For years, climate change activists have criticized the Canadian government as a global warming laggard. The Conservative Prime Minister Stephen Harper, who has been in power since 2006, has never taken climate change seriously. When Canada failed to meet carbon cuts set in the Kyoto Protocol—a treaty Canada signed and ratified under a previous government—Harper simply withdrew his country.

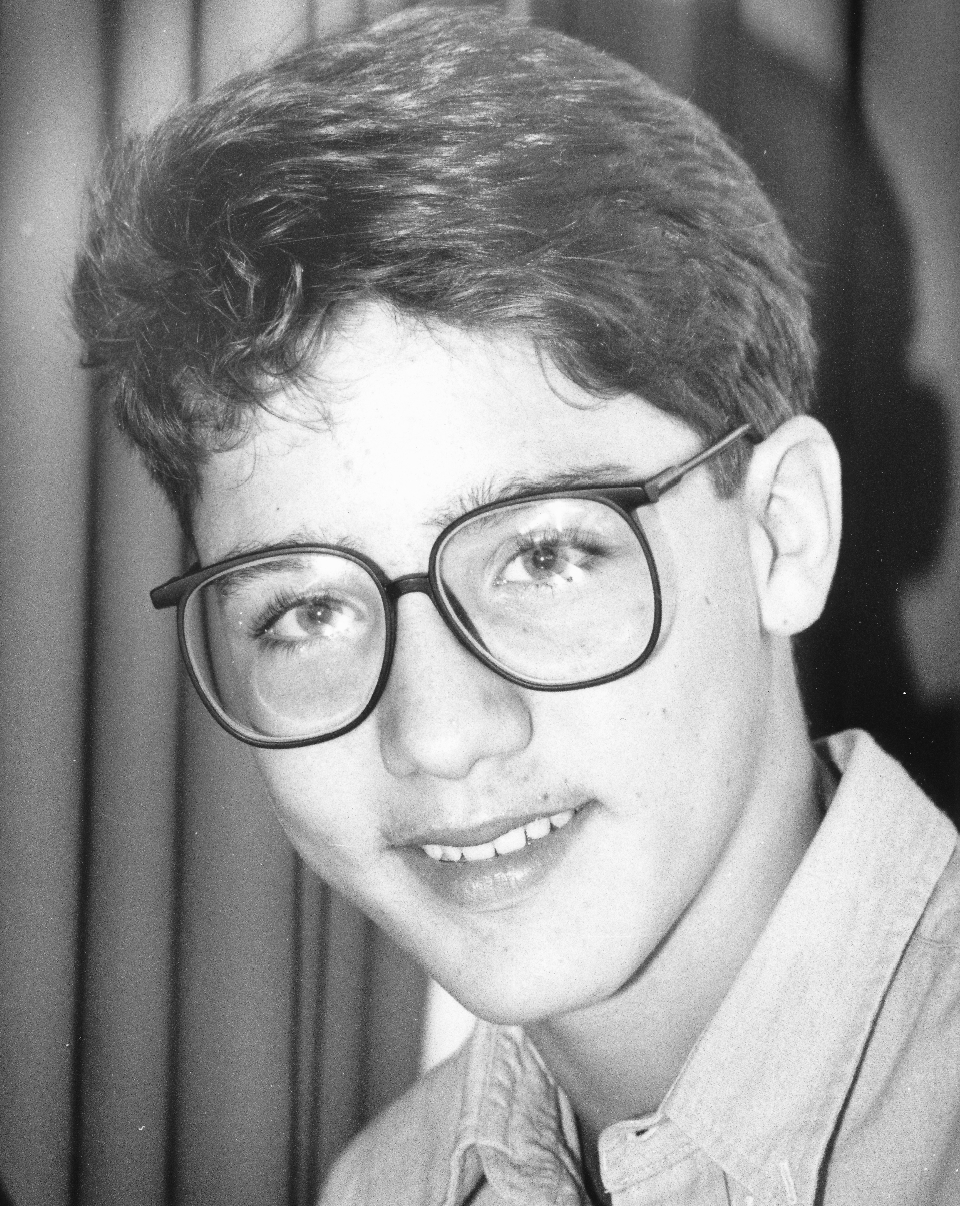

But the surprise election of Justin Trudeau yesterday promises to change that perception. The Liberal Party leader emphasized the very real danger of climate change and pledged his support for what he called a “pan-Canadian” approach to the issue. “In 2015, pretending that we have to choose between the economy and the environment is as harmful as it is wrong,” he said in a speech earlier this year.

Even with a resounding win, however, it may provide surprisingly difficult for new Prime Minister Trudeau to enacting strong environmental and energy policy at the federal level in Canada. Control over Canadian environmental and energy policy rests largely with the country’s powerful provincial leaders. Indeed, the country explicitly leaves authority over natural resource management to the provinces. And many Canadians still recall an ill-fated attempt in the 1980s by the federal government to grab a larger share of the profits from energy resources in individual provinces. That program was championed by none other then Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau, Justin’s father.

“Provinces have enormous authority in so many areas and there are huge regional differences on this issues,” said Barry Rabe, a professor of public policy at the University of Michigan. “Canadians have struggled mightily to put together a federal policy that address emissions.”

Read More: Why Restoring Nature Could Be the Key to Fighting Climate Change

For these reasons, Trudeau appears keen on implementing a carbon pricing scheme that would set targets for emissions reductions at the federal level and allow for provinces to design programs independently to meet those goals. The program, which still needs to be fleshed out, might bear some similarity to the President Barack Obama’s Clean Power Plan, said Rabe, which sets emissions reductions standards for each state based on its current energy sources.

Relying on sub-national governments to act also makes sense given what many Canadian provinces have accomplished already. Authorities in Quebec, the second-largest province in Canada, instituted a cap-and-trade program which allows for the trade of carbon credits with California. The west coast province of British Columbia has the country’s only carbon tax.

Trudeau’s victory comes just in time for a major United Nations meeting on climate change that begins next month in Paris. Under Harper, Canada declared that it would cut greenhouse gas emissions by 30% by 2030 from 2005 level—a commitment widely viewed as inadequate. Trudeau’s election won’t change that commitment given the short timeframe before negotiations begin, but the new Prime Minister has already said he plans to attend the conference along with the country’s provincial and territorial leaders, in a show of support for the international process.

Stronger climate action from Canada won’t stop globe warming on its own—the country emits only 2% of the world’s carbon emissions from the consumption of energy, according to the Union of Concerned Scientists, though it has one of the highest per-capita rates in the world. But experts say the defeat of a high-profile climate skeptic like Harper plays an important role in the global debate over climate change. Like other conservatives, Harper doubted that it was possible to take strong action on climate change without damaging his country’s economy. Low-income countries that wanted to drag their feet on climate change could always point to the example of high-emitting nations like Canada that refused to change their ways.

“It makes it easier for other nations of the world to shirk or not take action on this issue when they can point to Canada not really doing anything,” said Rabe. “Now the question is where does Trudeau fit in to all of this?”

See New Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s Life in Pictures

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Justin Worland at justin.worland@time.com