This post is in partnership with the History News Network, the website that puts the news into historical perspective. The article below was originally published at HNN.

Each fall I teach an undergraduate course titled “Native Americans in the South.” The class is designed for juniors and combines historical narrative with analysis of specific events and/or Native American people in the Southeast. On the first day of class I begin by asking students why they’re taking the course and inquire if any have Native American ancestors. This year proved typical: five of forty students claimed they are descended from a great-great Cherokee grandmother.

I’ve become so use to these declarations that I’ve long ceased questioning students about the specifics of their claims. Their imagined genealogies may simply be a product of family lore, or, as is occasionally the case, a genuine connection to a Cherokee family and community.

All of these students – whether their claims are flights of fancy or grounded in written and oral evidence – are part of a growing number of Americans who insist they are descended from one or more Cherokee ancestor(s).

According to the United States Census Bureau, the number of Americans who self-identify as Cherokee or mixed-race Cherokee has grown substantially over the past two decades. In 2000, the federal Census reported that 729,533 Americans self-identified as Cherokee. By 2010, that number increased, with the Census Bureau reporting that 819,105 Americans claiming at least one Cherokee ancestor.

The Census Bureau’s decision to allow Americans to self-identify as belonging to one or more racial/ethnic group(s) has meant that “Cherokee” has become by far the most popular self-ascribed Native American identity. “Navajo” is a distant second.

Census data is but the tip of the iceberg. Search the Internet and one will quickly be left with the impression that the Cherokee family tree not only stretches out over North America, but to places as distant as Central America, Scotland, the central Pacific, and even Australia.

In the United States alone, the Cherokee Nation of Oklahoma estimates there are over 200 fraudulent groups claiming to be Cherokee. Visit websites devoted to genealogy, and one will find scores of Americans expressing their disappointment when DNA testing contradicts family legends about great, great grandma being Cherokee.

So what’s behind all of this?

There are three major reasons for the ubiquity of claims about Cherokee ancestry. The first reason can be found in the success of Cherokee governance. Since 1970, when President Richard Nixon ended the period known as “termination,” three federally recognized Cherokee tribal governments have successfully administered to the local needs of Cherokees. These governments are the Cherokee Nation of Oklahoma, the United Keetoowah Band of Cherokee Indians in Oklahoma, and the Eastern Band of Cherokees.

Cherokee authorities have therefore played a leading role in keeping Cherokee history and culture alive through the use of the arts, education, and historical preservation. Language immersion, for instance, has ensured that the Cherokee language is still read and spoken in Cherokee communities. Indeed, the Cherokee language has transcended the boundaries of Cherokee communities with the Cherokee Nation of Oklahoma teaming up with tech giants Apple, Microsoft, and Google to get Cherokee language and translation apps on iPhones and smart phones throughout the United States.

A second reason for the popularity of Cherokee identity is the place that Cherokee history and culture has in American popular culture. From the 1959 pop song “Indian Reservation (The Lament of the Cherokee Reservation Indian),” which the rock band Paul Revere and the Raiders popularized in 1971, to the National Park Service educating generations of Americans about Cherokee removal, the Cherokee people have occupied an important place in the popular narrative of the American history.

While American school children often finish their formal education with only a cursory understanding of Native American history, it’s important to acknowledge that many walk away with at least a cursory sense of the injustice inflicted on Cherokee people at the end of the late 1830s. The story of the Trail of Tears engenders a degree of compassion for the historical experiences of Cherokee people, even if some people use that compassion for self-serving purposes to articulate an individual identification with the Cherokees.

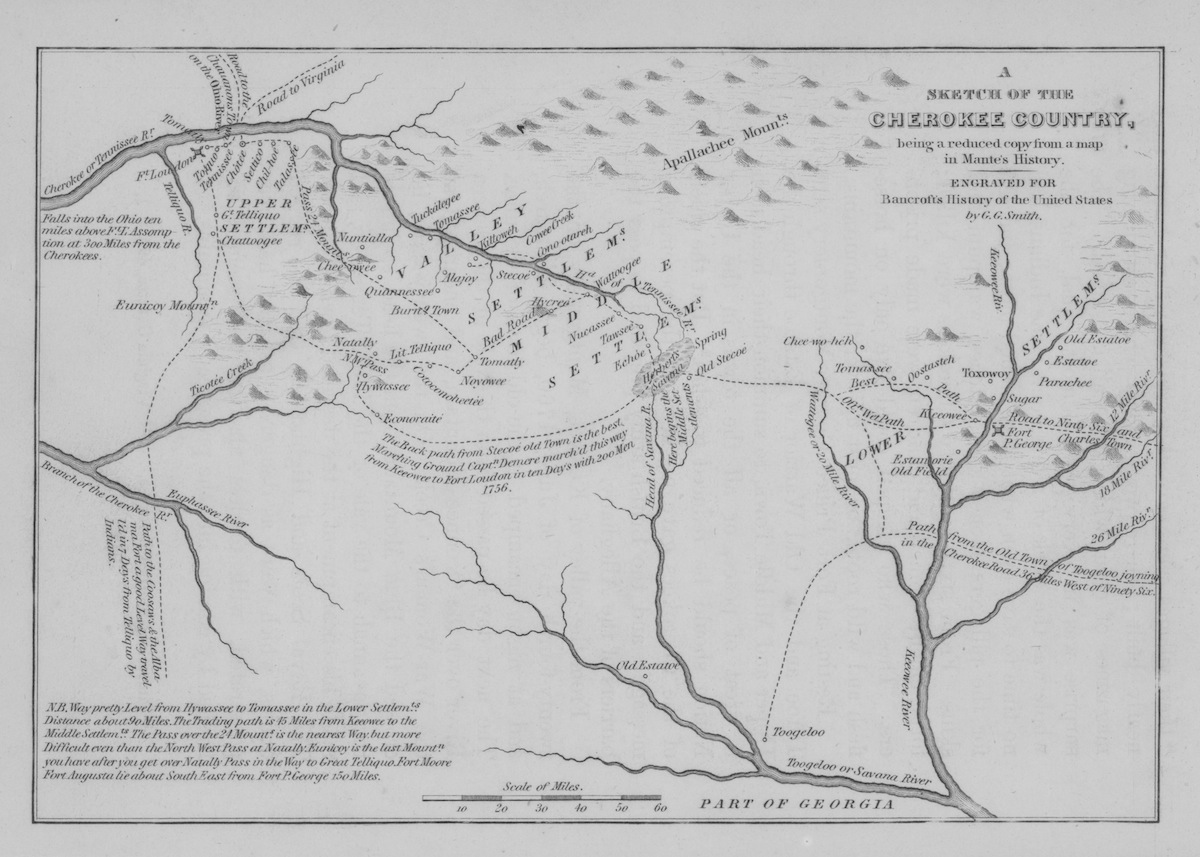

A third, and more significant reason, is the actual history of the Cherokee people. As European colonialism engulfed Cherokee Country in the Southeast during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, Cherokees began innovating their social and cultural traditions to better meet the challenges of their times. Cherokee chiefs engaged in diplomacy and trade, some Cherokees relocated their towns to escape aggressive frontier settlers, while still others intermarried with people of European (and occasionally, African) descent. The result, by the time the United States became a republic, was a culturally dynamic, ethnically diverse Cherokee population.

Increasingly, the Cherokee people also became a geographically dispersed population. The encroaching Anglo-American settler frontier, greedy slave owners who coveted Cherokee lands, and federal officials who extracted land cessions from Cherokee chiefs through treaty-making slowly but surely dispossessed the Cherokees of their Southeastern homelands. There can be no doubt that the forced removal of the Cherokees to Indian Territory (modern-day eastern Oklahoma) during Andrew Jackson’s presidency was one of the most inglorious episodes in American history, but the process of scattering the Cherokees all over the earth started long before the Trail of Tears.

It’s the development of diasporic Cherokee communities that may help to explain why the Cherokees occupy a prominent place in our collective historical consciousness. Scattered over the earth by the often-cruel forces of settler colonialism, the Cherokees endured and flourished. The Cherokee people’s history is a compelling story; perhaps that’s why so many Americans hope to find a Cherokee in their family tree.

Gregory D. Smithers is an Associate Professor of History at Virginia Commonwealth University and the author of The Cherokee Diaspora: An Indigenous History of Migration, Resettlement, and Identity (Yale University Press, 2015).

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com