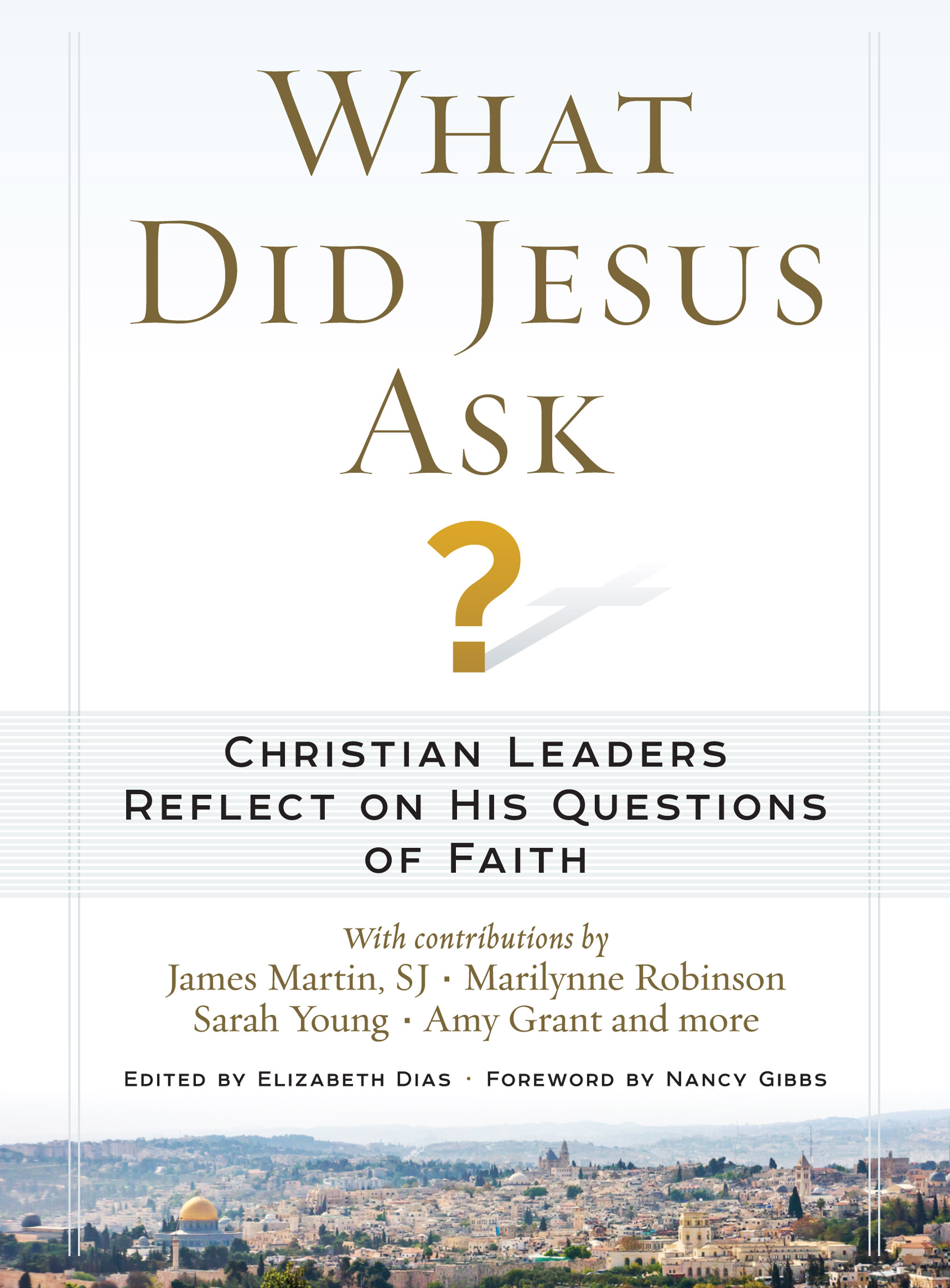

The following is an excerpt from What Did Jesus Ask?, edited by Elizabeth Dias and published by TIME Books, available from Amazon or Barnes & Noble. Read other excerpts from the book here.

“Do you believe that I am able to do this?”—Matthew 9:28

The most difficult question that the modern, rational, intelligent person can ask about the Gospels may be this: How can I believe that these things really happened? This, in essence, is the question that Jesus poses in the Gospel of Matthew to two blind men who ask Jesus, in so many words, to be healed: “Do you believe that I am able to do this?”

Jesus’ question comes in the middle of a rapid-fire series of four different healings in Matthew’s Gospel. A woman who had been suffering from internal bleeding for 12 years secretly approaches Jesus in a crowd, touches the hem of his garment and is cured of her affliction. Immediately afterward, Jesus enters the house of a synagogue official whose daughter is thought to be dead and says to the crowd, “The girl is not dead, she is only asleep.” After the crowd laughs at him, Jesus enters the house and either heals the girl or restores her to life. Then comes the story of the two blind men, and after that, Jesus heals a man who is “possessed by a demon.”

It’s not surprising that the crowds say, “Never has anything like this been seen in Israel!”

But again the question is: How can I believe these outlandish stories?

Many people see Jesus of Nazareth as a wise prophet, a compassionate teacher and an inspiring leader but stop short of believing him to be divine or possessing any supernatural powers. So they often set aside the miracle stories.

Yet the statement that Jesus acted as a healer and exorcist has as much reliability as almost any other statement that we can make about Jesus of Nazareth. In fact, those stories have more corroboration—that is, they are repeated and referred to in a variety of places throughout the Gospels—than do many other statements about Jesus that people often take for granted. Moreover, a great many of Jesus’ best-known sayings and teachings, which we also take for granted, are set in the context of healings and exorcisms.

Of course in Judaea and Galilee in the 1st century, physical illnesses were sometimes conflated with demonic possession. When Jesus cures a boy with epilepsy, for instance, different Gospels describe the boy as either suffering from epilepsy (literally in the original Greek: “moonstruck”) or being afflicted by a “spirit.” The Gospel writers were not modern-day diagnosticians, so it is sometimes unclear if some of the illnesses were psychosomatic in nature.

But many of the illnesses described by the Gospel writers are clearly not psychosomatic. Leprosy (which encompassed a variety of skin conditions), blindness, withered limbs and so on cannot be attributed to something that is in one’s mind. And whether or not people thought some illnesses were the result of demons, the point is that Jesus heals people from serious and sometimes lifelong afflictions—and does so immediately.

In other words, there is a reason the crowds are continually “amazed,” as the Gospels say. Even his disciples, no matter how many times they witness a cure, are “astonished.” “We have never seen anything like this!” they say after he heals a paralyzed man in Capernaum, a town by the Sea of Galilee.

The fact that Jesus healed people was never a source of controversy in his lifetime. Not even his fiercest opponents doubt that he performed miracles. The controversy is over when he does them (on the Sabbath, for example, which incurs the wrath of some of the Jewish leadership) and the source of his power (as when some of his opponents accuse him of deriving his power from Satan). Again, the healings are an essential part of Jesus’ public ministry.

Nonetheless, many people avoid, downplay and even ignore them. Why? They disturb us. Thomas Jefferson went so far as to scissor out all the miracles from the Gospels to create his own story of Jesus. He wanted a Jesus who didn’t threaten, a Jesus he could tame. Yet if we cut out the miraculous from his life, it’s not Jesus we’re talking about any longer. It’s our own creation.

The objection that Jesus could not do miracles may come from the same reasoning that says that God does not exist, or if God does exist then God is not all-powerful. Even devout Christians may play down the miracle stories as a way of making Jesus more “credible” for modern-day audiences. For instance, preachers and homilists will often say that the miracle of the multiplication of loaves and fishes, when Jesus fed a vast crowd with just a small amount of food, was not a miracle per se. Rather, what happened that day on the shores of the Sea of Galilee was that the crowds shared what little food they had, and enough was provided for everyone.

Then the preacher will say, “And isn’t that just as miraculous as if Jesus had multiplied the loaves and fishes?”

To which I answer no. This easy-to-digest interpretation reflects the unfortunate modern desire to explain away the inexplicable and to downplay miracles in the midst of a story filled with the miraculous. Almost one-third of Mark’s Gospel, for example, is devoted to Jesus’ miracles. To my mind, some of the interpretations that seek to water down the miracle stories reflect unease with God’s power and Jesus’ divinity, discomfort with the supernatural and, more basically, an inability to believe in God’s ability to do anything.

It also is solipsistic. Such rationalizing explanations, which reflect a desire to explain away all that we cannot understand, are often based on a principle that can be summarized as follows: “What does not happen now did not happen then. If no one can cure a blind person now, then Jesus did not heal a blind person either.” It also suggests that historical events can and should be interpreted only through earthly cause and effect, with no supernatural explanation. Finally, it suggests that there are no unique historical figures. Such an approach reduces Jesus to the status of everyone else, when he was completely unique.

More basically, as I mentioned, it reflects a discomfort with Jesus’ divinity. But to me, the idea that the Creator of the Universe could enable his Son to heal illnesses is rather easy to believe. If you can create the universe from nothing, then healing a paralyzed man seems a relatively simple thing.

When Jesus asked the two blind men, “Do you believe I can do this?” he is implicitly asking us the same question—or questions: Do you believe that I am the Son of God? Do you believe that I have divine power? In short, do you believe that nothing is impossible with God? These are essential questions for anyone encountering Jesus in the Bible.

The blind men answered yes, and then they were able to see. We are invited to do the same.

James Martin, SJ, is a Jesuit priest and editor at large of America and the author of Jesus: A Pilgrimage.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com