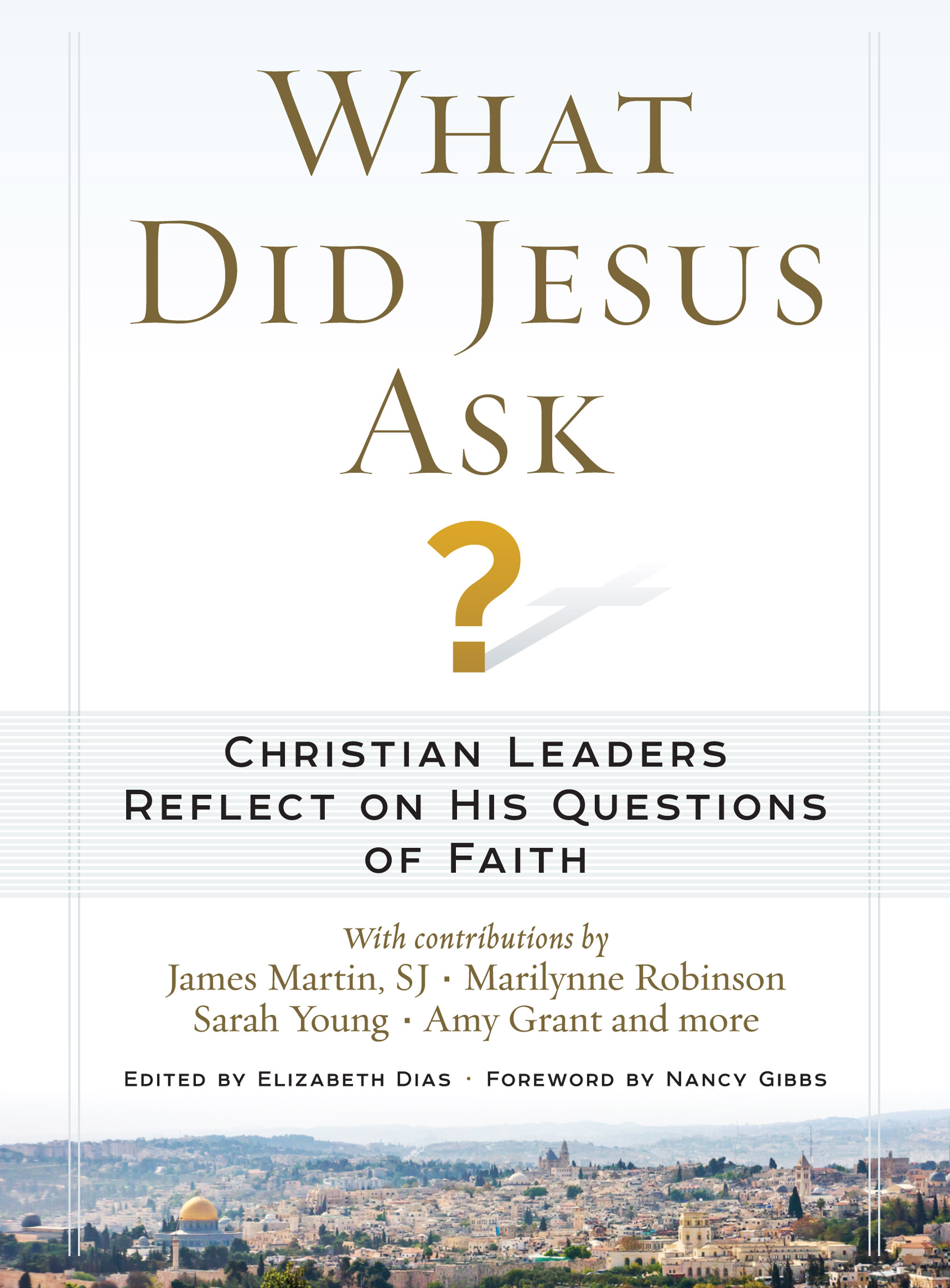

The following is an excerpt from What Did Jesus Ask?, edited by Elizabeth Dias and published by TIME Books, available from Amazon or Barnes & Noble. Read other excerpts from the book here.

“Why all this commotion and wailing?”—Mark 5:39

It is a rare moment when all three of them are yelling for something at the same time. Ozzie—named after the fiery evangelist Oswald Chambers—is still in a bellowing stage. The twins, Desmond and Anna, tend to plead their cases with me like I am judge and jury with their voices increasing in volume as they make their demands. I get whiplash from trying to make sense of their jumbled words and Ozzie’s periodic yelping as he gets a word in edgewise. When all three go at it I feel like I’m in a bizarre chamber of horrors. I can run, and I can hide, but unfortunately not for long. They always, always find me.

The commotion of our daily lives—it’s rooted in the arbitrarily popular-for-three-seconds toys and natural assertion of human bodies to carve out space whether they are 3 ft. tall or 6 ft. 3 in. like my husband Andy. I find myself flailing in this cramped space, arms and legs churning wildly in this storm, my head jouncing above and below water. Sometimes I take refuge in the bathroom. I need somewhere to breathe in and out hard. Or the laundry room. Usually the kitchen. My laptop is set up on the counter next to half-eaten apples and sippy cups tacky from juice. I peruse all manner of social media for stories about the outside world. I come across images of crowds filling the streets in Ferguson, Mo. A different kind of commotion, and one that shifts my perspective in those brief moments.

My head snaps up as the children protest my lack of providing “fair” judgment when it comes to whose turn it is to play with the plastic, much too lifelike frog or Thomas the Tank Engine. A wailing ensues that threatens to drown the last of my brain cells, obliterating any ability to make a clear decision. I despair a little trying to imagine how I might possibly provide them with a reasonable perspective. I’m overwhelmed, for these people have reasons for making noise.

I read Mark’s telling of the story of the hemorrhaging woman and Jairus’ daughter and feel a bit of mental commotion. I see a provocative mingling here—an old woman with a persistent blood disease and a prepubescent girl on her deathbed. Still, both are in need of Jesus’ touch, whether to touch or to be touched by a power that gives life, and not only new life but a touch that gives life back.

I ponder their bodies. The woman who was likely deemed untouchable—physically, socially and emotionally—and who was in major isolation because of the impurity of this persistent bleeding. It is unholy and unclean, and she knows it. I wonder, Where is her family? Does she have a husband or children? What would it be like to not touch them or be touched by them for 12 years? What would it be like to not have children running between her legs or entreating her to sit so they can dog-pile her for an hour even though there are plenty of seats elsewhere, for the sole purpose of being near her? What would it mean to get my life and my body back so I could feel the butterfly kisses of my children and the embrace of my husband or parents?

Jesus healed her without being conscious of it. When she touched him, he noticed something had changed in him. I am moved by the way this woman’s touch moved him. I want to play with the possibility that it even transformed him. He affirms her faith, and in doing so he affirms her agency and recognizes her will toward life. And we see here a picture of Jesus, his body, his potential for miraculous connection and even conversion.

On the other hand, Jairus’ family, overcome with grief, laugh derisively at Jesus when he says the little girl is not dead but only sleeping. Undaunted by their perspective, he heals her, and she gets up to walk around, shaking the sleep out of her limbs as if she were waking up for breakfast and getting ready to head off to school. I wonder if the daughter was even aware of her death, if she was confused at all by the tears of surprise and relief of her family. Did Jairus sweep the little girl up into the air? Did her mother cover her with kisses of grateful disbelief? Did she pull her daughter close, smelling her hair, feeling her breath on her face, her fingers around her neck and her warm blood pulsating beneath her skin, pumping hard from a strong heart?

My mind shifts to Ferguson and the videos of Lesley McSpadden after the grand-jury decision not to indict Darren Wilson for the murder of her son Michael Brown. I watch her body crumple to the ground. She lifts up her face to the sky, and her mouth is contorted in agony, her cheeks covered in tears. Her voice keening, she is wailing, and I can feel it reverberate across my own flesh and blood, in my skin and marrow—the loss of life and the loss of justice. I see the streets of New York City, Chicago, Detroit and even Bloomington fill up with people of all colors marching with signs that say #blacklivesmatter. The people walk together like resistance is the new air, we breathe it, and I look at my little girl Anna next to me holding her sign. Before we leave to go home for dinner and baths, we stand with the group for 41⁄2 minutes in silence to remember Michael Brown’s body dead in the street for 41⁄2 hours. The red and blue lights of police cars in my eyes and cars rushing by on the other side of the street—I weep a little and breathe out, “Lord Jesus, hear our prayer.”

Anna is on my back in the baby carrier. She is asleep but begins to wake up, softly crying over and over, “Mommy, Mommy, Mommy …” My heart falters at the thought of the cries of the men and women lying in the streets—someone’s babies—and how they went unheard and were silenced by violence and death. I think about the strangled noises of life leaving bodies that were brutally shot or killed with bare hands. I think about mothers and fathers collapsing to the ground wailing for lost children. I think about suicide bombers and school shootings and massacres and buildings falling on top of people—lives, voices, bodies.

Why all this commotion and wailing? It feels rhetorical. Come, Lord, Jesus, come quickly.

Mihee Kim-Kort is an ordained minister in the Presbyterian Church (USA) and the author of Making Paper Cranes, Streams Run Uphill and Yoked: Stories of a Clergy Couple in Marriage, Family, and Ministry.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com