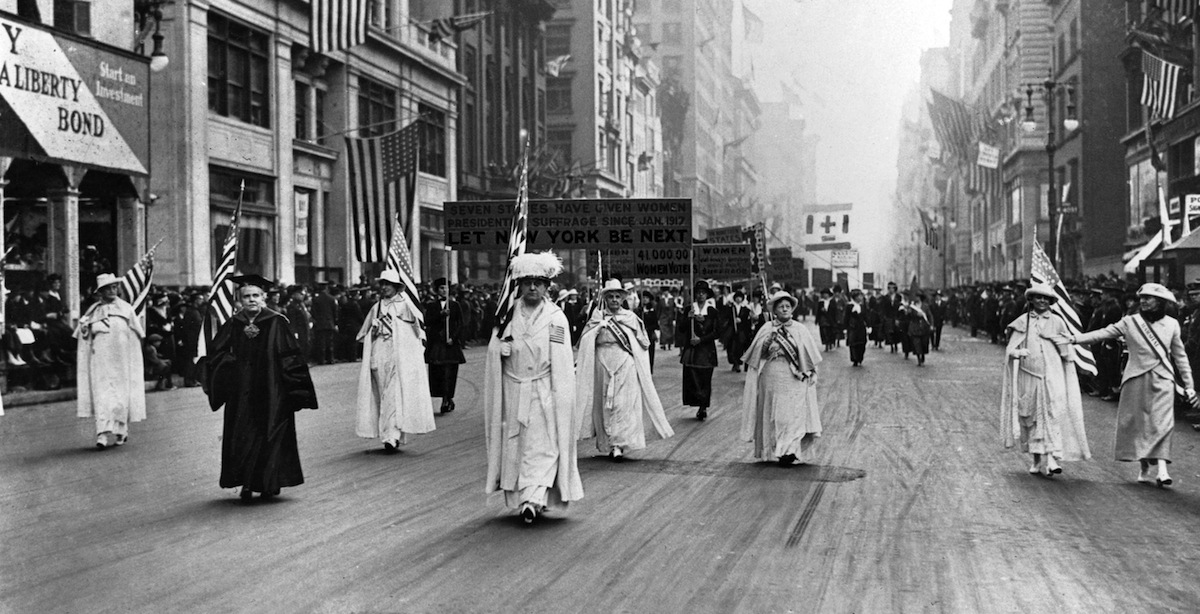

They came on horses and carriages. They marched on foot. There were old women with canes and young mothers with babies. They dressed in white and carried banners with phrases like “A vote for suffrage is a vote for justice” and “You trust us with the children; trust us with the vote.” It was Oct. 23, 1915, and tens of thousands of women flooded Fifth Avenue in a spectacular, five-mile suffrage parade that all but shut down New York City.

The parade looked triumphant, but was actually a fraught and nervous event. New York State was about to have a referendum vote on whether to allow women the vote. Women didn’t yet have the ability to vote nationally, but 13 states had already enfranchised women. Progressive New York seemed on the verge of changing its mind about whether women belonged in the polls. Despite signs of political progress, there was a lot riding on the assembly. Organizers knew the parade had to go off without a hitch to garner the needed support for the vote. This was the high-profile chance suffragists had been waiting for—but the march didn’t quite go as expected.

By this point, suffragists were tired of being portrayed as fire-starting militants and misguided housewives. This parade was their chance to showcase their beauty and appeal in what one historian would call a spectacle “as well choreographed and rehearsed as a Broadway extravaganza.” They gathered delegates from labor unions and suffrage groups from around the world. Line after line of women marched up the avenue, holding hands, festooned with garlands and flowers and hoisting huge signs. A highlight was a small group of women who carried ballot boxes on a stretcher.

And people took notice. “In golden sunlight and keen air the great parade went its triumphal way,” wrote The New York Times the day after the parade. Onlookers cheered endless rows of demure women in white dresses, “more poem than procession.” There was even a breastfeeding mother in the marching lines, a “fine Junoesque woman of the finest mother type” who was cheered by onlookers along the entire route.

But in a way, the very order and beauty of the parade backfired. Women reading newspapers in the days that followed were more likely to see coverage of things like the parade’s hats, costumes, dogs—confusion over whether dogs could march in the parade was apparently resolved the day before—and of the reactions of male onlookers than they were to find thoughtful conversations about whether it was time to give New York women the vote. One women’s-wear publication even focused on the marching women as shoppers, not legitimate protesters, explaining that “the ballot was uppermost, of course, but shopping rarely is far from a woman’s mind.”

The parade was the peak of a series of grand suffrage parades in the city—spectacles that had gone from boos, threats and police action to dignified, entertaining events that showed the might and maturity of a women’s movement that was ready to vote. Official counts of the parade ranged from around 25,000 to well over 60,000, with at least 100,000 spectators stepping away from work and play to acknowledge the sheer magnitude of the national movement for women’s rights.

In four years, the 19th Amendment would grant all American women the right to vote. But New York’s spectacular suffrage parade didn’t achieve its goal. Just weeks later, the referendum failed. It would be two more years before New York suffragists would manage to convince their fellow citizens to let them vote in their own state, but the parade left an impression on both the city and its onlookers. In the words of Henry J. Allan, a Kansas newspaper editor who watched the parade expecting to see a joke, “It was absolutely overwhelming. Forty thousand women do not spend days getting ready for a five-mile march through crowded streets, and hours marching in a raw afternoon, for a transitory whim. It was the most democratic exhibition I have ever seen in New York.”

13 Great American Suffragettes

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Inside Elon Musk’s War on Washington

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Cecily Strong on Goober the Clown

- Column: The Rise of America’s Broligarchy

Contact us at letters@time.com