Many college graduates have a story of marching in the quad, or holding signs, or gathering to chant slogans in front of a university building. Protest is as much a part of college as late-night pizza or last-minute exam cramming. But some movements make change, while others die down when midterm season comes or leaders graduate.

Students at the University of Missouri found themselves in the former category on Monday, when their protests over the University of Missouri president’s handling of racial issues on campus led to his resignation. Students had been ramping up pressure against Tim Wolfe for weeks, arguing that he had ignored or minimized problems including racial slurs hurled at black students and a swastika drawn in feces on a campus wall. On Monday, as a graduate student’s hunger strike stretched into its eighth day, and the school’s football team threatened to go on strike (which could have cost the university $1 million), Wolfe announced that he would step down and students celebrated.

So why do some protests actually make a difference while other movements exist only as hazy memories? All successful student protests have two things in common: a tangible goal, and a specific strategy that appeals to the public beyond the university.

Here are three historic examples of students protesting and achieving meaningful change:

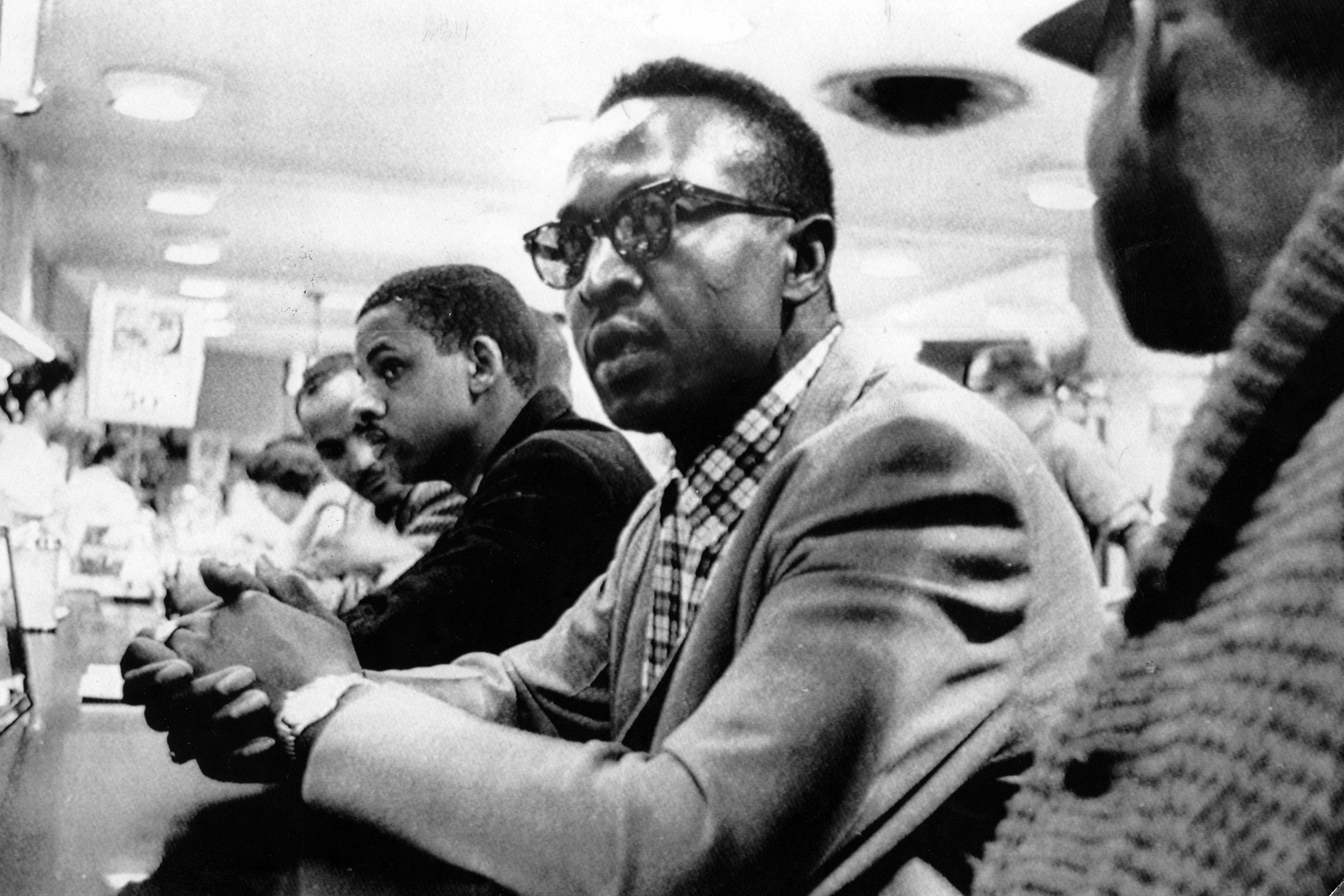

The Greensboro Lunch Counter Sit-Ins, 1960

The four young civil rights activists who staged the powerful sit-ins at a Woolworth lunch counter in Greensboro, N.C. were all students at North Carolina Agricultural and Technical College.

Their tangible goal: To force Woolworth to reverse its policy of racial segregation in its Southern locations.

Their specific strategies: On Feb. 1, 1960, Ezell Blair Jr., David Richmond, Franklin McCain and Joseph McNeil sat at the whites-only counter at Woolworth, and they refused to leave even after they were denied service and police arrived at the scene. Over the next several days, more than 300 other students came to peacefully sit and demand service at Woolworth, and the carefully coordinated media coverage drew national sympathy for the protesters.

The change they achieved: Woolworth was integrated by that summer, and the nonviolent movement soon became SNCC (the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee) which went on to achieve further victories against racial injustice throughout the 1960s.

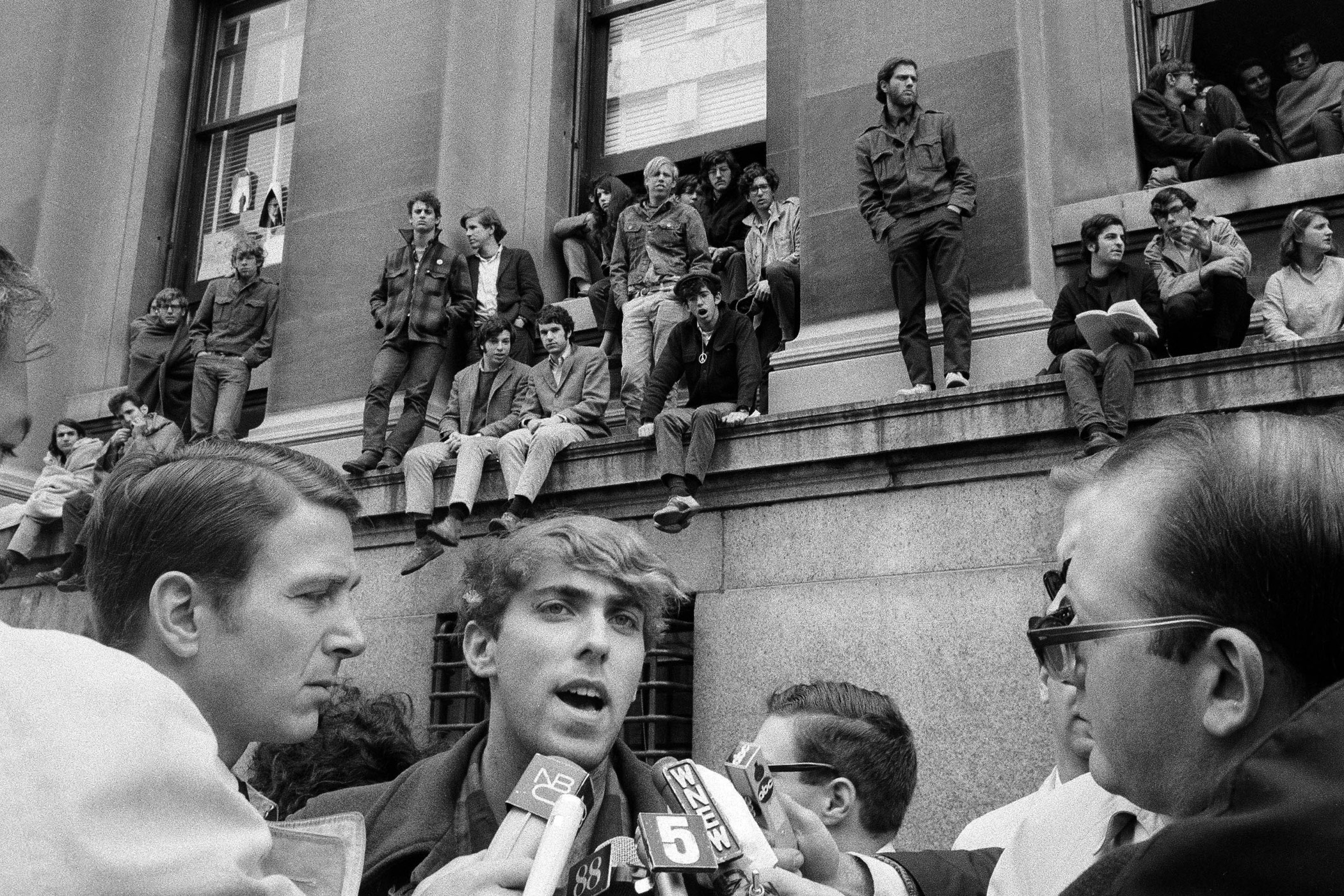

Harvard Protests ROTC on Campus, 1969

Tensions were high about the unpopular Vietnam War, and while Harvard students knew they had little chance of influencing the White House, they decided they could influence the school’s administration.

Their tangible goal: The students wanted Harvard to cancel the ROTC program (Reserve Officers’ Training Corps), which they thought made the university complicit in the war. They also wanted the university to stop evicting working-class people from real estate the administration wanted to develop, and they wanted the school to create a black studies program.

Their specific strategies: Students occupied University Hall, the main administration building on campus, and ultimately began publishing confidential documents they stole from the offices. When the administration forcibly removed them, the protesters won wider sympathy among other students and faculty.

The change they achieved: ROTC was downgraded to an extracurricular activity and stripped of special privileges, and African-American Studies is now one of the most robust departments at the school.

Columbia Divestment from Apartheid, 1985

Horrified by the stories of racial injustice coming out of South Africa during Apartheid, students at Columbia University wanted to make sure their university’s money wasn’t inadvertently funding state-sanctioned racism. In 1985, they demanded the university divest from South Africa (other schools, like Rutgers, had already divested).

Their tangible goal: To force the University to divest $39 million worth of stock it owned in American companies doing business in South Africa.

Their specific strategies: Students occupied administration buildings, chained themselves to the wall, and refused to leave until the university divested from South Africa. They stayed there for three weeks, until a judge ordered them to leave for safety reasons.

The change they achieved: Six months later, the administration announced it would sell off its holdings in companies that did business in South Africa, which amounted to 4% of the school’s total portfolio. While the administration did not attribute the decision directly to the sit-in, the movement was declared a success, and the sit-in model has been used to demand divestment from fossil fuels and from other industries students oppose.

See 7 Times Student Activists Created Change

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Charlotte Alter at charlotte.alter@time.com