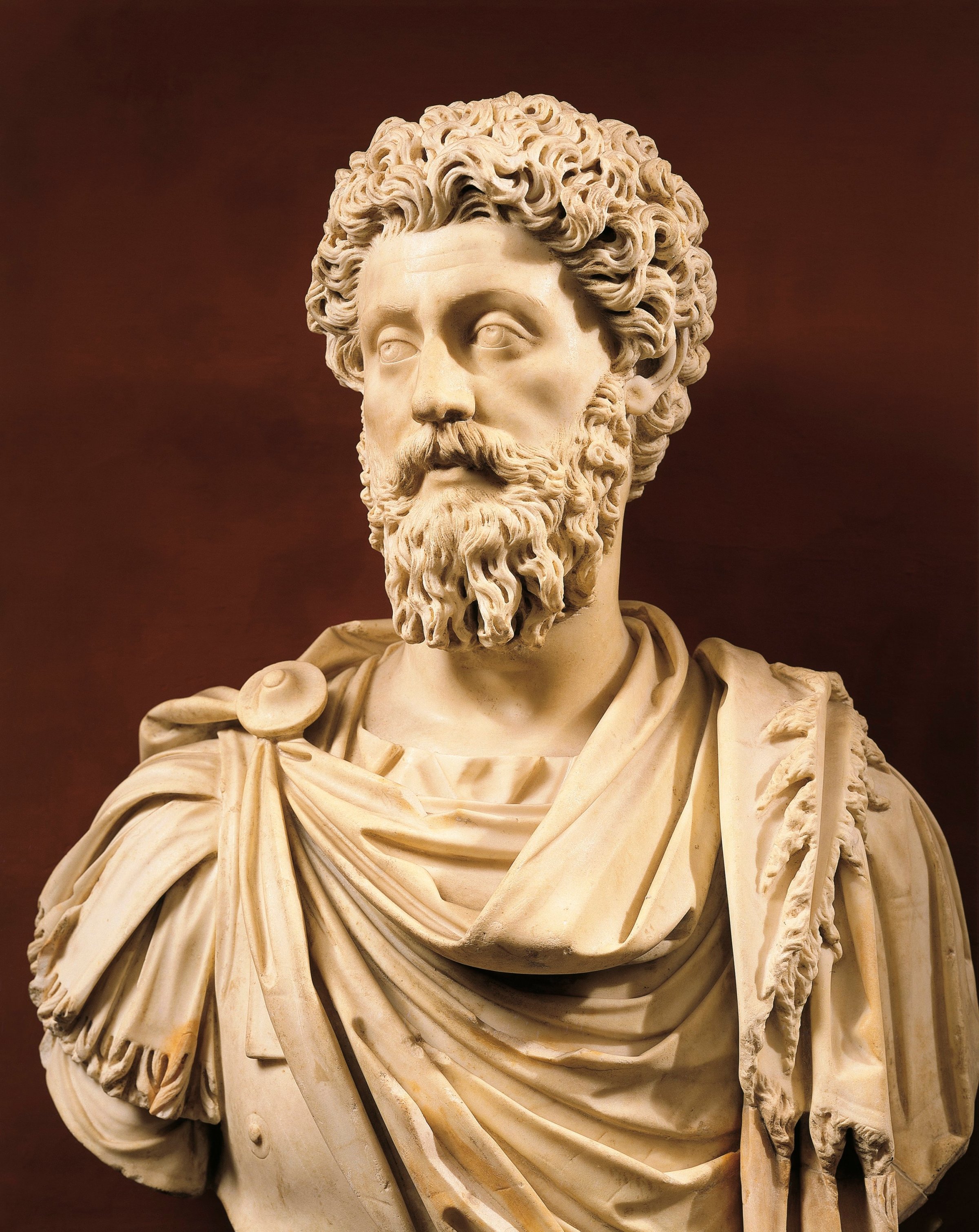

Marcus Aurelius has been read for 1800 or so years now and he’s arguably just as relevant today as he was when he was ruler of the Roman Empire.

Aurelius, the ruler of the Roman Empire for almost two decades, was also the author of the immortal Meditations. “Yet the title,” writes Gregory Hays in the introduction, “is one that Marcus himself would surely have rejected. He never thought of himself as a philosopher. He would have claimed to be, at best, a diligent student and a very imperfect practitioner of a philosophy developed by others.” Everyone who reads Meditations—from elementary school children to presidents—takes away some lessons. Be wary though, the book presents a dim view of human life.

To understand Meditations, we must first understand the role of philosophy in ancient life.

While there was certainly an academic side to philosophy back then it also had a more practical side expected to provide a design for living—”a set of rules to live one’s life by.” A need not met by ancient religion, “which privileged ritual over doctrine and provided little in the way of moral and ethical guidelines.” Philosophy was expected to fill the gap.

“The questions that Meditations tries to answer are metaphysical and ethical ones,” Hays writes. These are timeless questions that we are still asking. Why are we here? How can I cope with the stresses and pressures of daily life? How can I do what is right? How can I cope with loss and pain? How can I handle misfortune? How do we live when we know that one day we won’t?

Book one, a special section entitled Debts and Lessons, is “distinguished from the rest of the work by its autobiographical nature.” It consists of seventeen entries in which Marcus Aurelius reflects upon what he has learned from various influential individuals in his life.

Here are some lessons we can draw from book one.

Do Your Own Work

(From my first teacher): Not to support this side or that in chariot-racing, this fighter or that in the games. To put up with discomfort and not make demands. To do my own work, mind my own business, and have no time for slanderers.

Read Attentively

(From Rusticus) To read attentively-not to be satisfied with “just getting the gist of it.” And not fall for every smooth talker.

The Greatest Compliment

(From Sextus) … To show intuitive sympathy for friends, tolerance to amateurs and sloppy thinkers. His ability to get along with everyone: Sharing his company was the highest of compliments.

The Ruthlessness of Good Families

(From Fronto) … To recognize the malice, cunning, and hypocrisy that power produces, and the peculiar ruthlessness often shown by people from “good families.”

Staying on the Path

(From Maximus) … The sense he gave of staying on the path rather than being kept on it.

From his adopted father, Marcus Aurelius learned:

Compassion. Unwavering adherence to decisions, once he’d reached them. Indifference to superficial honors. Hard work. Persistence. Listening to anyone who could contribute to the public good. His dogged determination to treat people as they deserved. A sense of when to push and when to back off. … His searching questions at meetings. A kind of single-mindedness, almost, never content with first impressions, or breaking off the discussion prematurely. His consistency to friends-never getting fed up with them or playing favorites. Self-reliance, always. And cheerfulness. And his advanced planning (well in advance) and his discreet attention to even minor things. His restrictions on acclamations-and all attempts to flatter him. … His stewardship of the treasury. His willingness to take responsibility—and blame—for both. … And his attitude to men: no demagoguery, no currying favor, no pandering. Always sober, always steady, and never vulgar or a prey to fads.

[…]

The way he kept public actions within reasonable bounds-games, building projects, distributions of money and so on-because he looked to what needed doing and not the credit to be gained from doing it.

[…]

You could have said of him (as they say of Socrates) that he knew how to enjoy and abstain from things that most people find it hard to abstain from and all too easy to enjoy. Strength, perseverance, self-control in both areas: the mark of a soul in readiness-indomitable.

Still curious? Meditations is part of the Stoic Reading List.

Read next: A Philosopher’s Guide to Happiness

This piece originally appeared on Farnam Street.

Join over 60,000 readers and get a free weekly update via email here.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com