In 2008, Jetta Darrow cast her vote for Hillary Clinton in the New Hampshire Democratic primary. She worried that Barack Obama wasn’t experienced enough to be President, she thought Clinton had the right qualifications for the job, and the prospect of a woman in the White House excited her. But this time around, Darrow, a 63-year-old office administrator for a civil-engineering company, has changed her mind. Since 2008, she says, she has buried her husband — a Vietnam veteran — but received only a quarter of his pension, her health care costs have risen, and she hasn’t seen a pay raise. All while struggling to help take care of her sick 11-year-old grandson.

She doesn’t blame Obama or Clinton for her woes. But breaking “that highest, hardest glass ceiling” — as Clinton once described it — suddenly doesn’t seem as urgent as fighting for struggling families like hers. So she’s going with Bernie Sanders, the insurgent, self-identified socialist Senator from Vermont whose surprisingly strong challenge from Clinton’s left flank has bedeviled the front-runner for much of this year.

“He spoke exactly to my concerns, as if he were living in my house, or my neighbor’s house, or my sister’s house,” Darrow says as she spreads out snacks in the sunny kitchen of her Nashua home, which she shares with her daughter, son-in-law, grandson and a poodle mix named Sugar. “He is the most sincere candidate.”

As Clinton has rebounded from a sluggish summer thanks partly to a widely praised showing in the first Democratic debate, Darrow represents a tiny but intriguing slice of the electorate: post-middle-age, Democratic women who are supporting Sanders despite the possibility that Clinton may represent the best chance in their lifetimes to see a woman in the White House. Interviews with dozens of these women in recent weeks, mostly in New Hampshire but also in states from Pennsylvania to California, reveal a wide range of reasons for supporting Sanders over Clinton. Some reject the premise that Clinton is the only woman likely to reach the presidency in their lifetime, citing other possibilities like Elizabeth Warren, the Massachusetts Senator who decided not to run this year. Most take pains to say they are not rejecting Clinton, but are just excited by Sanders and his more liberal policy agenda. And almost all say the fact that Clinton is a woman simply doesn’t matter to them as much as they thought it would.

“It’s not about gender,” Darrow says. “It’s about empathy.”

None of this is to say Clinton has a problem with female Democratic voters. She doesn’t.

Clinton — who will face off with Sanders again in the second debate on Saturday — generally gets favorable ratings from about 80% of the demographic in national and early-state public-opinion polls. Her support among women has, for the most part, risen and fallen in ways that track her support with Democratic voters at large. Her debate performance and her steady testimony before a GOP-led congressional committee investigating the Benghazi attack has solidified her status as the Democratic front-runner, with large leads in national polls. (A New York Times/CBS News poll released Thursday shows her leading Bernie Sanders by 19 points nationally.) Other recent polls show Clinton erasing Sanders’ lead in New Hampshire, even gaining a small edge in the first-in-the-nation primary state where the Vermont Senator is strongest.

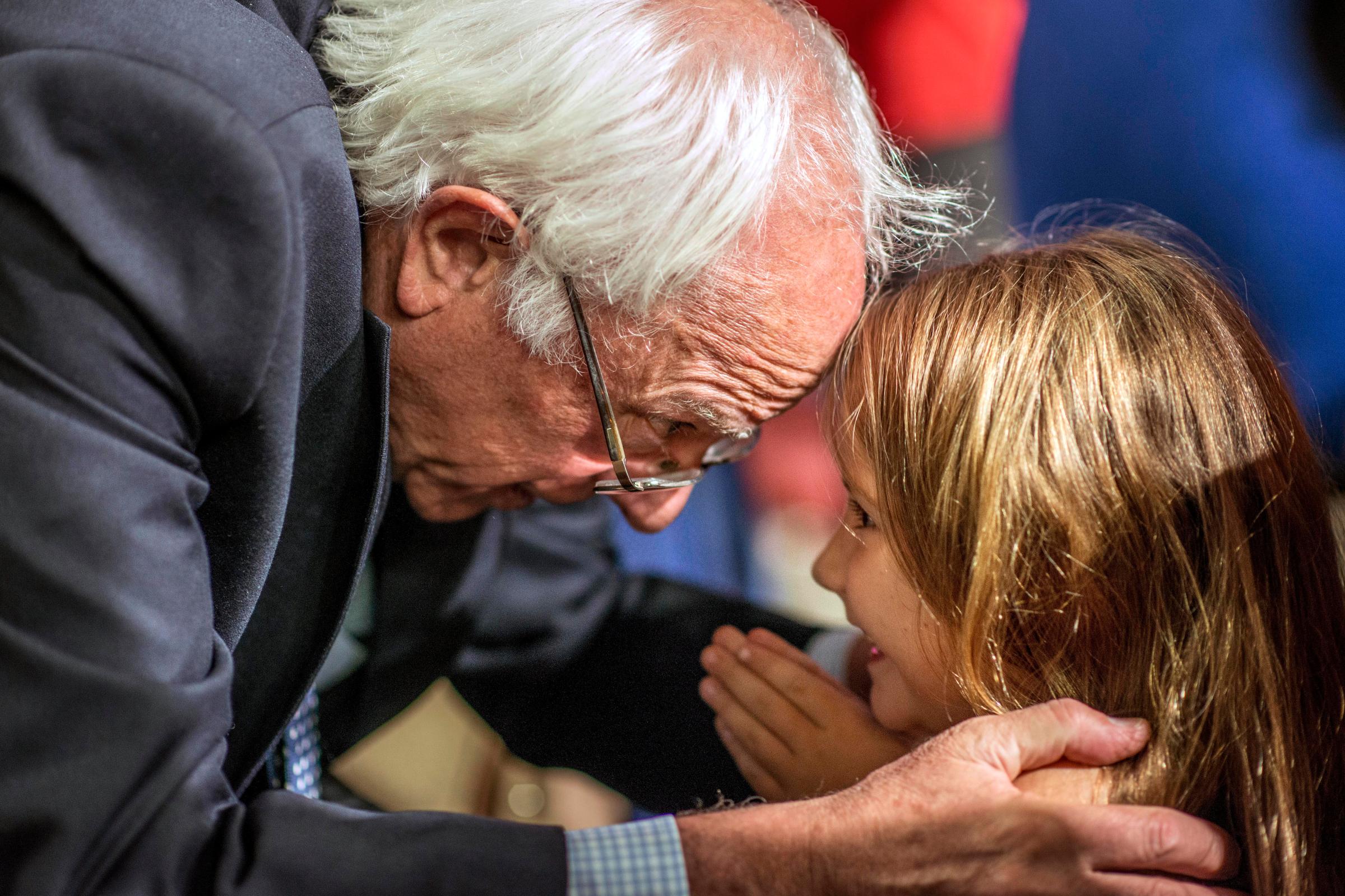

Almost nobody expects that women will abandon Clinton for Sanders in large numbers. But even though they’re in the minority, the women who support Bernie Sanders are important. Women’s votes could mean the difference between Sanders winning or losing New Hampshire; Clinton’s advantage among women is slightly smaller in the state than it is nationwide. And Sanders almost certainly needs a victory in New Hampshire to stay viable for the rest of the primary. That’s why he’s starting to move his campaign from large rallies to more intimate settings where he can target pro-Clinton constituencies like women and African Americans.

But female Sanders supporters also offer a glimpse into how some voters are weighing the historic nature of a female presidency against other political priorities. “The excitement of her being the first woman President is a little more muted than it was in 2008,” says Anna Greenberg, a Democratic strategist unaffiliated with any presidential campaign. “And that’s just because she’s been around.”

Determined not to let that excitement wane, Clinton is taking a different tack toward the historic nature of her campaign than she did in 2008. In that race, she largely avoided talking about her gender until victory was slipping away. This time, she’s making it a key calling card of her candidacy — a way to rally supporters, to separate herself from Obama, and to paint herself as something other than a political insider during a year when populist disaffection is rewarding outsiders. She has called for a country in which “there are no ceilings for anyone,” and “where a father can tell his daughter, ‘You can be anything you want to be, including the President of the United States of America.’” She routinely mentions her mother and granddaughter in campaign appearances, and images of little girls dressed up as Madame President litter her Instagram feed.

“Who can be more of an outsider than a woman President?” she said on the Today show last month.

The Clinton campaign doesn’t seem worried. Officials of course never expected she would get unanimous support from them; such an expectation, one adviser says, would be sexist in its own right. “It’s a double standard,” Clinton campaign pollster Joel Benenson says of “the assumption that a group of people based on gender, age, ethnicity, religion, ought to be on lockstep with a candidate.”

Even Clinton herself says women shouldn’t vote for a candidate merely because she’s a woman. “I’m always in favor of women running,” she told TIME in a recent interview when asked about the appeal of Republican presidential candidate Carly Fiorina, the only woman in the GOP field. “But people need to hold women’s policies up to light and determine what their answers to problems would be before deciding to support them.”

For some Sanders supporters in New Hampshire, that’s exactly their reasoning. “Hillary is that polyester pant-suited lady from the ’70s who lip-speaks feminism, but doesn’t grapple with the issue of poverty,” says Sylvia Gale, a 66-year-old former state legislator and Sanders volunteer. “The best feminist for the job is Bernie Sanders.”

‘There will be another Hillary Clinton’

Dudley Dudley is as surprised as anyone by her support for Sanders. The 79-year-old broke barriers in New Hampshire as one of few female lawmakers in the 1970s, and most of her friends are backing Clinton. “I expected to support her, until I heard Bernie Sanders speak,” she says over popovers at a café in Portsmouth, N.H. “I will work very hard for her if she gets the nomination, but I’m hoping that Bernie Sanders becomes President.” Dudley, who made headlines in New Hampshire when she prevented shipping magnate Aristotle Onassis from building an oil refinery off the coast in the 1970s, is from the generation that made the first push to get women elected to office in large numbers. Her unusual name — her first name plus her married last name — became her political tagline when she ran for Congress with the slogan “Dudley Dudley, Congress Congress” (she lost).

But even among some women of this barrier-breaking generation, the idea of seeing a female President doesn’t carry the urgency one might expect.

“Is it that important of a goal?” asks Darrow, the office administrator. “I know Hillary’s prowomen, but Bernie’s definitely prowomen. I just feel he’ll fight a little harder, he’s not beholden to anyone.”

And after the race barrier fell with Obama’s historic election, some think it’s only inevitable that the gender barrier will fall by the wayside, too — if not now, then next time.

“I don’t think of it as now-or-never,” says Dudley. “There will be another Elizabeth Warren, another Hillary Clinton.”

That might be wishful thinking for older women, Greenberg says. The Republican wave elections of 2010 and 2014 decimated a generation of rising Democratic politicians, leaving the party’s bench especially bare at the gubernatorial level, which is often a pipeline to the presidency (of 18 Democratic governors, three are women). Elizabeth Warren will be 75 on Election Day in 2024, well past Clinton (69 on Election Day) and Ronald Reagan (69 when he took office). And there are only a handful of Democratic women in the Senate who will be younger than 70 before the next presidential election. (Among them, New York’s Kirsten Gillibrand, 48, is seen by some as having a promising future on the national stage.)

If Clinton isn’t elected, the first female President could just as easily be a Republican, Greenberg says. “As someone who personally would like to see a woman President,” she says, “I’m a bird-in-hand person.”

Pro-Sanders, not anti-Clinton

For Dudley, Sanders’ positions on income inequality and money in politics are more important than any loyalty she might feel for a fellow woman politician. “It’s not anti, it’s pro,” she says. “I don’t really have anything bad to say about Hillary.”

The vast majority of female Sanders supporters agree with Dudley: they’re motivated by affection for Bernie Sanders, not aversion to Hillary Clinton.

But among some New Hampshire voters who see Sanders as an antidote to big-money politics, Clinton hatred runs high. Laura Thompson, a 57-year-old freelance writer who calls herself the “original feminazi,” says she resents the idea that all women should rally behind Hillary. “She assumes that we are her constituency. We are not,” Thompson says emphatically over coffee in Keene, N.H. Thompson, who volunteered for Sanders and says she gave him her first-ever campaign contribution, vowed to sit out the election if Clinton is the nominee.

Most Democratic women backing Sanders, however, say the stakes are too high to sit out a general election if Clinton ultimately is their nominee. “I’d have to hold my nose and vote for her,” says Dottie Oden, a 68-year-old retired teacher backing Sanders.

Morgan Dudley, Dudley’s daughter, says she thought she’d support Clinton — until she heard Sanders’ ideas on making college affordable. The younger Dudley, who is in her 50s and works in university development, is disappointed with what she sees as Clinton’s flip-flopping. But she says Clinton could win her over if she took an unpopular stance on a major issue: “That’s how you gain people’s trust — saying ‘I know this isn’t popular, but it’s the best thing for the country.’”

As she prepares for the second Democratic debate this weekend, Clinton can take comfort in the fact that most Democratic women don’t need convincing. “Hillary has been through everything,” says Jennifer Dollar, a 53-year-old Clinton supporter in Nashua, who sees the candidates’ battle scars and flexibility on policy as assets, not liabilities. “I fight for something, I call, I write letters, and then they change,” she says. “Am I going to attack that?”

And even the most enthusiastic female Sanders supporters say they were impressed by Clinton’s strength in the first debate and the congressional hearing before hostile Republican critics. Clinton, Darrow says, “handled herself with fantastic grace.”

“If she got the nomination,” Darrow says, “I’d be happy and hopeful.”

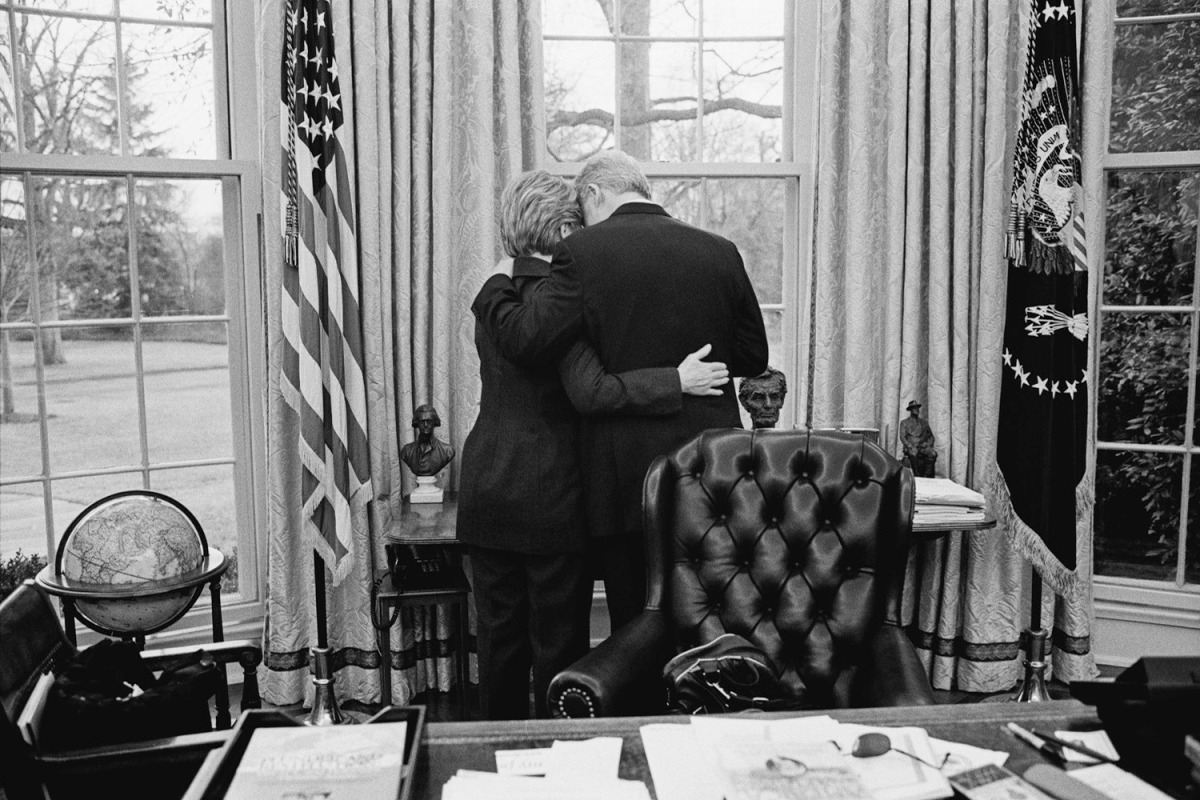

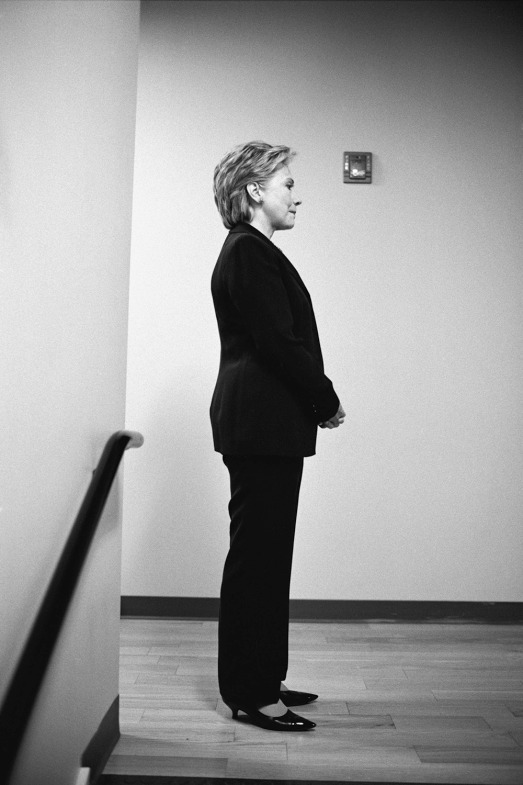

See an Intimate Portrait of Hillary Clinton

More Must-Reads from TIME

- How Donald Trump Won

- The Best Inventions of 2024

- Why Sleep Is the Key to Living Longer

- Robert Zemeckis Just Wants to Move You

- How to Break 8 Toxic Communication Habits

- Nicola Coughlan Bet on Herself—And Won

- Why Vinegar Is So Good for You

- Meet TIME's Newest Class of Next Generation Leaders

Write to Charlotte Alter / Nashua, N.H. at charlotte.alter@time.com