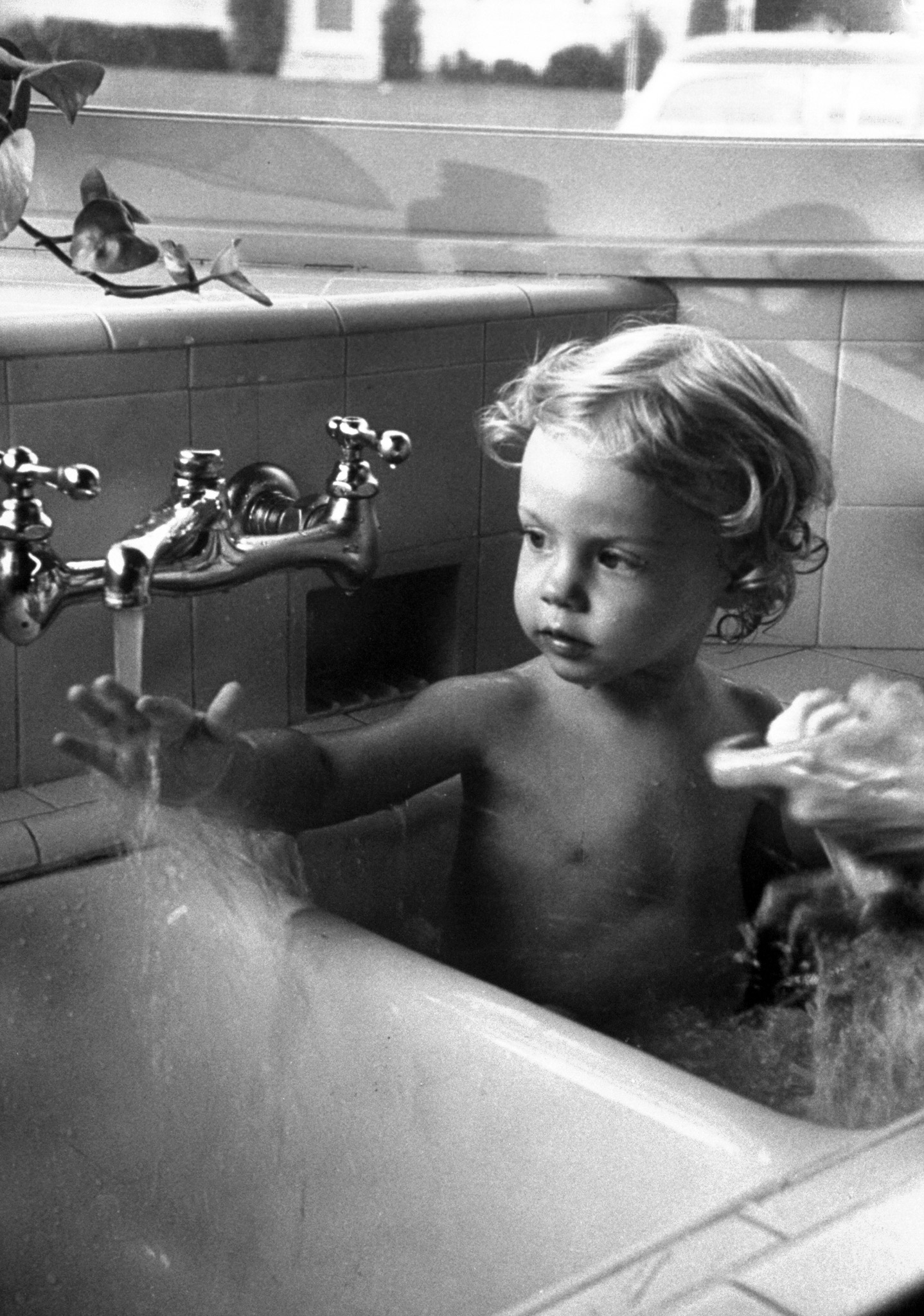

But back in the day when it was the prospective parents, and not the children, who endured long waits for a match, the process suffered from oft-ignored regulations. Only about half of adopted children were placed through authorized agencies, like Linda Joy was through the Children’s Home Society of California. LIFE published a tender photo essay by photographer Ed Clark—which captured the joy of both Linda and her parents as they got to know one another during her first days at home—with the hope that more stringent regulations might “eliminate the worst perils of adoption.” Indeed—coincidentally or not—beginning in 1951, the number of unauthorized adoptions began a period of sharp decline.

Linda’s adoption seems to represent the best case scenario for a child who needed a home and a couple who yearned to be parents. Still, this being 1950, the way LIFE describes the process might raise eyebrows among modern readers. As a prerequisite for the adoption, a caseworker “took a look at Bernice’s housekeeping” and “requested a medical report certifying their inability to have a child of their own.” Linda was put through a battery of medical tests to ensure that she was healthy—there is no explanation of how a finding of poor health might have affected the outcome of the adoption.

Sadly, Linda’s happy days with the Youngs were short-lived. Though she appeared healthy before the adoption, she was diagnosed with leukemia shortly after coming home and died just months after joining her new family. The Youngs later adopted a boy named Robert who, LIFE reported in a follow-up story, “may not understand for many years the double measure of love in his father’s hug and his mother’s smile.”

Today, of course, some of the same issues that plagued adoption more than six decades ago endure—cases of illegal adoption and child trafficking continue to be reported—and new disputes, such as legal challenges to adoptions of children by gay and lesbian parents, hamper the placement of children in need. While countless adoptions take place without complication, there are always stories about legal risks for prospective parents or parents who are ill-equipped to raise the children they are matched with. Still, as National Adoption Day highlights, one of the biggest obstacles to adoption in the U.S. today comes down to a game of numbers: Simply put, more mothers and fathers are needed.

Liz Ronk, who edited this gallery, is the Photo Editor for LIFE.com. Follow her on Twitter @lizabethronk.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Inside Elon Musk’s War on Washington

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Cecily Strong on Goober the Clown

- Column: The Rise of America’s Broligarchy

Write to Eliza Berman at eliza.berman@time.com