In the summer of 1993, 16-year-old Shannon Taggart heard stories about a small town called Lily Dale, near her hometown in Western New York. Her cousin had visited to attend a “message service,” a public assembly in the woods where mediums give scattered communications to a curious crowd. When it came to his turn, the medium told him a strange family secret about the death of his grandfather—something nobody outside the family could have known.

“Since then I have been deeply curious about how someone could know such a thing,” Taggart, now a photographer, says.

Beyond its charming old Victorian vestige, this tiny hamlet located along Cassadaga Lake is the birthplace of a belief system that had dramatically influenced early scientific discovery and culture before fading into obscurity: Spiritualism.

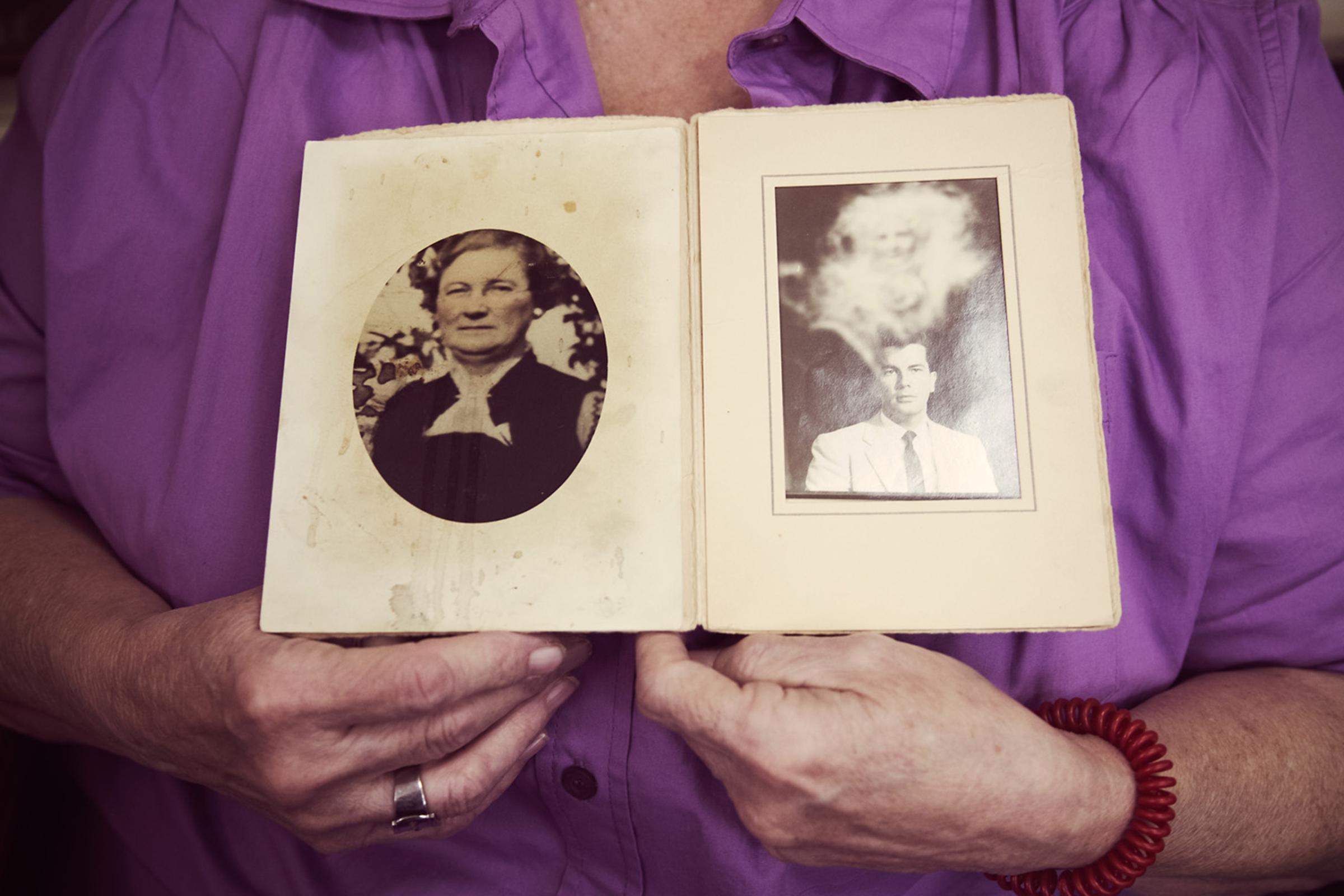

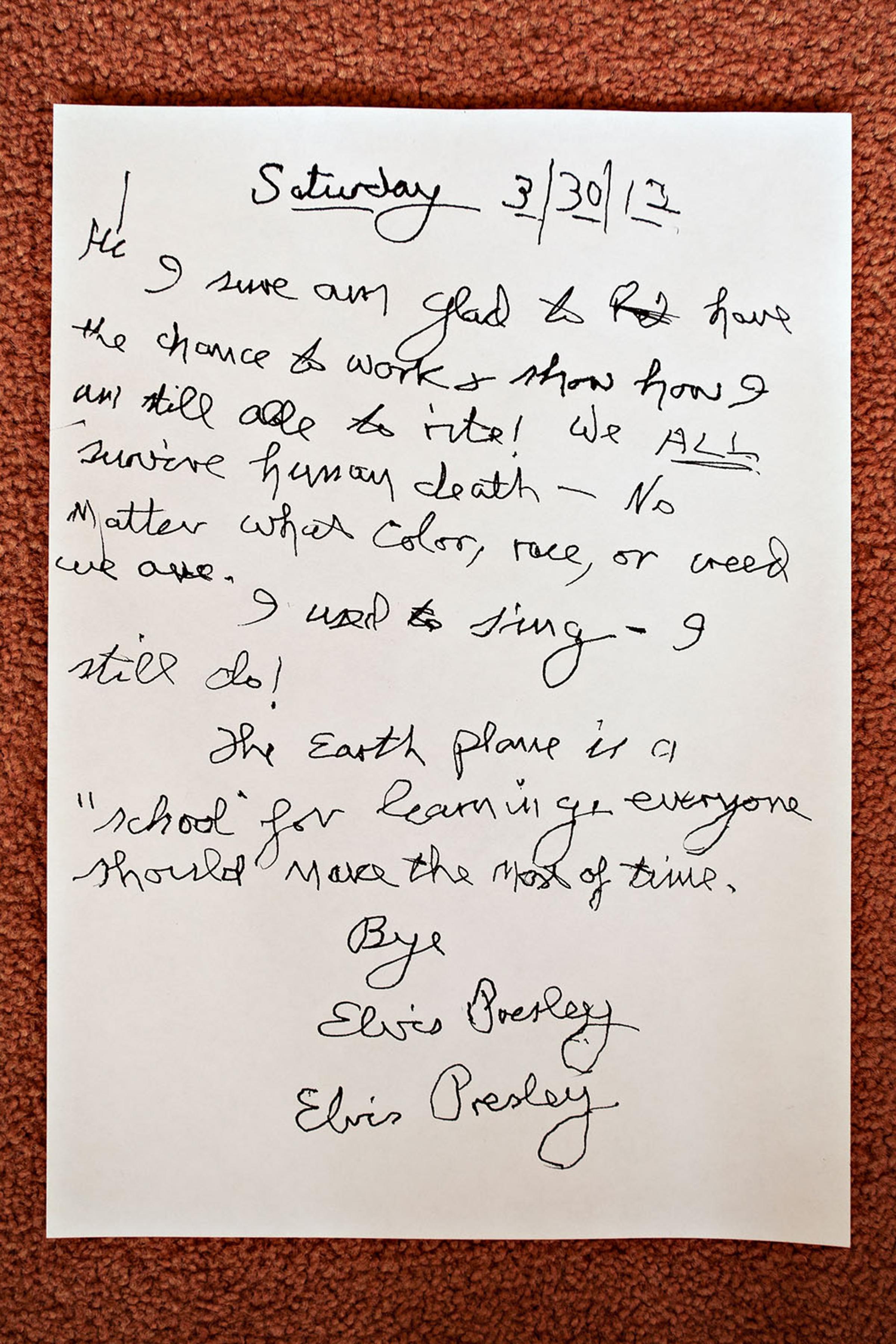

Spiritualism is a religion that is based on communicating with the dead through table tipping, séance rooms, ghostly rappings and spirit photography in dim-lit rooms, among other means. Its origins date back to the height of a religious movement that swept across Western New York. Emerging from it was Quaker leader Jamima Wilkonson, the Poughkeepsie Seer Andrew Jackson Davis, and two teenage girls known as the Fox sisters, who claimed to be in contact with the spirit of a murdered man buried beneath their home. The sisters, who said they could communicate with ghosts, were later revered as founders of Spiritualism.

The movement flourished across the world during the age of enlightenment in the 19th century, when science was changing people’s perception of certain invisible forces at work, such as radiation and electricity and the germ theory. A number of influential figures of the day were drawn to this practice. Historical records suggest that President Lincoln and the first lady Mary Todd held séances in the White House in an attempt to contact their dead son. For the last ten years of his life, Thomas Edison worked on a machine he hoped to use to talk to the dead. Spiritualists hosted suffragette leader Susan B. Anthony’s first speech at a time when it was illegal for women to speak in public, and author William Yeats found inspiration in the Spiritualist technique of automatic writing.

A Catholic raised New Yorker, Taggart has spent the last 15 years immersing herself in the philosophy of Spiritualism, returning every summer to the small town she visited as a young girl and later expanding her work to Spiritualism in the U.K. and parts of Europe.

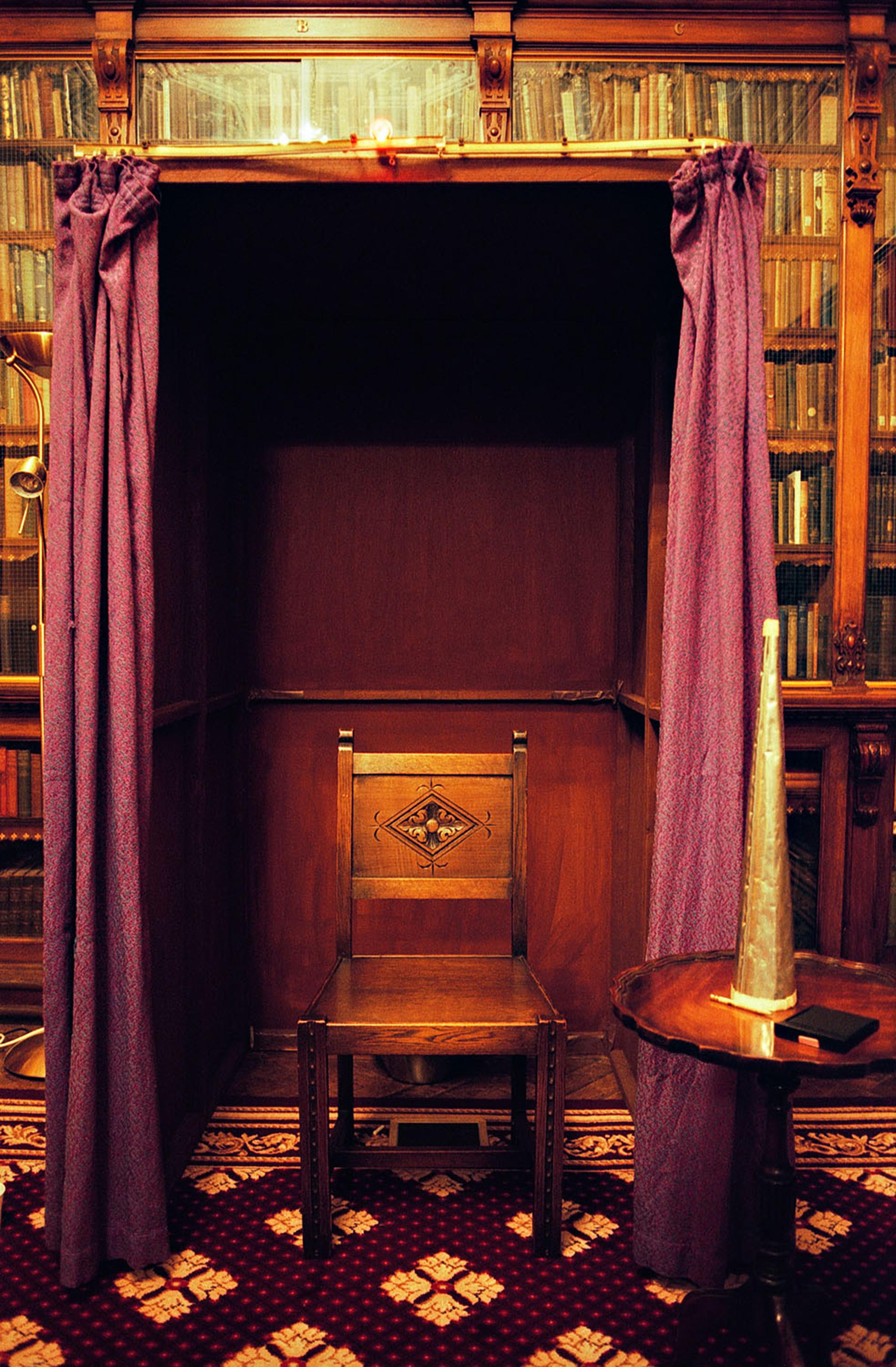

“I had readings, experienced healings, joined in séances, attended a psychic college and sat in a medium’s cabinet, all with my camera,” she says. “I peered into something truly mysterious. I stumbled upon a hidden world, an abandoned system with a storied history that became a resource and an inspiration for my own photographic theory and practice.”

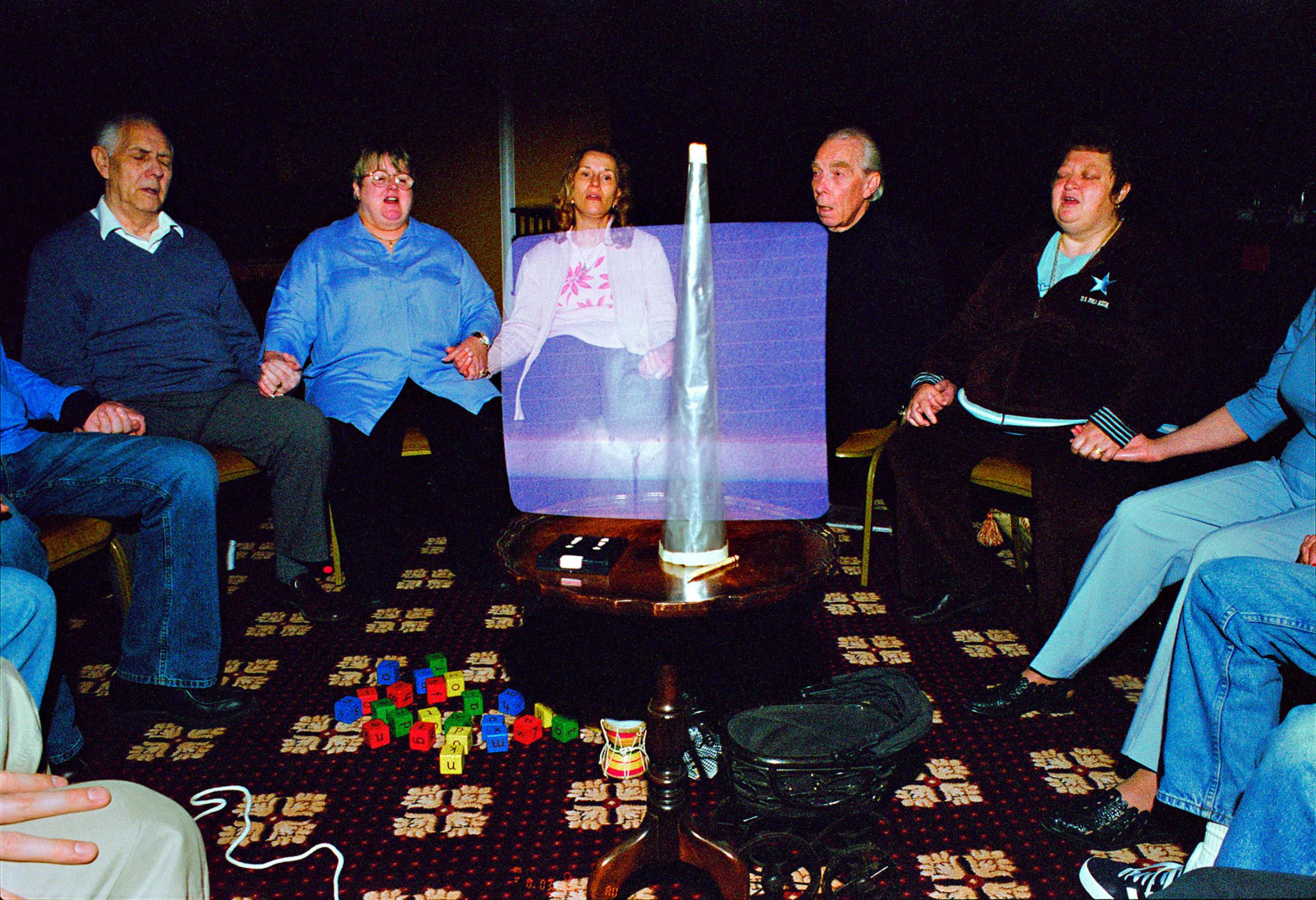

A combination of art, journalism and anthropology, Taggart’s images reflect a kind of serendipity with the camera. One photo depicts a woman throwing her head back while attempting to communicate with a spirit. An area of overexposure hovers in the corner. Another shows a woman who fades into a blur, administering healing to a young girl. And then there are shots of abstraction, motion and flare that hint at some unseen something. Or maybe it’s just a glitch of the camera. “I welcome the absurdity of those two responses,” she says.

For Taggart, the practices of Spiritualism are often misunderstood. “People often expect spiritualists or mediums to be perfect and give them exact proof of the afterlife,” she says “I think that’s impossible, but what spiritualists offer is a way to explore those aspects of our lives—thoughts of our loved ones, thoughts of death and thoughts of the afterlife. And they are so genuine in their practices.”

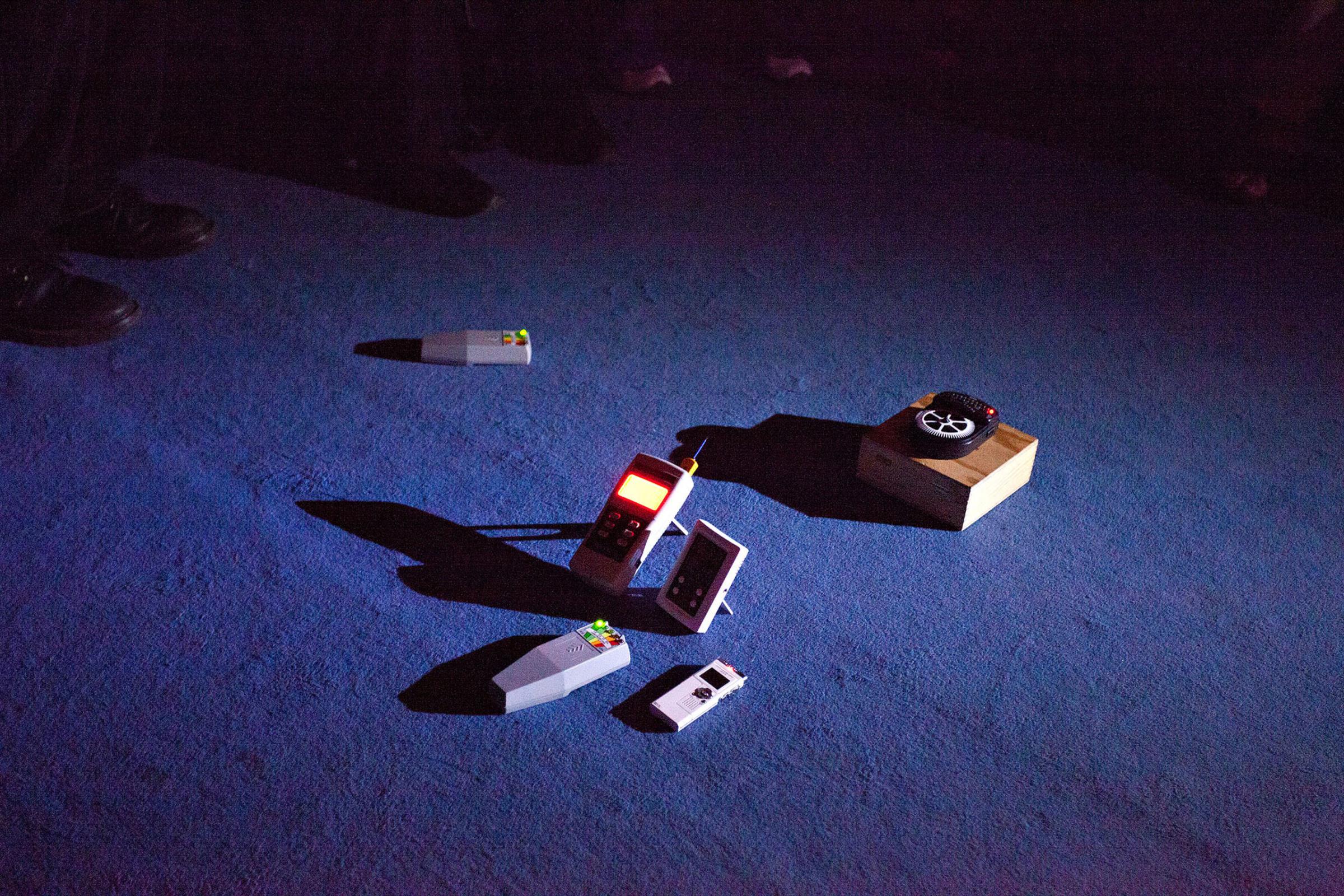

Taggart aims to go beyond the boundaries of what is considered wrong or unprofessional by pushing her camera to the edge of its functionality. She’s actually banking on accident and error. “Chance elements and the inherent imperfections of the photographic process offer an agent for the immaterial,” she says. “The resulting photographs are records from the exchange between a veiled presence and a visible body. And they invite questions about photography’s own conjuring powers.”

Since its beginnings, spiritualists have used technology as instruments for reception and transmission, using talking boards, tables, trumpets, slates, cabinets, radios, audio recorders and, perhaps most famously, cameras. “Spiritualism used photography to try to prove its theories and its practice, and photography used Spiritualism to explore the invisible,” she says. “Each system used the other to learn about itself.”

Shannon Taggart is a photographer, researcher and Programmer-in-Residence at the Morbid Anatomy Museum in Brooklyn, NY.

Paul Moakley, who edited this photo essay, is TIME’s Deputy Director of Photography and Visual Enterprise.

Rachel Lowry is a writer and contributor for TIME LightBox. Follow her on Twitter and Instagram @rachelllowry.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Biden Dropped Out

- Ukraine’s Plan to Survive Trump

- The Rise of a New Kind of Parenting Guru

- The Chaos and Commotion of the RNC in Photos

- Why We All Have a Stake in Twisters’ Success

- 8 Eating Habits That Actually Improve Your Sleep

- Welcome to the Noah Lyles Olympics

- Get Our Paris Olympics Newsletter in Your Inbox

Contact us at letters@time.com