By now, GOP presidential candidate Carly Fiorina’s business record has been well parsed: As CEO of Hewlett-Packard in the late 1990s and early 2000s, she orchestrated the blockbuster merger with computer maker Compaq. She boosted short-term growth by cutting research and development, a hallmark of HP since its founding in 1939, and favoring areas like marketing instead. When things went south–some 30,000 employees lost their jobs as the company’s stock-market value was cut in half–Fiorina flew away in a golden parachute worth $21 million. As a result, she has been called, not entirely unfairly, the worst CEO in history.

Less well understood is the extent to which economic policy crafted in the Clinton era created careers like Fiorina’s, making her rise not only possible but also a reminder of how much the next President will have to fix.

Let’s start with pay. Pay packages of the kind enjoyed by top managers have been rising since the 1980s, which is also when stock buybacks became legal. Buybacks really took off in the 1990s, during President Bill Clinton’s much vaunted New Economy. Tech firms, many of which were run by his supporters, began lobbying against efforts to put into place accounting standards that would have forced companies to mark down the value of stock options on their books as an expense. One of the key reasons that buybacks burgeoned is that America’s corporate executives were allowed to buy company stock at below-market prices while firms pretended that nothing of value had changed hands.

A huge chunk of corporate pay is now awarded in stock–only about a third of executive pay is in cash. When the stock’s value rises, so do paychecks in the C-suite. That gives executives a personal incentive to do just what Fiorina did: make decisions that boost share prices in the short term, even if they wreak havoc with corporate well-being, jobs and long-term growth. As University of Massachusetts academic William Lazonick put it in a 2014 paper, “The toxic combination of stock-based executive pay and open-market stock repurchases has contributed to not only the growing concentration of income at the top but also the failure of the U.S. economy to sustain existing middle-class jobs and create new ones.”

It’s hard to overstate how much perverse incentives encouraging bad corporate decisionmaking were exacerbated by decisions taken by the Clinton Administration. Robert Rubin (who served as both Treasury Secretary and head of the National Economic Council) and Larry Summers (his deputy, who succeeded Rubin at Treasury) favored regulation allowing greater corporate compensation, much of it paid out in opaque ways, as well as tax breaks for the rich.

There were a few, like Joseph Stiglitz (the former head of the President’s Council of Economic Advisers), who were concerned about income inequality. That’s one reason back in the early ’90s, in response to the growing debate about the divide between CEO pay and what the majority of American workers took home, legislation was introduced that would limit the tax-deductible portion of CEO compensation to $1 million. To get around that cap, Rubin and others wanted an exemption for “performance-based” pay, which on Wall Street and in corporate America was typically awarded in options. The loophole camp prevailed.

Stiglitz now views this as one of the most problematic legacies of Bill Clinton’s tenure. The tax code, which was relaxed to favor corporate debt over equity, only encouraged more. “The whole stock-options boom caused so many incentives for bad behavior of all kinds, and for making each [corporation] look better than it was. It’s all directly responsible for what I’d term ‘creative accounting,’ which has had such a devastating effect on our economy,” he says.

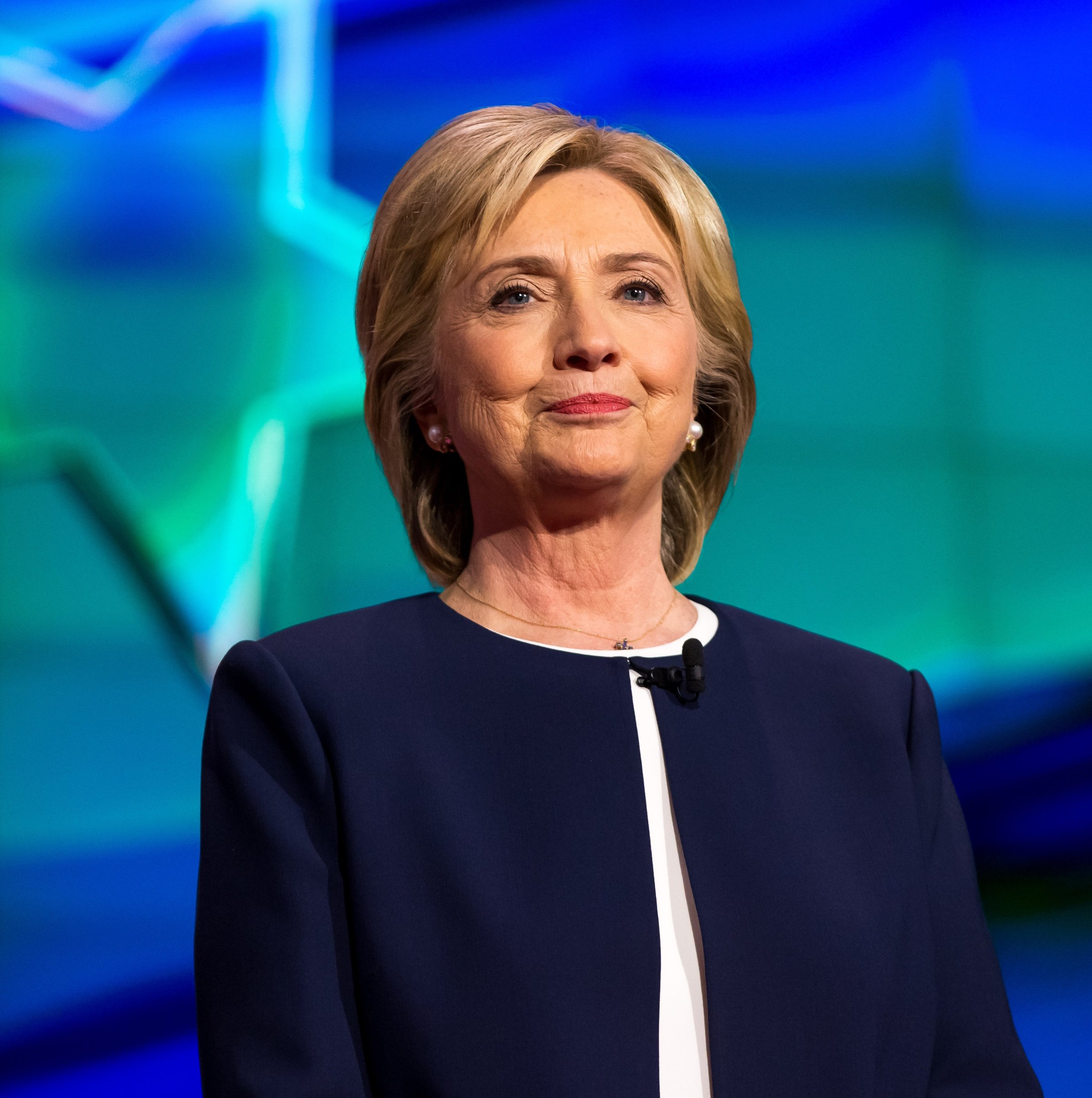

All of which creates some difficulty for the Clinton currently running for President. Hillary, who would like voters to remember the period of prosperity before 2001 fondly, was not making economic policy in her husband’s White House. And, as a candidate, she has decried “quarterly capitalism” and called for companies that do buybacks to announce them more frequently than once every three months. Her recent plan to curb Wall Street is an indication that she’s trying to move away from the legacy of the go-go 1990s (and appeal to the Bernie Sanders crowd).

Still, she doesn’t go far enough. If Clinton really wants to convince the left that she’ll be tough on Wall Street, she’s going to have to be a lot more specific about what she’d do to right the perversions that have warped American capitalism. If she doesn’t, she risks enabling more people like Fiorina–the 1% who have benefited so richly from her husband’s economic legacy.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com