On Wednesday night, the U.S. House passed a bipartisan budget agreement, which, if passed by the Senate, will end the extended partisan struggle that began with the 2010 elections, forestalling another showdown until after the 2016 elections. The recent political paralysis is reminiscent of a struggle that also began with an election.

In 1994, Republicans with a radically conservative view of the role of government, led by Newt Gingrich, won a stunning victory that gave them control of both houses of Congress. In 2010, equally conservative Republicans captured the House and, in 2014, added the Senate. In both the earlier periods and today, the ascendant Republicans have sought to use the budget process and the threat of government shutdown—even government default—to force a Democratic President to accept their agenda.

The so-called Paul Ryan budget—a definitive statement of Republican policy objectives—is essentially the Gingrich 1995 agenda reborn. It proposes to privatize and cut Medicare, block grant and cut Medicaid, block grant and cut the anti-hunger programs, make deep cuts in discretionary programs, and increase tax cuts for the wealthy. In 2011, Republicans were willing to use the threat of a default even at the risk of a world-wide financial meltdown to extort deep, long-term cuts in domestic discretionary spending, although they failed to achieve the radical changes in entitlements they sought.

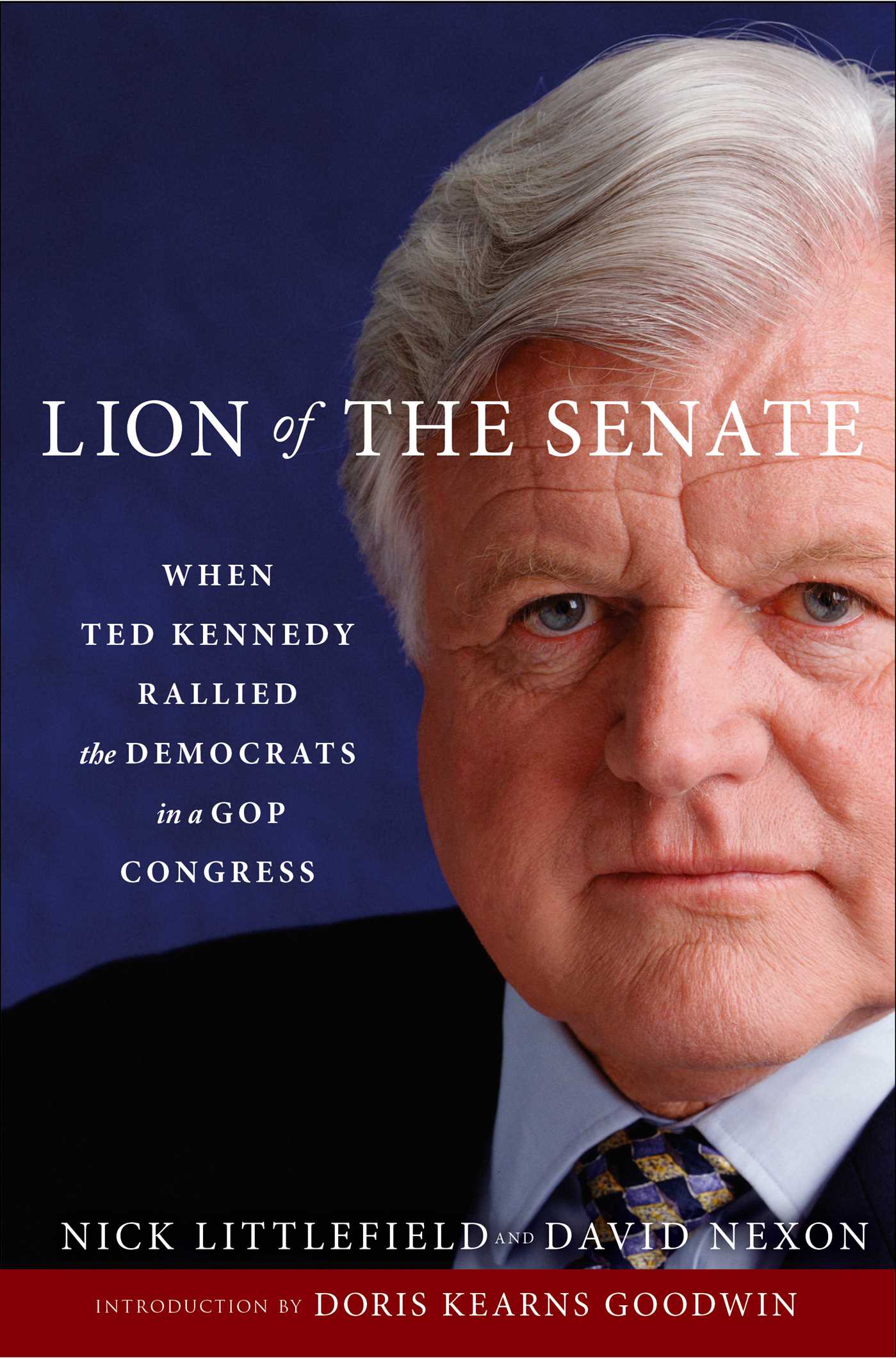

In 1995, Senator Edward Kennedy rallied his party to stand up for historic Democratic values. He brought a special mixture of political gifts to this fight—and President Bill Clinton used the bully pulpit and the veto pen to great effect. But another important key to success was educating the public. When the voters truly understood the Republican agenda, the political price of sticking with their program was so high that they ultimately backed down.

But educating the public required a sustained effort. In 1995, scarcely a week went by when Congressional Democrats did not stage a rally, conduct a forum, release a study, or organize a floor debate to draw attention to what the Republicans were doing. When the government shutdown finally came, the building blocks of public understanding of what was at stake were already in place.

By contrast, the Democratic effort since 2010 has been less effective. In The Center Holds, Jonathan Alter reports that when focus groups were asked about the Ryan budget provisions, the participants’ primary reaction was disbelief. They simply could not fathom the idea that any politician would propose such a program.

In the new budget deal, Republicans suspended efforts to force through major entitlement change and allowed a temporary, partial add-back of some domestic discretionary spending. But the remaining deep, long-term cuts in discretionary spending would, among other misguided policies, restrict the path to college for low income students, reduce access to Head Start for disadvantaged children, slow scientific research, and continue to ignore crumbling infrastructure. Essential public needs will continue to be starved, and a renewed effort to push through radical changes in social entitlement and safety net programs has only been deferred.

It’s likely that the public understands none of this, and Democrats need to make them a focus of the presidential election; if a Republican president is elected in 2016, enactment of the Ryan budget will likely be the first order of business for the new Congress.

The pressing national problems we face require new solutions. As Senator Kennedy understood, very little becomes law without bipartisan support. Even during the polarized environment of the Gingrich Congresses, Kennedy was able, against all odds, to secure passage of a minimum wage increase, a ground-breaking health insurance reform bill, and the largest health entitlement expansion since Medicare and Medicaid—the Child Health Insurance Program.

Kennedy was a master of energizing the public and the party. But two additional keys to his success are often lacking today. First, there were the strong personal relations that he built with colleagues on both sides of the aisle. His partnership with Orrin Hatch is well known, but he was also able to strike up alliances on a wide range of issues with Republican senators as diverse as Strom Thurmond, Pete Domenici, and Trent Lott, among many others.

When Kennedy partnered with a Republican, it was because they had a common interest in an issue, not because Kennedy charmed them. But the personal relationships and trust he built made the alliances possible and the necessary compromises more palatable. And that was the second key to Kennedy’s success: He recognized that compromise was necessary—not on the ultimate objective but on the means to achieve it. He was willing to settle for a half a loaf—or even a slice if that was the best he could get—but he always aimed high and never compromised his principles.

As people of good will on both sides of the aisle struggle to navigate today’s troubled political waters, Kennedy’s leadership has much to teach them.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com