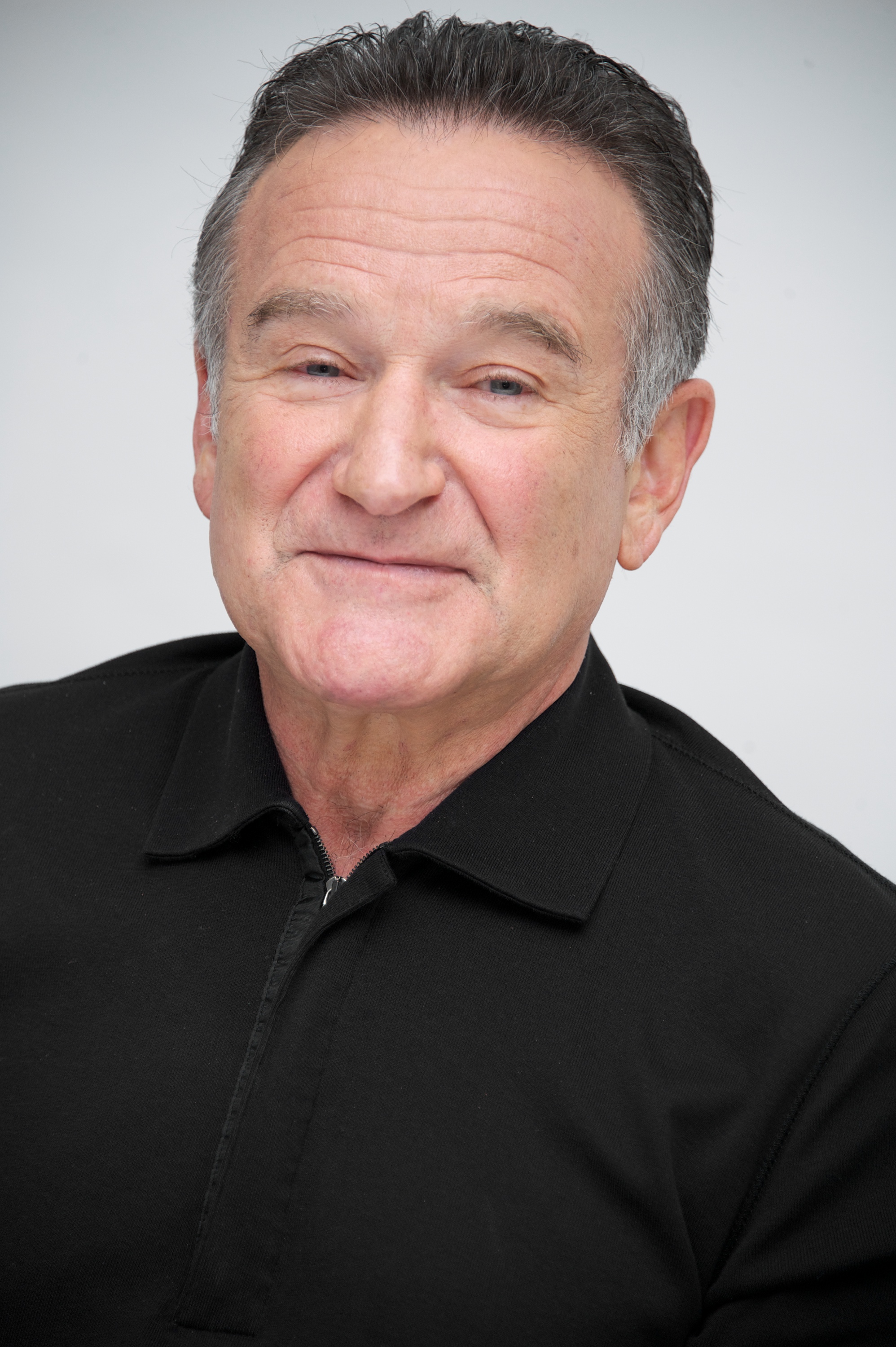

Robin Williams’ widow, Susan Williams, recently told People magazine that her late husband suffered from Lewy body dementia, a progressive brain disease with a constellation of symptoms. In the last year of his life, Williams experienced worsening anxiety attacks, delusions, trouble moving and muscle rigidity.

“I’ve spent this last year trying to find out what killed Robin,” Susan Williams told People. “One of the doctors said, ‘Robin was very aware that he was losing his mind and there was nothing he could do about it.'”

Here’s what you need to know about this complex, little-understood disease.

What is Lewy body dementia?

A progressive brain disorder in which microscopic protein deposits, called Lewy bodies, develop in the brain. Lewy body dementia (LBD) has symptoms that often include changes in thinking, problem solving, memory and movement. It’s the second most common type of dementia, after Alzheimer’s disease, and accounts for about 20% of all cases of dementia.

Still, says Angela Taylor, director of programs at the Lewy Body Dementia Association,“it’s decades behind Alzheimer’s disease or Parkinson’s disease as far as the scientific advances and understanding of the disease.”

How many people have it, and who’s most affected?

LBD affects about 1.3 million Americans, according to estimates from the Lewy Body Dementia Association, but the diagnosis rate is much lower. People who get LBD are often older adults ages 50 and up. Men are slightly more likely to get LBD than women, Taylor says, while Alzheimer’s disease is more prevalent in women.

What are the symptoms?

“There’s no single usual first symptom,” says Taylor, and people with the disease experience different combinations of symptoms and severity. Typical symptoms can include problems with abstract or analytical thinking and problem-solving. “In the beginning, their memories may be relatively intact, and they may not notice overt memory problems,” Taylor says. But people who have LBD often have problems with attention and alertness.

In addition to cognitive changes, other hallmark features are visual hallucinations and changes in movement that might resemble Parkinson’s disease, Taylor says. “Over time, people with LBD will lose freeness of movement; their muscle movements become more rigid, they may have a change in their gait,” she says. Facial expressions also reduce over the course of the disease.

Sleep is often altered as well, and people with LBD often have excessive daytime sleepiness. One major symptom is REM sleep behavior disorder, in which people physically act out their dreams, thrash, kick or hit, potentially injuring themselves and others. REM sleep behavior disorder can start even a decade before a person presents with cognitive symptoms, Taylor says. Along with hallucinations, REM sleep behavior disorder is one of the early indicators suggesting that a person has LBD and not Alzheimer’s disease, she says.

Why is it often misdiagnosed as Alzheimer’s disease?

LBD is often mistaken for Alzheimer’s disease, since the two share some similar symptoms like changes in thinking. Patients may even demonstrate brain pathology indicative of both disorders at the same time. But the two diseases are different. LBD patients often decline faster than Alzheimer’s patients; the average age of death is about six years younger in people with LBD than with Alzheimer’s. They also tend to have more functional impairment, and because of the complex symptoms, their care may be more challenging.

Getting the diagnosis right can be critical. People with LBD can become extremely sensitive to medication—especially some medicines that are used safely by someone who has Alzheimer’s disease, Taylor says.

How is it diagnosed?

A person must have a cluster of several LBD symptoms to get a diagnosis. After a medical history, clinical exam and neurologic exam, the doctor will likely order blood tests and brain imaging to rule out other causes for cognitive change, Taylor says. They may also refer a patient for a battery of cognitive tests.

“A lot of clinicians don’t screen for all the LBD symptoms,” Taylor says, which can make it challenging to differentiate between different types of dementia. “We always recommend people go to a memory disorder clinic which they can find often at a teaching hospital.”

Can it be cured or treated?

“Like Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease, the only treatments for LBD are to help manage the symptoms, to really provide improvements that help with quality of life,” Taylor says. “Unfortunately, there are no treatments that can alter the course of the disease, slow it down or stop it.” After symptoms start, a person generally has five to eight years to live.

This makes early detection important for both the patient and family. “The earlier we recognize the disease, the more we have the opportunity to help families have the knowledge and resources they need to help them understand what they’re dealing with,” Taylor says.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Caitlin Clark Is TIME's 2024 Athlete of the Year

- Where Trump 2.0 Will Differ From 1.0

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Mandy Oaklander at mandy.oaklander@time.com