When Colombian musical legend Diomedes Díaz died in 2013 thousands attended his funeral. Colombia’s president called him a genius while his rags-to-riches life story was turned into a TV series. Now the Colombian Congress is considering a bill to honor the late singer.

But critics say the hero worship has gone too far. Here’s why. In 2001 Díaz was convicted of manslaughter for the strangulation death of his 24-year-old girlfriend.

“It’s true that Diomedes was a musical icon,” said Alirio Uribe, a Colombian congressman who opposes the bill. “But we can’t separate his artistic side from his personal troubles.”

Diaz’s art was composing and singing accordion-laced vallenato music which celebrates the joys of country living, all-night parties and falling in love. The genre, which is also heavy on bongo drums and the guacharaca, a ribbed wooden stick played with a fork, originated near the Caribbean coast of northern Colombia where Díaz grew up.

The son of farmers from an arid, cactus-lined village called La Junta, Díaz suffered from malnutrition as a child and lost his right eye when a playmate hit him in the face with a mango pit. But he had a knack for verse, developed a soaring voice and began singing with local bands. Over a nearly 40-year recording career, he sold millions of vallenato albums and CDs.

Today, his songs blast from bars and dance halls throughout Colombia and are staples at parties and weddings. His hometown has become a mecca for fans who come to see the people and places he sang about. Retired oil worker Héctor Suarez, who was visiting La Junta with his family, said: “Diomedes was our idol.”

But offstage Díaz was often out-of-control. He was a heavy drinker and cocaine user who sometimes took the stage inebriated or missed gigs altogether. He was also a notorious womanizer, according to relatives, fathering at least 28 children.

“For Diomedes it was all sex, drugs and vallenato,” said Mauricio Figueroa, an actor who plays the role of Díaz’s record company manager in the top-rated Colombian telenovela The Chieftain of La Junta.

In 1997 Díaz got into a drunken argument with Doris Adriana Niño, who had just learned that another of the singer’s girlfriends was pregnant with his child. Prosecutors argued at his trial that Diaz held his hands over Niño’s nose and mouth to stop her from screaming but ended up strangling her. Then, his bodyguards dumped her corpse in a cow pasture.

Díaz claimed to know nothing about the crime but was found guilty of manslaughter and sentenced to 12 years in prison. But instead of jail Díaz hid out with paramilitary drug traffickers who were some of his biggest fans. When police tried to arrest the singer, the militias drove them away.

Díaz finally turned himself and was sent to a prison near his hometown where he received VIP treatment. He was even allowed to set up a recording studio in the warden’s office and lay down the vocal tracks for several CDs. Díaz accumulated points for good behavior and ended up spending just 26 months behind bars. He then launched a triumphant comeback tour of soccer stadiums.

After Díaz died of a heart attack two years ago at age 56, President Juan Manuel Santos declared: “He brought vallenato to its highest point of creativity.”

So why is it that Colombians are so willing to overlook Diaz’s dark past? Some say that in a macho society like Colombia’s, violence against women is common – even accepted – in many parts of the country. Says Yalile Giordanelli, the producer of The Chieftain of La Junta: “The problem isn’t just Diomedes. His actions reflect a country and a culture.”

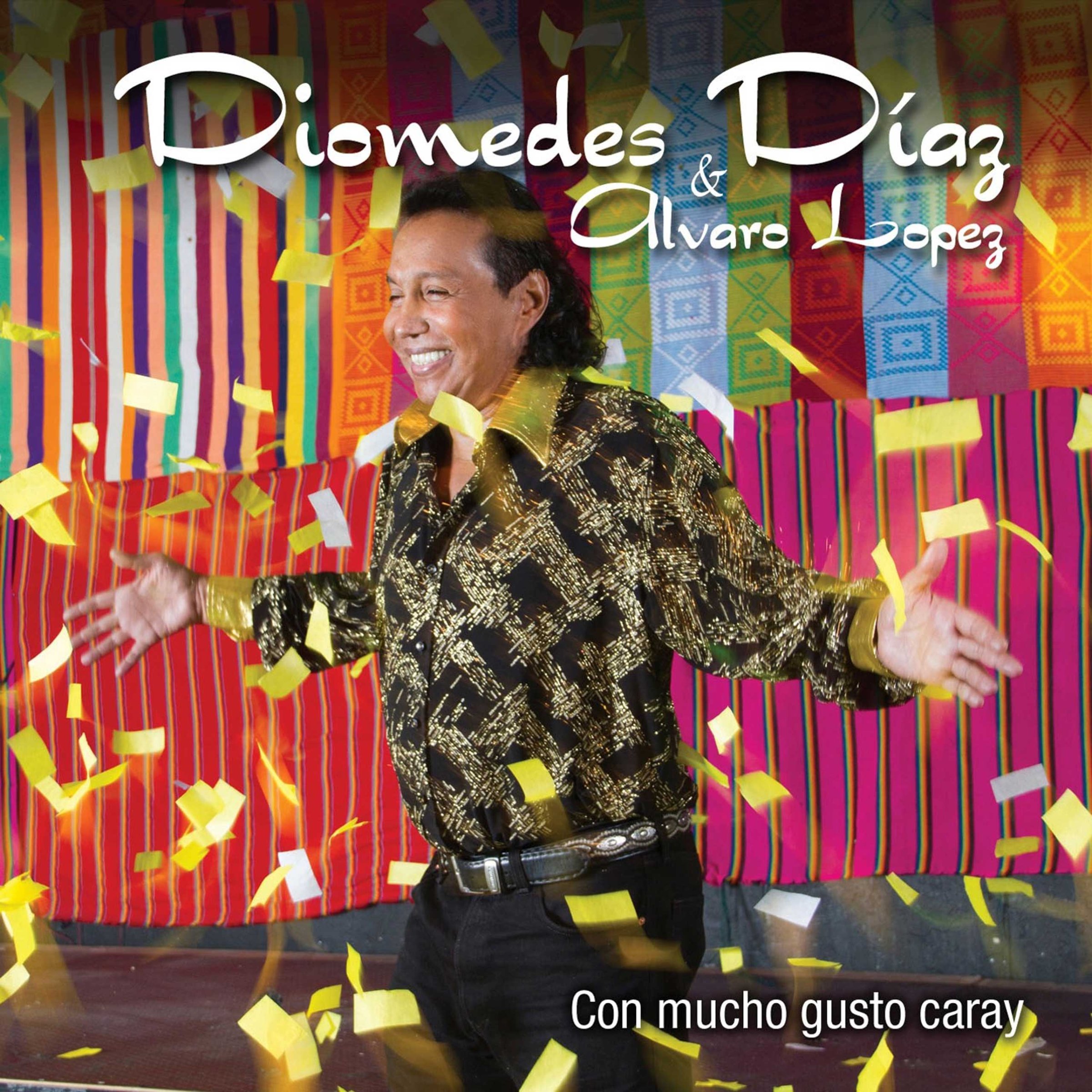

As a result the killing of Niño is widely viewed as a minor blemish on Díaz’s otherwise stellar career. Or, in the words of Álvaro López, who played accordion in Díaz’s band: “No one is perfect. Diomedes had good points and bad points but he made vallenato music great.”

The Colombian Congress seems to agree. It is now considering a bill to honor Díaz for his lifetime contributions to Colombian folklore. But some say the bill makes no sense given that these same legislators recently passed a law that imposes tougher punishments on those who kill women or girls.

“This is an embarrassment,” said Angélica Lozano, a lawmaker who vehemently opposes the bill.

Supporters have drummed up all sorts of justifications. One lawmaker noted that many Colombian streets and statues honor Spanish conquistadors “who wiped out entire populations.” According to this logic, Colombia already pays tribute to killers — so why not Díaz?

Uribe predicts the bill will eventually pass because so many lawmakers are Díaz fans. Meanwhile, pilgrims to the singer’s hometown insist that the vallenato king is more saint than sinner.

“Díaz loved women and wrote many songs about them,” said Jose Leon Salinas, an accountant from a nearby town. “He had no reason to get his hands dirty.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Trump’s Message Worked on Latino Men

- What Trump’s Win Could Mean for Housing

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Sleep Doctors Share the 1 Tip That’s Changed Their Lives

- Column: Let’s Bring Back Romance

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com