After a night of terror and chaos, Parisians found themselves caught between wishing life could go on as normal and fear that the bloodshed was not yet over. The City of Lights ground to a virtual standstill, with the authorities closing schools, museums, libraries, food markets, swimming pools and leisure centers. Security was boosted at city halls across Paris. Sports matches were canceled, many metro lines were shut and Disneyland Paris closed its doors for the first time since it opened in 1992, as the city reeled from the deadliest attack since World War II.

But in the 10th arrondissement, where two of the attacks took place, many cafés and shops were open on Saturday. Dozens of people wandered the streets, their faces fixed in somber defiance of the authorities’ instructions to stay inside for now. It’s a feeling I can understand. I had not been dispatched to Paris on assignment as a journalist. I had come for a weekend away with four friends, and spent Friday wandering cobbled streets in the Marais, eating crepes, sipping coffee and visiting museums.

When the first explosions went off on Friday night, I wasn’t looking at my phone. As we emerged from the metro about a quarter past ten and walked towards the restaurant where we planned to celebrate our friend’s birthday, it was immediately clear that the mood had shifted in the twenty minutes we had spent underground. Paris was not bustling with Friday night revelers but with tense clusters of people on the streets. I glanced at my phone, disoriented, and saw that there were reports of some kind of soccer-related violence at the Stade de France. But the scenes in central Paris told a different story: sirens were wailing nearby and the same words kept echoing on the crowded streets: Charlie Hebdo.

We arrived at the restaurant we had booked for dinner to find it had pulled all its shutters down and looked closed. Paris was under attack, we were told. While the dozen people and staff still in the restaurant tried to carry on as normal, serving dishes and mixing cocktails, my phone began flashing relentlessly with messages flooding TIME’s breaking news chat room. In between courses and clinking glasses, the death toll kept climbing: 18 dead, then 26, then 60. One hundred hostages. Four attacks, then six. Facebook wanted to know if we were safe, sending out an alert I’d only seen people use before during earthquakes. French President François Hollande imposed a state of emergency for the second time since 1961 and required all people entering the country to show documentation. Even taxi-hailing app Uber urged everyone to stay inside.

I had written about terror many times before, but I had never felt it until last night. The apartment we had rented for the weekend was nearly an hour’s walk away from the restaurant. Worse still, it was in the 10th arrondissement, less than a mile from three of the sites we knew to be under attack. Every taxi we saw was occupied, the nearby hotels were full and our cellphones were all so close to being out of battery that we couldn’t effectively search the #PorteOuverte (#OpenDoor) hashtag to find somewhere safe to stay. Stuck in the restaurant, we had no choice but to try and act as though things were okay. After all, unlike so many others, we were safe. “What the terrorists want is for us to be afraid,” each one of us would say from time to time, as if we weren’t. By the time we found a taxi and left the restaurant, it was past 4am. The streets of Paris had emptied and 127 people were dead.

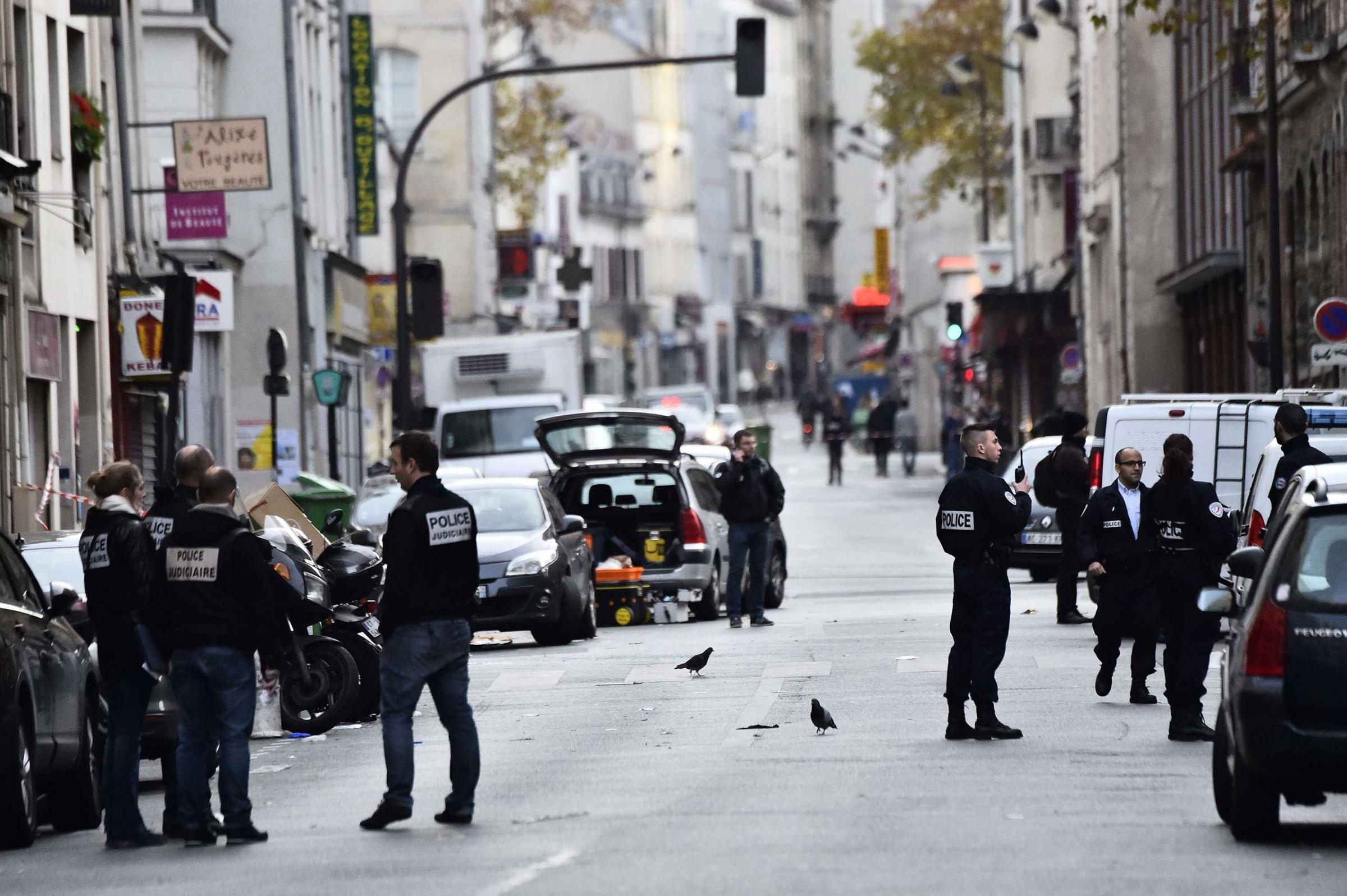

This morning, after a couple of hours of snatched sleep, I joined the crowds gathering at the corner of Rue Bichat to lay flowers and light candles outside Le Petit Cambodge restaurant and Le Carillon bar, where more than a dozen people were killed on Friday night. “I thought I was hearing fireworks,” sobbed one woman, hugging her neighbor. Opposite the bar and restaurant, a long line of people waited for more than two hours to donate blood at the medical center.

On the other side of town, at the Hôpital Universitaire de la Pitié-Salpêtrière, families of people injured in Friday’s attacks huddled together outside the emergency room. “We are still afraid, of course. Always. This is all the fault of President Hollande, he needs to get out of Syria,”” says Christophe, whose wife has just had an operation to remove the shrapnel in her leg after being injured in the explosion by a McDonalds near Stade du France. “I am desperate to see her, the doctors haven’t let me yet,” he says, his eyes filling with tears. Christophe, who asked TIME not to publish his last name, is of Serbian origin but was born and raised in Paris. Once his wife has recovered, he wants to move away with their four-year-old son. “France is a catastrophe.”

Fabien Leroi, 31, agrees that he would no longer feel comfortable bringing his three-month-old baby into central Paris, given what has happened. Leroi has come to visit his colleague, who was shot last night at the Bataclan. “The bullet just missed his liver,” says Leroi, who received news at 5am that his friend was in the hospital. “2015, it’s been a tough year for France.”

Witness Paris Mourn the Day After Deadly Attacks

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Naina Bajekal / Paris at naina.bajekal@time.com