Allan Stewart Konigsberg was ostensibly born on December 1, 1935, in the Bronx. That’s the official version. Jerry Epstein relates that Woody told him that he was actually born on November 30, 1935. Epstein’s interpretation is that Woody always wanted to be number one. The family relocated to Flatbush, Brooklyn, and lived at several homes before settling at 1215 East Fifteenth Street when Woody was nine years old. Woody’s closest pals were Jerry Epstein, Jack Victor, and Elliott Mills.

“We had a very close, intense relationship from the time we met at twelve,” Epstein recalled. “He was psychic. He could see what people were all about. We were interested in magic, hypnosis, extrasensory perception, psychic phenomena. From the first day we immediately became very close friends … I lived on Avenue J; he on East Fifteenth Street between K and L. And then he moved to K and Fourteenth, the corner apartment building. I told him not too long after that he would be very famous, that he was the funniest person I ever knew … I was depressed as a teenager, and his humor lifted me.

“We would meet almost every day. He got involved in a crooked dice game. He went in with loaded dice he’d gotten from the Circle Magic Shop on Fifty-first Street and Broadway … Woody always took the position of having to get away with something. There’s the trickster element in him. Like he tricked me with a girl at a movie theater. All the girls I would bring around, he wanted. With him there was never a feeling of guilt; it was always you who was at fault, you were always wrong.”

Woody holed up in the basement at home, eating his dinner alone, reading his comic books (Superman, Batman, and Mickey Mouse), practicing his clarinet and his card and coin tricks. He stayed away from his mother’s critical remarks, the tension between his parents. “His parents were the oddest couple,” Jack Victor told me. “They had nothing whatsoever to say to each other. I never heard them exchange a single word.” His parents would actually not speak to each other for many months at a time. “It was like oil and water between mother and father,” Epstein said. “Marty had no religious feeling at all, while Woody’s mother came from an Orthodox background.” Allen was alienated from his parents. “I always ate alone—lunch, breakfast, all meals,” he told John Lahr. (I met with Woody himself for about an hour and a half at his office just as I was completing the book. Prior to that, I had sent him questions by email and he replied. He always made it clear that the book was not authorized by him, but he was unfailingly cordial.) “There were no books. There was no piano. I was never taken to a Broadway show or a museum in my entire childhood. Never.” It was a cultural barrenness and a total lack of emotional connection. His parents did not know what to make of him. His talent would remain invisible to them until the end, as is evident in the scene of Allen’s visit (with Soon- Yi) to his parents’ home in Wild Man Blues in their geriatric years. In effect they throw up their hands; their son could have been a pharmacist, he could have made a successful career. Look what happened to him.

Woody saw his first film, Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, when he was five, and, in a foreshadowing of a film he would create many years later, The Purple Rose of Cairo (in which a cast member walks out of the screen and participates in real life and later returns to the movie), the young Woody ran up to touch the screen. Like Cecilia in The Purple Rose, he figured out early that life was a hell of a lot better on the screen than in real life. He traveled to Manhattan for the first time at six. He was hooked by Manhattan and by the movies: Beau Geste, Pinocchio, Bambi, the Bob Hope and Bing Crosby Road pictures, Roddy McDowall in The White Cliffs of Dover, and Tyrone Power in The Black Swan. He saw the nonsensical surrealism of the Marx Brothers and Charlie Chaplin on-screen for the first time in 1944 at the Vogue Theater in Island.

By ten, Woody was high-strung like his red-haired mother, moody and prickly. He paid no attention at school and was frequently in trouble. His mother hit him constantly; she was the ultimate nag. Woody’s withdrawal from people and his coldness, his ability to keep his emotions in check, his tendency to use silence as a weapon of intimidation can probably be traced to his relationship with her. He saw at an early age from his mother’s example that uncontrolled emotion and anger were signs of weakness and helplessness. Yet his mother probably deserves some credit for his goal-oriented persistence, his tenacious work ethic, his enormous drive, his ability to work and never be distracted. She constantly reminded him, “Don’t waste time!”

His friends, Jerry, Jack, Mickey, and Elliott, got together with Woody and talked for hours about girls, about their innermost feelings, about what motivated people and how psyches worked. Woody was their leader. And uppermost on their minds were girls. “It was rough for Woody,” Epstein told me. “There was a girl he had a crush on, Nancy Kreisman. She didn’t know from him. She lived on Fourteenth Street between Avenue I and Avenue J. She had a dog named Woody. And that’s how he derived that name. That was spooky. He never made an advance on her. He was awkward and introverted with girls. He wasn’t comfortable. He was concerned about his looks. He was a nerdy type of person, growing up.” (Allen has said he picked the name for comical purposes.)

“He always had this concern about death, death looming” Epstein said. “And pessimism. The bottle is always half empty. Concerned with the underworld—death, ghosts, phantoms, cemeteries, graves. And hypochondriacal.”

The powerful counterforces to these fears and anxieties that Allen found for himself were writing, comedy, and music. Allen embraced them with overriding passion, and he does so to this day. It is only when he stops working that they return. But he always keeps working.

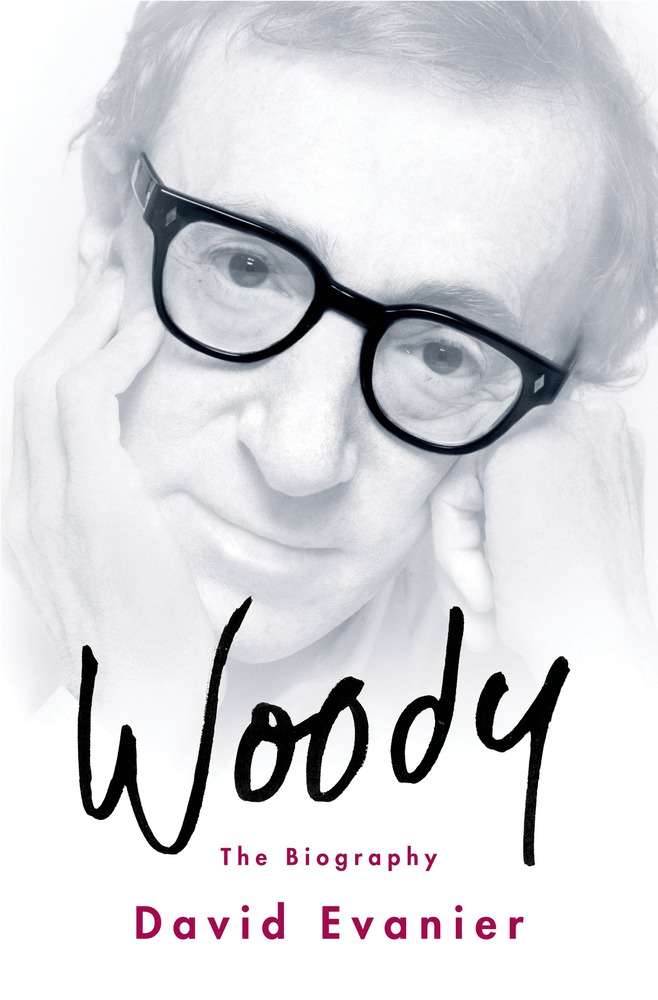

From Woody: The Biography by David Evanier. Copyright © 2015 by the author and reprinted by permission of St. Martin’s Press, LLC.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com