Once the foundation of popular diet programs and nutrition guidelines, calorie counting has fallen out of favor with food experts. From a basic accounting standpoint, “calorie counting simply can’t be done accurately,” says Dr. Marion Nestle, a professor of food and nutrition at New York University and author of Why Calories Count.

For one thing, calorie counts listed on nutrition labels aren’t always precise for packaged foods. According to the FDA, a calorie value is only out of compliance if the actual number of calories the food has is 20% higher than what’s on the label. Even if you could rely on those calorie counts, trying to gauge how many you take in and expend each day is nearly impossible, Nestle says.

Mathematical hurdles aside, many nutrition researchers now argue that calories aren’t worthy of your attention. In fact, some eschew the term “calorie” altogether because it has become so fraught with incorrect or damaging connotations about diet, nutrition and health.

“If you come into our clinic and say the word ‘calorie,’ we throw you out,” says Dr. Robert Lustig, director of the Weight Assessment for Teen and Child Health (WATCH) Program at the University of California, San Francisco. Lustig is also author of Fat Chance: Beating the Odds Against Sugar, Processed Food, Obesity, and Disease.

You Asked: Your Top 10 Health Questions Answered

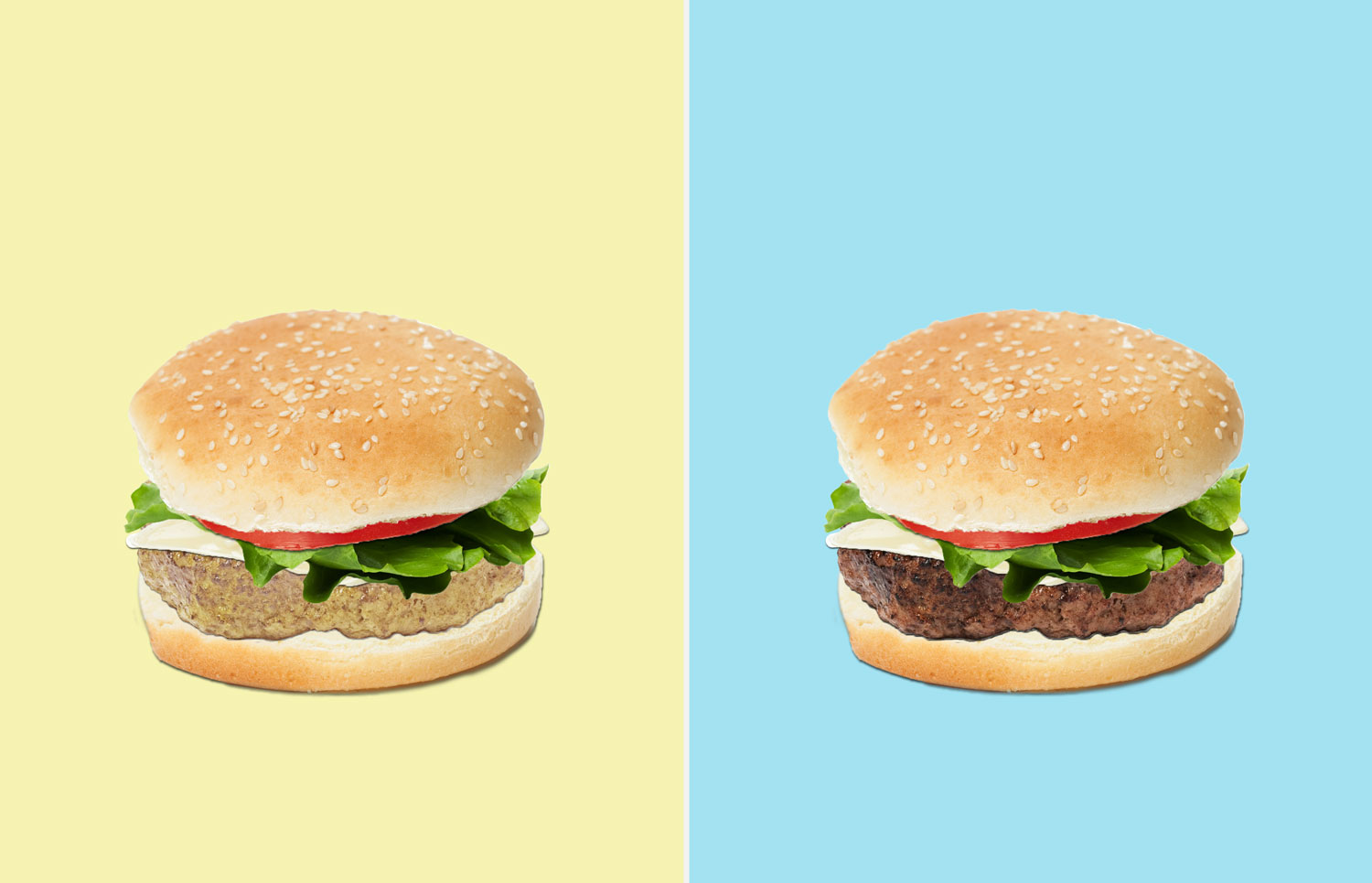

The problem with obsessing over the C-word, Lustig says, is that you’re ignoring biochemistry and buying into the misconception that all calories are equal. They’re not. “Different foods are metabolized differently, absorbed differently, converted into fat or energy differently and raise or lower your risk for disease differently,” he says. Focusing on calories ignores all of this complexity.

Lustig and other experts also take issue with the old “calories in, calories out” approach to weight loss. “People think overeating makes you fat, when really it’s the process of getting fat that makes you overeat,” says Dr. David Ludwig, a professor of nutrition at the Harvard School of Public Health.

Ludwig’s forthcoming book, Always Hungry, unpacks and refutes many of the damaging misconceptions people have about calories and weight management. “When you’re gaining weight,” he says, “something has triggered your fat cells to store too much energy, which doesn’t leave enough for the rest of the body.” That “something” is often the hormone insulin. When your body’s insulin response is out of control, “cutting back on calories can make the problem worse,” Ludwig says.

On the other hand, eating the right kinds of foods can temper your body’s insulin response and cause fat cells to settle down. “The cells open up and release their energy, which floods back into the body,” Ludwig says. “Hunger decreases, metabolism speeds up and weight gain isn’t a struggle because you’re working with rather than against your body.”

In other words, dieters have been preoccupied with quantity when we should have been focused on quality.

“The quality of our calories, meaning the types of food we eat, has an important effect on whether we gain or lose body fat,” says Dr. Walter Willett, who chairs the Department of Nutrition at Harvard. “Some foods leave us more satisfied than others, and also the insulin response to foods can influence how we metabolize or store these calories.”

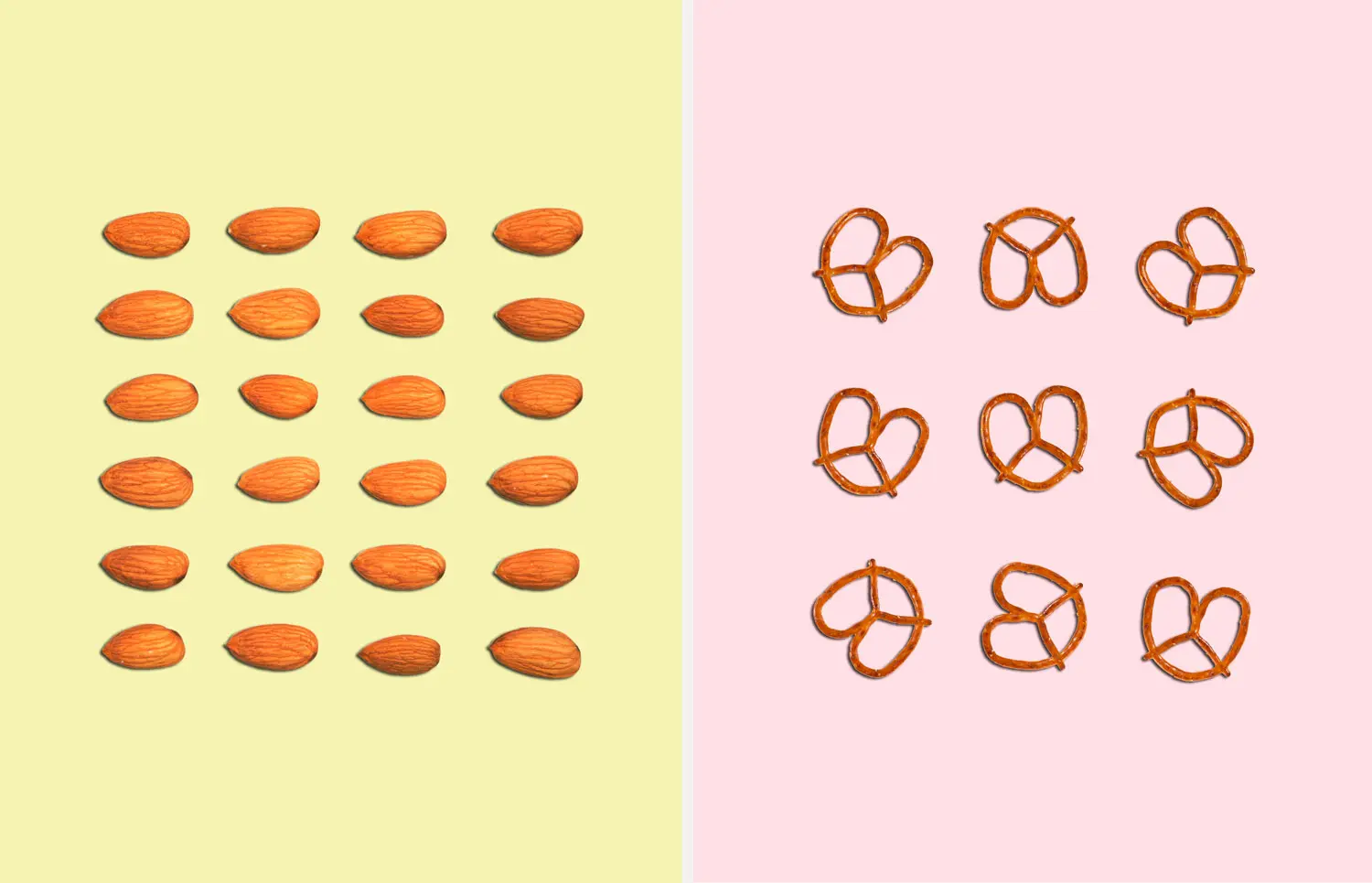

Along with Willett, both Lustig and Ludwig single out refined carbohydrates—most snack foods and packaged products, and especially sugar—as the principal drivers of the unhealthy insulin responses that fuel weight gain. Regardless of their calorie counts, “foods that raise insulin are the ultimate fat cell fertilizer,” Ludwig says.

At the same time, whole and unprocessed foods—including many that are fatty and calorie dense—mellow the insulin response and counteract weight gain. “It’s no coincidence that obesity exploded as we’ve cut back on fat and replaced it with sugar and starch,” Ludwig says. “The good news is it’s okay to eat lush, delicious foods that were once banished—things like olive oil, nuts, avocado, chocolate and even dark meat like chicken thighs.”

He adds: “Whole foods are inherently slow-digesting and don’t cause insulin to rise very much. Eating them is going to get you most of the way toward a healthy diet.”

The rest of us could do well by cutting the word “calorie”—but not calories themselves—from our mouths.

QUIZ: Should You Eat This or That?

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com