Immediately upon entry into Marian Goodman’s North Gallery, one encounters a somber gray-framed black-and-white print titled Approach (2014). It measures 78 by 97 in., and it glimmers in silvery tones along a slightly darkened wall. It shows a middle-aged black woman wrapped in a blanket approaching a low-slung row of cardboard boxes stacked in the lee of a high wall under streetlights. A right foot protrudes outward from a gap in the boxes, beneath a tarpaulin sheet that doubles as a curtain. The woman peers steadily toward the shadowed recesses, within which a hidden person appears to sleep rough on the street.

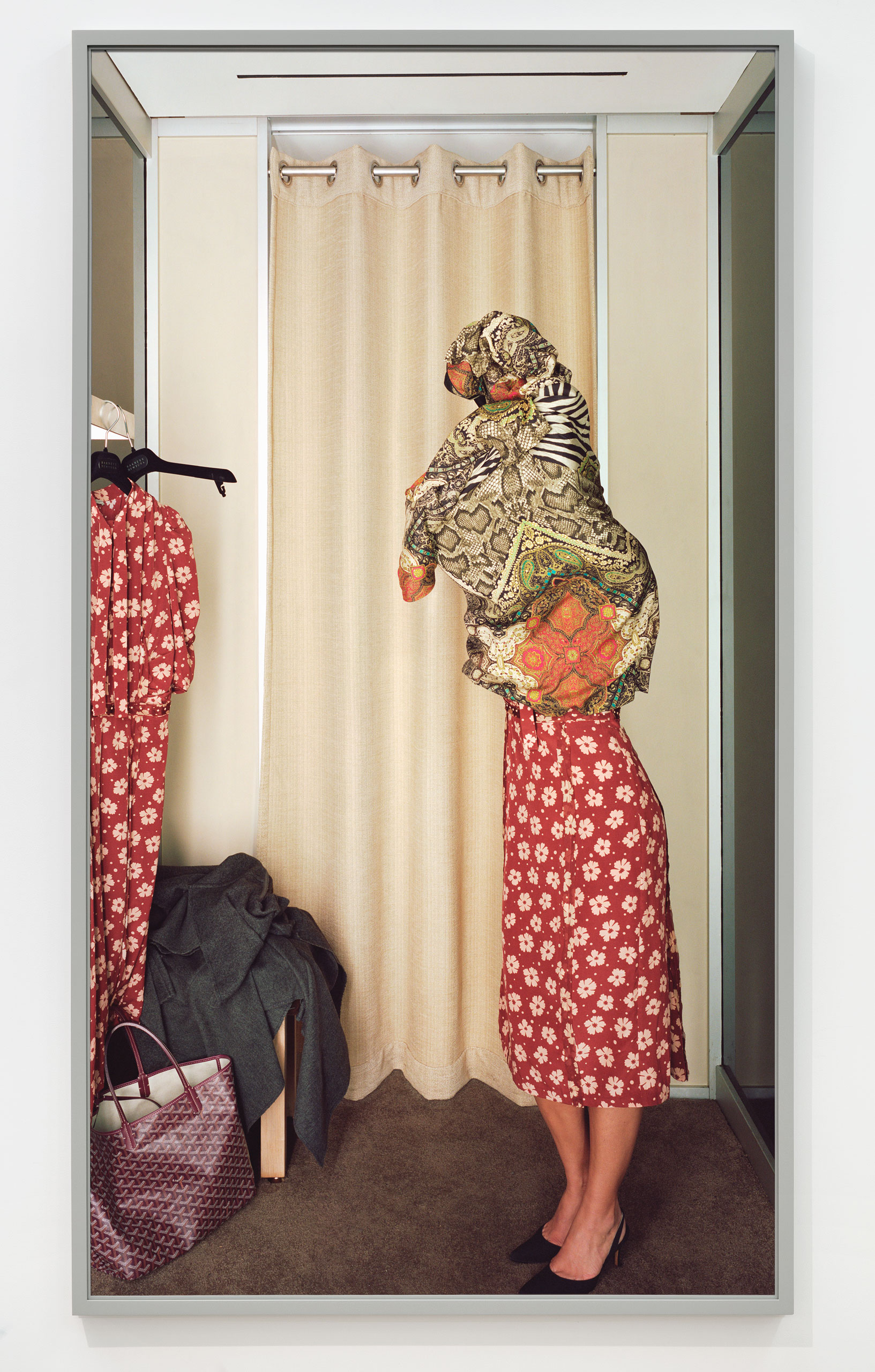

To the left of this photograph hangs Changing Room (2014), in which a woman stands behind a curtain in the narrow, brightly lit confines of a cubicle in Barney’s New York. She is struggling into a florid patterned dress that gradually engulfs the upper half of her body, its stunted silhouette making the shape of a budgerigar squatting atop her head. She seems to be concealing a second red dress beneath this first, and an identical red dress with a cream floral print hangs opposite her on a rail. A long gray woolen coat rests on a stool nearby, and she is hidden behind the cubicle’s curtain but revealed to the camera lens, whether caught in a moment of theft or retail therapy, the photograph itself does not confirm.

These two photographs form part of a measured and statuesque installation of eight works, seven of them new, in Jeff Wall’s latest solo show New Works, which opened in New York and London. They are emblematic of Wall’s large-scale, uncanny and ambiguous images, which have marked him out as a major artist since his earliest work in 1978. Wall’s photographs are arresting and immersive, detailed enough to sustain extended close readings, but large enough to hold the attention of a viewer many feet away.

Wall’s photographs have covered a spectrum of subject matters from otherworldly scenes (The Flooded Grave, 1998-2000) to random incidents (Boy Falls From Tree, 2010) to elaborately reconstructed images that incorporate references to other artists (Invisible Man by Ralph Ellison, The Prologue, 1999-2000). For more than 20 years, these photographs were printed onto transparencies mounted within light boxes, although Wall has since discontinued this practice in favor of equally large black-and-white, or digital color prints.

Throughout this period, Wall has created works that locate their action at the threshold between the self-evident and the nonsensical, seeking to enrich and expand our attention toward the specific properties of photographic experience. His gnomic titles and deceptively straightforward compositions combine to raise a multitude of questions, for which the recalcitrant stillness of a photograph can provide no conclusive answer.

In Staircase & two rooms (2014), a triptych of vertical photographs is arranged side-by-side like an irregular landscape in which a middle-aged man leans against the inside of a doorframe, the bulk of his body concealed by the opened door. His eyes seem to peer outward from his single frame toward the central panel of the staircase, beyond which a second man reclines along the verge of a double bed in the third image of the piece. We might presume that the first man listens with disquiet to the noise of the building, and that the central staircase separates him from the source of his distraction. But the second man in the final panel rests in a room with two doors, one of which is cracked slightly ajar, leaving open the possibility of an illicit tryst between two lovers separated by a triptych, but conceivably occupying adjoining rooms.

The photographs in New Works describe a variety of incidents that orbit around themes of domesticity, property, separateness, territory and identity. They comprise jarring conjunctions of sublimity and repression, as in Daybreak (2011), where a group of slumbering Bedouin are pictured during a radiant dawn at the foot of an olive grove in front of an Israeli prison. The pictures elicit instinctual assumptions that are complicated by subtle details, as in Approach, where the new sheen on the woman’s black flats belies the notion that she is homeless, just as her hesitancy complicates the presumption that she is familiar with the scene that she approaches.

Wall’s work demonstrates with eloquence and persistence that imagination is foundational to the reception of visual facts, or that seeing requires an often unstated act of faith. His works continue to mine the anonymous events that account for the vast majority of everyday life, showing us in whimsical and poetic ways that these can be both emphatic and elliptical, arresting and irreducible, simple and yet utterly strange.

Jeff Wall’s New Works is on show at the Marian Goodman Gallery in New York until Dec. 19, 2015.

Stanley Wolukau-Wanambwa is a photographer, writer and the editor of The Great Leap Sideways.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com