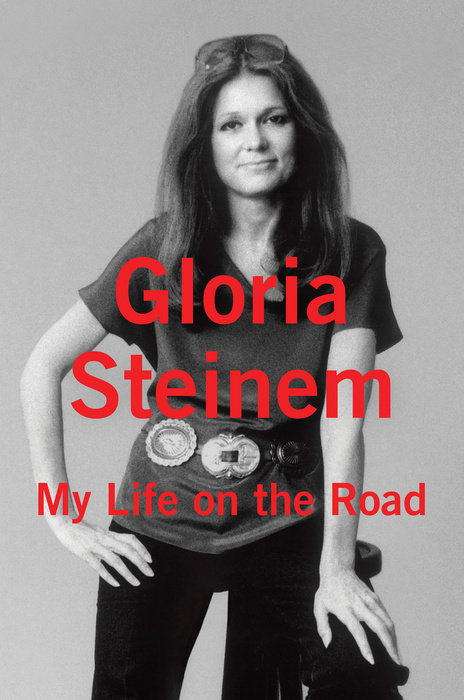

It’s been a busy half-century for Gloria Steinem. The feminist, activist and founder of Ms. Magazine has been crisscrossing the globe since the 1960s, spreading her message of equality. All that crisscrossing has become a muse itself, for her new travel memoir My Life on the Road, out this week, which traces Steinem’s footprints and voyages from her vagabond childhood through her career. TIME spoke with Steinem about the book, the election and feminism lately.

TIME: Why do you think travel is especially important for women?

Steinem: If you think about all of the great voyage classic tales, all the way to Jack Kerouac, it’s been male territory. I can understand why it has been viewed as dangerous for women, and also women have often been literally prevented from leaving home, as they still are in some parts of the world. But statistically speaking, the road is actually safer than staying at home, ironically, because, for instance, in this country, the place a woman is most likely to be beaten or murdered is in her own home. I don’t mean to be depressing about this, but statistically the road is somewhat safer. And it’s everyone’s right to be on the road and to travel, so women should be able to make that choice.

What do you read on the road?

Mostly I read my notes about where I’m going and who I’m going to meet. Sometimes I’m able to have a book with me, but mostly it’s so intense that I can’t even take notes, much less read.

Your book is dedicated to a doctor who referred you for an abortion when you were 22, but who made you promise never to say he’d helped you. Why did you dedicate it to him?

You know, in a way I don’t know why I didn’t before, but I had been dedicating my books to my family, to my friends, to people who had helped me with that particular book, and of course I thank other people for this book, too. But it just seemed time. It’s clear that he could no longer be alive, I’ve kept my promise not to disclose his name while he was alive. But also the whole atmosphere and understanding of reproductive freedom as a fundamental human right is with us now as a majority view. Of course there’s a lot of opposition to it but it is a majority view. I thought it was time that he, who was a pioneer, should be thanked.

What do you think is the single biggest threat to reproductive rights today?

Patriarchy 101. I mean, the very definition of patriarchy is that men control women’s bodies in order to control reproduction. So the idea that that is moral or okay is the greatest adversary. In fact, it’s a simple human right for each of us to control our own physical selves. But for women, because that means controlling reproduction somewhat more than it does for men, it’s been controversial and undermined and criminalized and made dangerous and it’s simply a human right. I think we’re moving toward a principle you might call bodily integrity, that is, the power of the government stops at our skins—for men and women. We may be imprisoned but we can’t be invaded against our will.

What troubles you most about the current attacks on Planned Parenthood?

They are attacks on a fundamental human right, which is, in women’s case and men’s, too, reproductive freedom, the right to decide whether and when to have a child. It’s important for men, too—men have sometimes been faced with involuntary sterilization and all kinds of criminal invasions, but obviously it affects women much more. So the very idea that the government or a religion has the right to make that decision for you is the problem. The anti-reproductive freedom groups in this country seem to have tried various tactics—first it was demonstrating against, burning, and bombing abortion clinics and murdering doctors, and [they] seemed surprised that this wasn’t popular, that this wasn’t viewed as pro-life. And pretty continuously they’ve been striving to get a so-called “human life” amendment to the Constitution that has proved to be impossible, so now they are focusing on state legislatures where those bodies are often in very unrepresentative right-wing control anyway for a whole lot of economic reasons. So they can in those state legislatures impose so many impossible restrictions on the physical layout of clinics themselves that they have been able to shut down clinics in many states.

What do you think of the trend of brands and celebrities participating in a commodification of feminism?

It depends; it’s not for me to judge whether it is commercial or sincere. It was commercial when Virginia Slims had “You’ve come a long way, baby,” but when it’s an individual person, the sincerity of it and the reality of it is really not for me to judge.

What about brands like Dove and athletic wear lines?

Well, Dove advanced the cause in their imagery by using women who were not conventionally slender—they photographed women who were many different sizes and shapes and colors, and I thought that was an advance. Obviously we’re not going to be liberated by buying a bar of soap, but it is helpful to see people who look like you in ads, as opposed to people who only look like models.

Who is a pop culture figure who incorporates feminism into their brand who you think is advancing the cause well?

It’s hard to say because most of the people I think of are self-created—they’re bloggers, there’s Lena Dunham, they’re more obviously talking about feminism in a very clear way. But I did think, for instance, when Beyoncé put “feminist” in huge glowing letters across the stage, because she was giving the definition [by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie]—actually [Chimamanda] had been on the cover of Ms. Magazine and then Beyoncé was on the cover, and I think they perhaps knew each other that way—it’s good, especially when we have Rush Limbaugh talking about “Feminazi” every day.

Women in Hollywood are in such a struggle now to get equality with male filmmakers. What was a woman-directed or -written movie that you’ve loved?

Trainwreck, to think of the one I most recently saw. First of all, it was the summertime, it was the weekend, it was in my neighborhood, which means most people go away, and [the theater] was absolutely full. I think it was the first time I’ve ever watched a very sexual, over-the-line movie and not felt endangered. I knew I was not going to be humiliated, eviscerated, because it was Amy Schumer’s movie. I don’t think I had ever been sure of that before in a very sexual movie.

What do you think of Playboy getting rid of the nude photos?

I was out of town when that happened, and someone emailed me that question, but I said it’s as if the NRA said we’re no longer selling handguns because now assault weapons are so available. For Playboy to change, they would have to change their braincells, their language, their title, and every thought they’ve ever had. It’s obviously not a change. I guess they’re not doing so well, you would know better than I, but I was just talking to somebody who had been offered the editorship because it was doing poorly, so I gather they’re looking to catch up in some way.

Is there anything good about Playboy compared to online pornography now?

It’s not as violent and sadistic as some other magazines and online pornography, but it’s a question of degree, not kind. They seem to have had a rule called “women can’t win,” even in fiction. The title alone is absurd, “playboy.” I was thinking about this the other day: suppose Hugh Hefner had never existed, and I as a feminist wrote a novel making up such a man, they would call me anti-male! They would say, “This can’t possibly be, a guy as ridiculous as this.”

There are still some older Democratic women who don’t support Hillary Clinton. Why do you think she’s polarizing among women who share her ideology?

In the book I talk about my trying to answer this question when she was running for the U.S. Senate, and I wouldn’t try to attribute motives to people I don’t know, but I had the impression then that she was threatening to some women because she was an implicit criticism of their lives. She had done more, despite being a woman. She had a partnership with her husband who respected her intellect and political ability, and they did not. And also I think in a larger sense, we are all, women and men, mostly raised by women, so we may associate female authority with childhood. It may seem threatening, we may even feel regressed to childhood when we see a powerful woman. That happens more to men, I think that’s part of the reason that some otherwise very professional male journalists have said some pretty dumb things in 2008 about Hillary, you know, “I cross my legs whenever I see her,” all kind of crazy things, because they, perhaps when they saw a powerful woman, they felt regressed to childhood, even if they didn’t understand why.

To what extent do you feel that women should vote for women whenever possible?

First it has to be a woman who supports other women, and that’s not always true. It wasn’t true of Sarah Palin, and it’s not true of Carly Fiorina. It wasn’t true of Margaret Thatcher. So it’s about substance and consciousness. However, there is something very important about having lived as a female human being, an African American female human being, a poor human being, a gay or lesbian or transgender human being. You know a reality that other people may not. So you can be very, very helpful and important in political office.

What would you say to Democratic women who don’t plan to vote for Clinton?

I would say, first of all, “It’s your right, I support you.” And second, “Think about why. If it really is about issues, fine. But if it is related in any way to the fact that she is a female human being, think about it.”

Are there any social justice issues today that you see as being intrinsically more about gender than they’re currently presented?

Oh, yes. Because I fear that the social justice movements are still perceived as if they’re in silos, as if they didn’t affect everything else. We talk about economic stimulus, by which we mean subsidies for banks and so on. Actually, the single biggest and most important economic stimulus would be equal pay for women of all races, which someone has kindly figured out would mean $200 billion more in the economy every year. It also would mean saving tax dollars since female head-of-households are more likely to also include children who are poor and who need government programs.

Police brutality often affects young black men, and the perpetrators are also often men. But do you think gender plays a role?

Yes, I do, absolutely. First of all, it plays a role in not paying enough attention to the women who have been brutalized by the police. There are crimes against women and probably disproportionately women of color that are sexualized and therefore somehow not counted. But in prisons, for instance, there was recently the case of a black woman who died in her prison cell. So I think we’re not looking at the reality of everyone affected by police brutality, but there is a deeper relationship, because among the biggest and perhaps the single biggest determinant of whether someone is violent is whether they grew up in a household with domestic abuse, and especially if they perpetuated that abuse themselves. For instance, think about Zimmerman and Trayvon Martin. Zimmerman had been previously [accused] of domestic abuse, after he murdered Trayvon Martin he was [accused] once or twice again. [He was acquitted of murder in the Martin case.] Yet the domestic abuse wasn’t even admitted in court. If we took domestic abuse seriously, Trayvon Martin might be alive. So this is deeply connected, and by discounting violence against females, you produce men who continue to commit what I think of as supremacy crimes—that is, they’re not going to get rich from these crimes, they’re about control. So the male dominant impulse to control women and the white dominant impulse to control people of color are very related in the same people.

Do you think having more women on the force would change things?

Yes—thank you, because when I read the stories about how the police force should reflect the city or the neighborhood, I have not seen it say it should be 50% women. They talk about representing racially and ethnically and I’m glad that they do, but how about women? It’s long been proved that women, not because we’re better human beings, necessarily, but when we arrive on a scene of violence or a criminal act, our arrival doesn’t escalate the situation. The arrival of men sometimes does. I have a friend who volunteers as a mounted police officer in Central Park, a woman, and she was talking about an incident in which her partner, a mounted policeman, was not able to negotiate—he was able to give orders, but not negotiate, and so sometimes increased the tension or the violence.

What do you think was a more important moment for social justice: now or the 1960s?

That’s an interesting question. You know, it’s not a competition, it’s a sequence. I think the ‘60s began the consciousness change, it began our knowledge that the current structure wasn’t just or inevitable. However, the ‘60s were not a majority movement—it was a smaller percentage of people who were active. Now the movements are majority movements, whether they’re about global warming or against racism or for marriage equality, obviously equality for women. We have an extremely imperfect democracy, to put it mildly, so the issues aren’t as far along as they should be, but if you look at public opinion polls, they are majority issues. And that’s very different from the ‘60s.

What do you want your singular achievement to have been?

I would just like people to think that perhaps I had left the world a little kinder and more just than it was when I arrived.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- How Canada Fell Out of Love With Trudeau

- Trump Is Treating the Globe Like a Monopoly Board

- Bad Bunny On Heartbreak and New Album

- See Photos of Devastating Palisades Fire in California

- 10 Boundaries Therapists Want You to Set in the New Year

- The Motivational Trick That Makes You Exercise Harder

- Nicole Kidman Is a Pure Pleasure to Watch in Babygirl

- Column: Jimmy Carter’s Global Legacy Was Moral Clarity

Contact us at letters@time.com