Europe has gotten used to eating China’s dust—economically, militarily, geopolitically. Now it appears Beijing beats Brussels anthropologically too. Never mind all that bragging Europe has always done about being the earliest cradle of modern humans—an honor it has shared with the Middle East. According to a new study just published in Nature, China wins at that game too—by a lot.

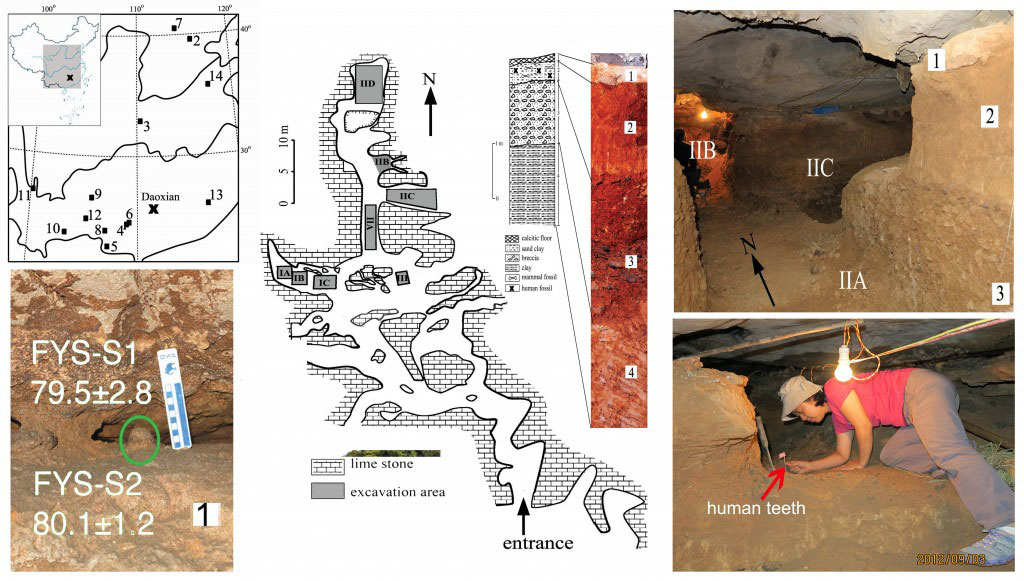

The announcement comes from a discovery made by a team of researchers—led by paleoanthropologist Wu Liu, of the Chinese Academy of Sciences—in Fuyan Cave in southern China. Despite its name, the Fuyan formation is not a mere cave, but instead a three-tier complex of caves, connected by tunnels. Together they comprise a volume of more than 100,000 cu. ft. (3,000 cu. meters). Over the course of two digging seasons, from 2011 and 2013, Wu and his team explored the chambers, exhaustively excavating all three.

The deepest one contained no remains of either humans or animals. The top one yielded a scattering of non-human mammal fossils. The middle chamber, however, was an archaeological jackpot. In addition to still more non-human mammals, that space also contained 47 exquisitely preserved teeth that were unmistakably human.

Finding early humans in southern China was not, by itself, an anthropological earthquake. Multiple migration routes can account for how homo sapiens first found their way there, including a route through Java, which was once home to homo erectus, one of many human ancestors. But those routes always put the homo sapiens‘ arrival in China at less than 45,000 years ago, after the species had already reached Europe. Uranium-thorium radiometric dating, however—the type typically used to determine the age of the calcium carbonate in teeth—puts the new fossils at somewhere between 80,000 to 120,000 years old, blowing the doors off the European date.

Dating the teeth was not the whole story, of course. It took human analysts to determine if they were indeed modern—and the evidence was overwhelming.

The Fuyan teeth are smaller than those of earlier humans, and much closer in size to those of fully modern homo sapiens. Grooves on the canines, premolars and molars, as well as characteristic bulging on the buccal—or cheek-facing sides—of the teeth, also put them squarely in the modern mold. The shape of their roots also distinguish the teeth from those of earlier humans as well as from Neanderthals.

Taken together, the researchers write, the analyses of the teeth are “the earliest and soundest evidence of definitely modern humans in southern China at least 80,000 years ago.”

While we know the humans found by Wu Liu’s team were modern chronologically speaking, the investigators reach no conclusions about how technologically advanced the Fuyan cave people were. The presence of so many mammal bones—38 species in all were identified—may suggest butchering, but no stone tools have been found so far. They also can’t say for certain why it took modern humans so much longer to establish a foothold elsewhere in the world. The Neanderthals, however, might be the answer, representing what the paper calls an “ecological barrier” to homo sapiens in Europe, competing for food and space and even breeding across species, entangling their genes.

It wasn’t until the Neanderthals were finally in decline that modern humans could fully thrive. China—then as now—might have simply turned out to be a bigger and more promising market.

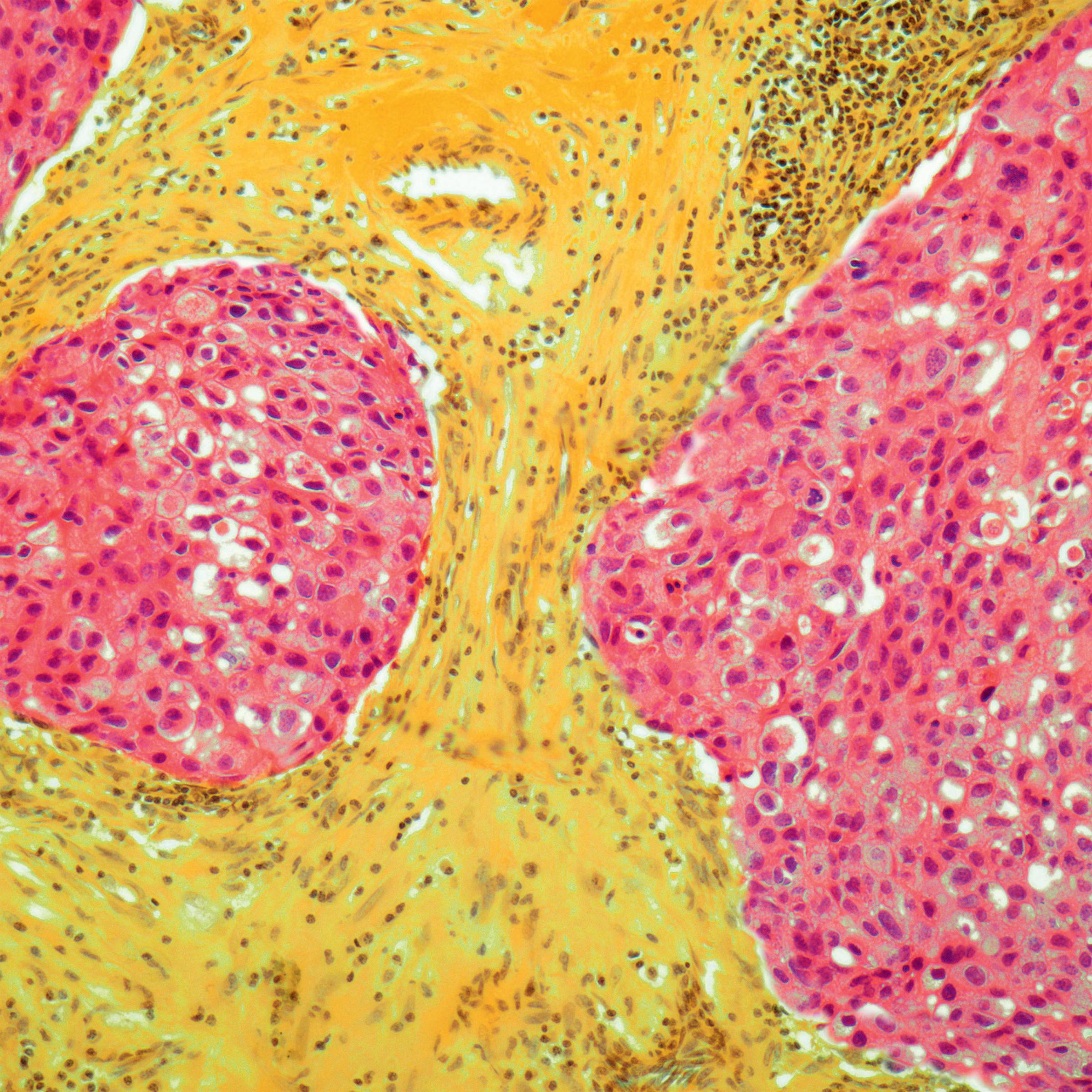

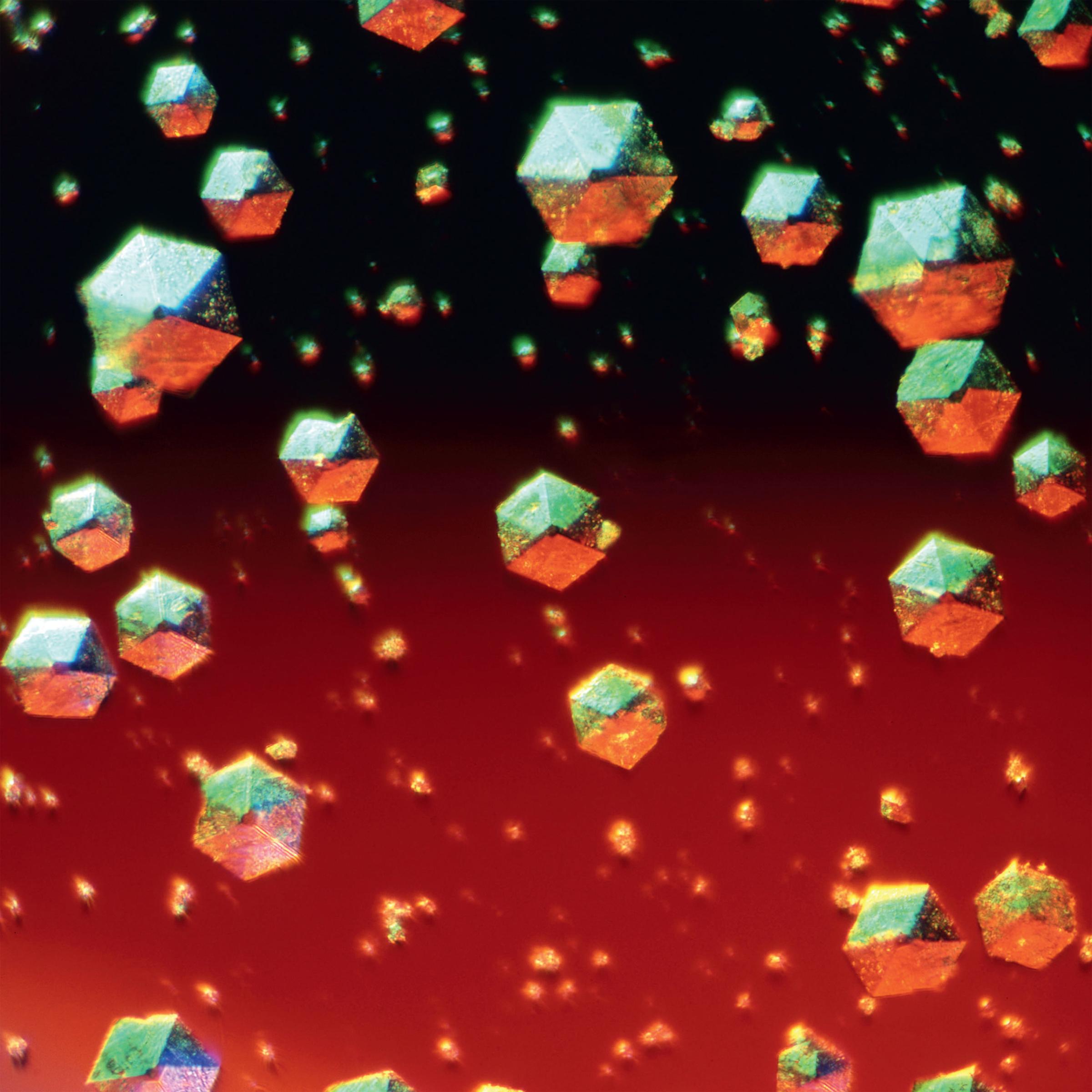

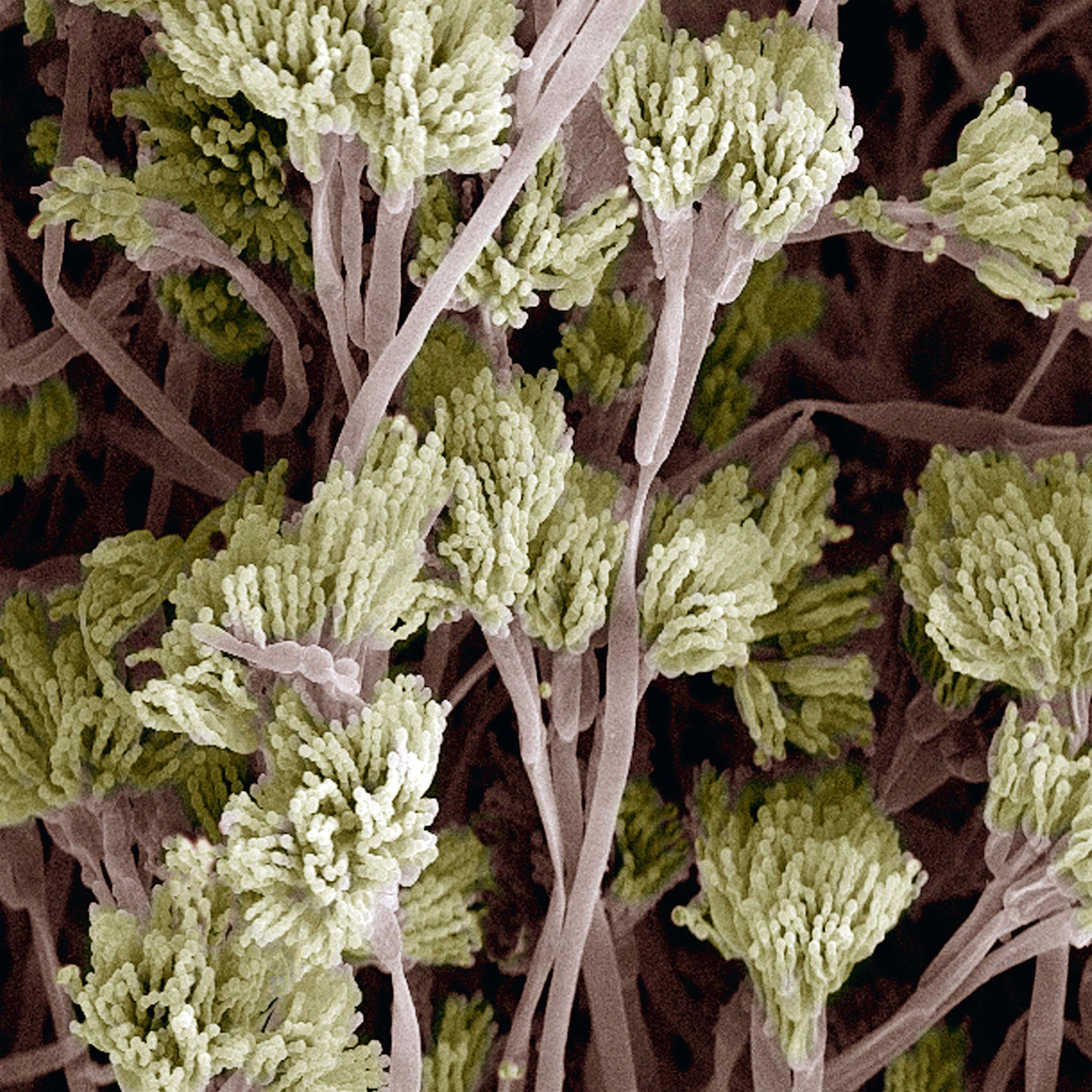

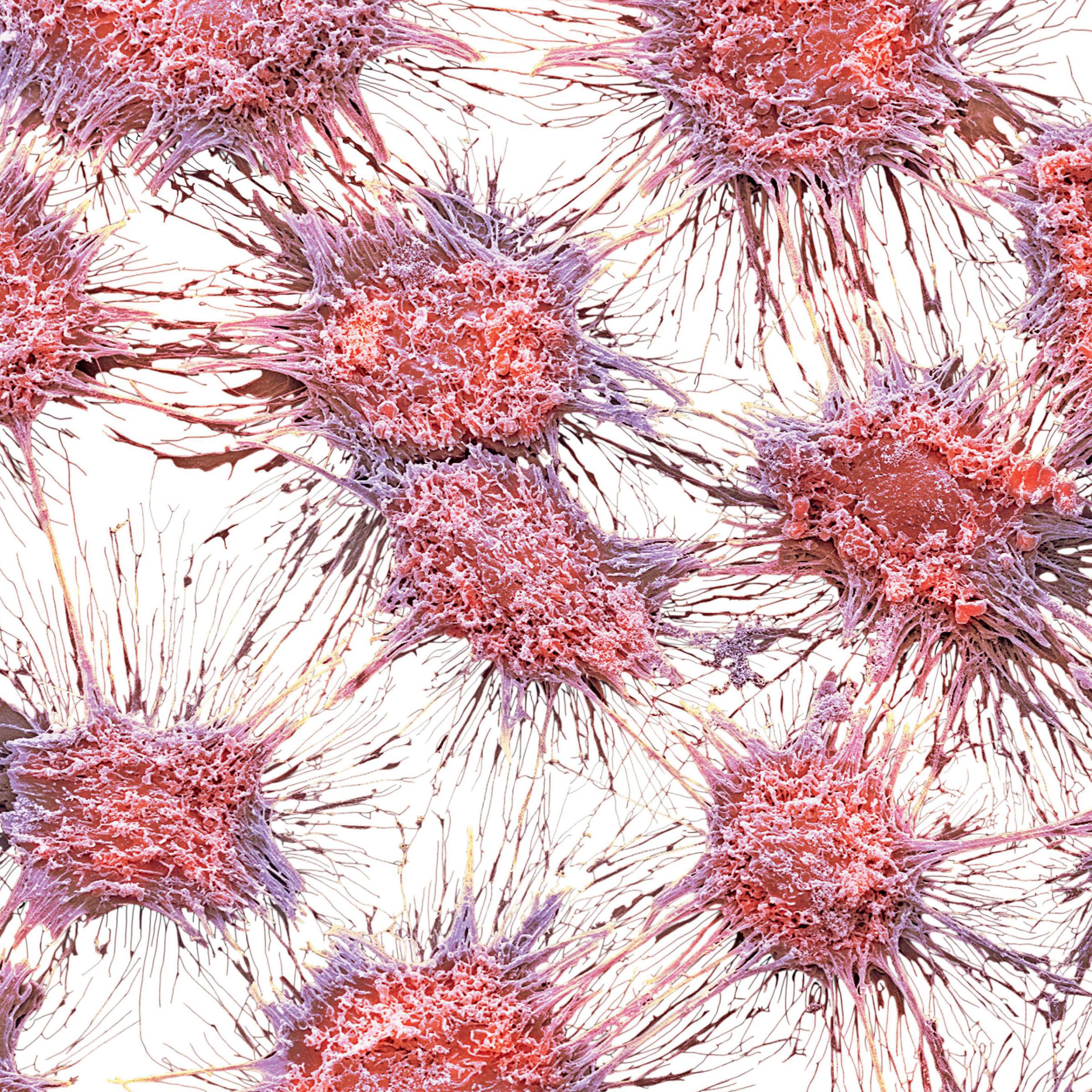

See the Human Body Under a Microscope

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Trump’s Message Worked on Latino Men

- What Trump’s Win Could Mean for Housing

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Sleep Doctors Share the 1 Tip That’s Changed Their Lives

- Column: Let’s Bring Back Romance

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Jeffrey Kluger at jeffrey.kluger@time.com