A cold description of the latest archival release from Bob Dylan sounds like a satire on the worst possible box-set excesses. Titled The Cutting Edge 1965–1966, this 12th volume in the great bard’s bottomless “Bootleg Series” weaves into its sprawl false starts, in-jokes, studio blather, abandoned arrangements, half-baked song ideas–nearly everything that occurred in this protean phase of Dylan’s development but his sneezes.

The result could bankrupt the budget if not test even the most loyal fan’s patience. While you can get Cutting Edge in reasonably scaled two- or six-CD configurations (at $20 and $150, respectively), a third version could star in its own episode of Hoarders. It groans with 18 discs and includes extras as fetishistic as a strip of film from Don’t Look Back, the documentary of Dylan’s 1965 tour, and is available at a price just south of $600.

Luckily, all three sets feature a great number of full performances, and even the most extreme ephemera chronicle an unparalleled segment in the Dylan canon. The set bores into a feverish 14-month stretch–from January 1965 to March 1966–that produced three albums that stand among his greatest works and are also among the most influential in rock history. On Bringing It All Back Home, Highway 61 Revisited and Blonde on Blonde, Dylan ballooned from a folkie “protest singer” into an electric visionary beyond category. The songs–including the indelible “Subterranean Homesick Blues,” “It’s Alright, Ma (I’m Only Bleeding),” “Like a Rolling Stone” and “Sad-Eyed Lady of the Lowlands”–rocked with sounds and lyrics potent enough to launch a thousand bands and light countless imaginations.

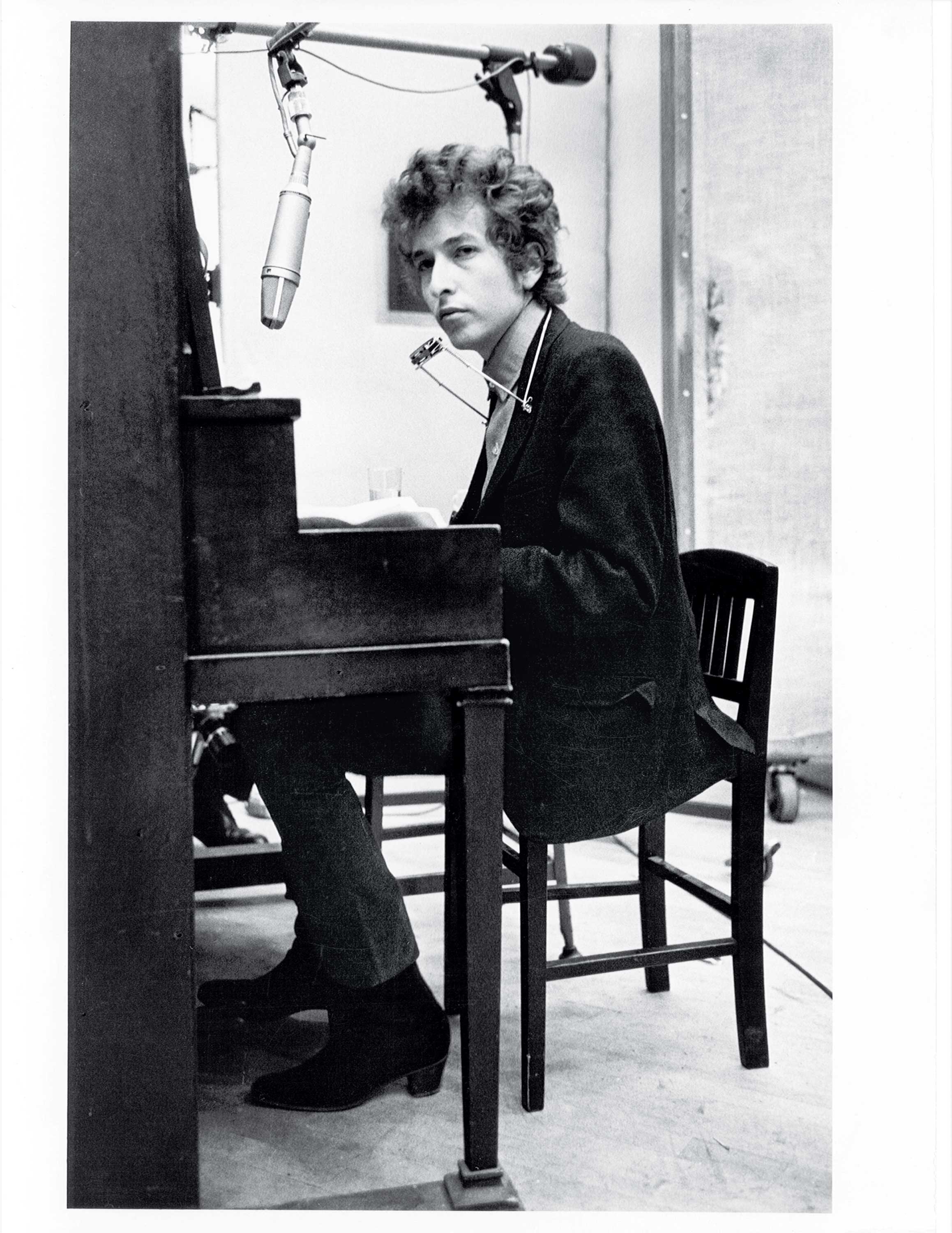

Cutting Edge gives us a sustained look at how Dylan pulled all that off. It’s a project about process, shadowing Dylan as he tests intriguingly different rhythms, arrangements, cadences and accompanists on songs as fixed in the public consciousness as “Positively 4th Street,” “Just Like a Woman” and “Desolation Row.”

Hearing Dylan knead his way into all the songs creates a riveting, you-are-there audio documentary. We listen in as a brilliant notion develops into a perfect work. Along the way, Dylan proves that a great composition can be turned in any direction. In four different versions of “It Takes a Lot to Laugh, It Takes a Train to Cry,” the song morphs from a casual shuffle (Take 1) to a sexy swagger (Take 3) to a full-bore rave-up (Take 8). We hear a less sarcastic run at “Stuck Inside of Mobile with the Memphis Blues Again,” a more ruminative “Desolation Row” with Dylan alone at the piano and an intimate treatment of “Love Minus Zero/No Limit.” In most takes, Dylan varies the melodies, revealing them as diamonds, able to refract the light from endless directions.

One of Dylan’s few mistakes was later solved by another artist. His attempt to use a drummer on “Mr. Tambourine Man” confounds him, yet one month after Dylan released his version the Byrds would release their cover, which nailed it, in the process perfecting folk-rock.

The two larger sets collect no fewer than 20 distinct runs at the game-changing single “Like a Rolling Stone.” They include a 21-second failed attempt to nail the start of the song, as well as isolated audio tracks of the master recording that present Mike Bloomfield’s escalating guitar figures on their own, plus Al Kooper’s oceanic organ surges with drums. No one in his right mind would need such trivia were it not for the gripping context of a period that saw Dylan realize a style he’d long been searching for–what he called “that thin … wild mercury sound”–which is compelling enough to make the six-CD version the one to buy. By contrast, the double-CD seems too cursory while the 18-wheeler could get you arrested for stalking.

Among a host of rarities, a few stand out. “Jet Pilot,” a gender-flipping roadhouse rocker backed by the Band, beat by five years Ray Davies’ own transvestite salute, “Lola.” There’s a grinding rewrite of the Beatles’ “I Wanna Be Your Man” (as “I Wanna Be Your Lover”), as well as an unnamed instrumental that serves as a virtual overture of motifs from Blonde on Blonde. Then there’s a track that will stop your heart: a solo piano version of “She’s Your Lover Now,” a song left off Blonde on Blonde. It’s the only recorded version of Dylan’s full, eight-minute composition, and it captures him at his most sneering and pained.

Other than that, no what-if moments arise. The better-known versions all remain superior in meter, polish and performance. But hearing Dylan prod the melodies and finesse the rhythms allows them to be reanalyzed with the Talmudic scrutiny they deserve.

Key in all this are Dylan’s vocals. Because of technical necessities of the day, he cut every one live, yet not a single take sees him dim the intensity of his engagement. Despite his keening tone and honking timbre, Dylan remains one of music’s most underrated singers. Together, these variations show that songs millions thought they knew still have secrets to reveal.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com