In July 1923, Leon Trotsky published an article in Pravda, Russia’s main, state-run newspaper, titled “Vodka, the Church, and the Cinema.” In it, he argued that cinema and movie-going culture would do for post-revolutionary Russia what taverns and churches did for Imperial Russia, only better. Like the tavern, the cinema would provide patrons with intoxicating, light-hearted amusement. Like the Orthodox Church, films screened in the cinemas of the future would teach the laity about morality and universal truths, all tailored according to new socialist norms.

Yet the cinema, Trotsky wrote, was a much more natural and “democratic” institution than the bar rooms and churches of the old regime, much more in tune with the diverse intellectual needs of the people, and workers in particular. “In church, only one drama is performed year in and year out,” he noted, “while the cinema next door shows pagan, Jewish, and Christian Easters.” Whereas taverns and churches served to distract and dull one’s conscience, the cinema, according to Trotsky, “amuses, educates, strikes the imagination with images, and liberates you from the need of crossing the church door.”

When the article was published, only a year had passed since the official end of the Russian Civil War, an extraordinarily violent conflict that exacted a large human and material toll on the young Soviet state. Though a worker’s paradise had seemed coherent in the minds of chief party theorists like Trotsky and his center-right counterpart Nikolai Bukharin before and during the civil war, building a communist heaven on earth during peace time was another issue altogether. The enthusiasm of the Bolsheviks and their leader, Vladimir Lenin, was dampened by the obstacles they now faced as the ruling party of the world’s first socialist state.

A complex and bitter debate coalesced within the Bolshevik Party in the early 1920s over the direction that the country should take. On the center-right stood Bukharin and his more conservative counterparts who favored a “retreat” to the pre-revolutionary status quo. Bukharin’s opponents on the left, led by Trotsky, envisioned a categorical break with the past, one that entailed a centrally planned, non-market economy and the end of private property. In this sense, Trotsky’s invocation of the cinema fit neatly into his larger policy agenda. Not only did the rise of cinema and the end of tavern and Orthodox culture represent a clean break with Russia’s imperial past, it also prefigured heavy state involvement in the country’s cultural, economic and social life. He reasoned that, like the Romanov family that profited from the sale of vodka, the Russian state would get rich through Mosfilm, the world’s largest film producer and distributor, dictating the industry’s content and scale.

Ultimately, Bukharin’s vision won out in the form of the New Economic Policy, one that called for a return to semi-capitalist practices like small-scale business ownership, private housing, and even religious observance that, to some (like Trotsky), represented a betrayal of the socialist ideals for which the Bolsheviks had fought. But when it came to revolutionary culture, Trotsky’s idea of a clear break from the past lived on.

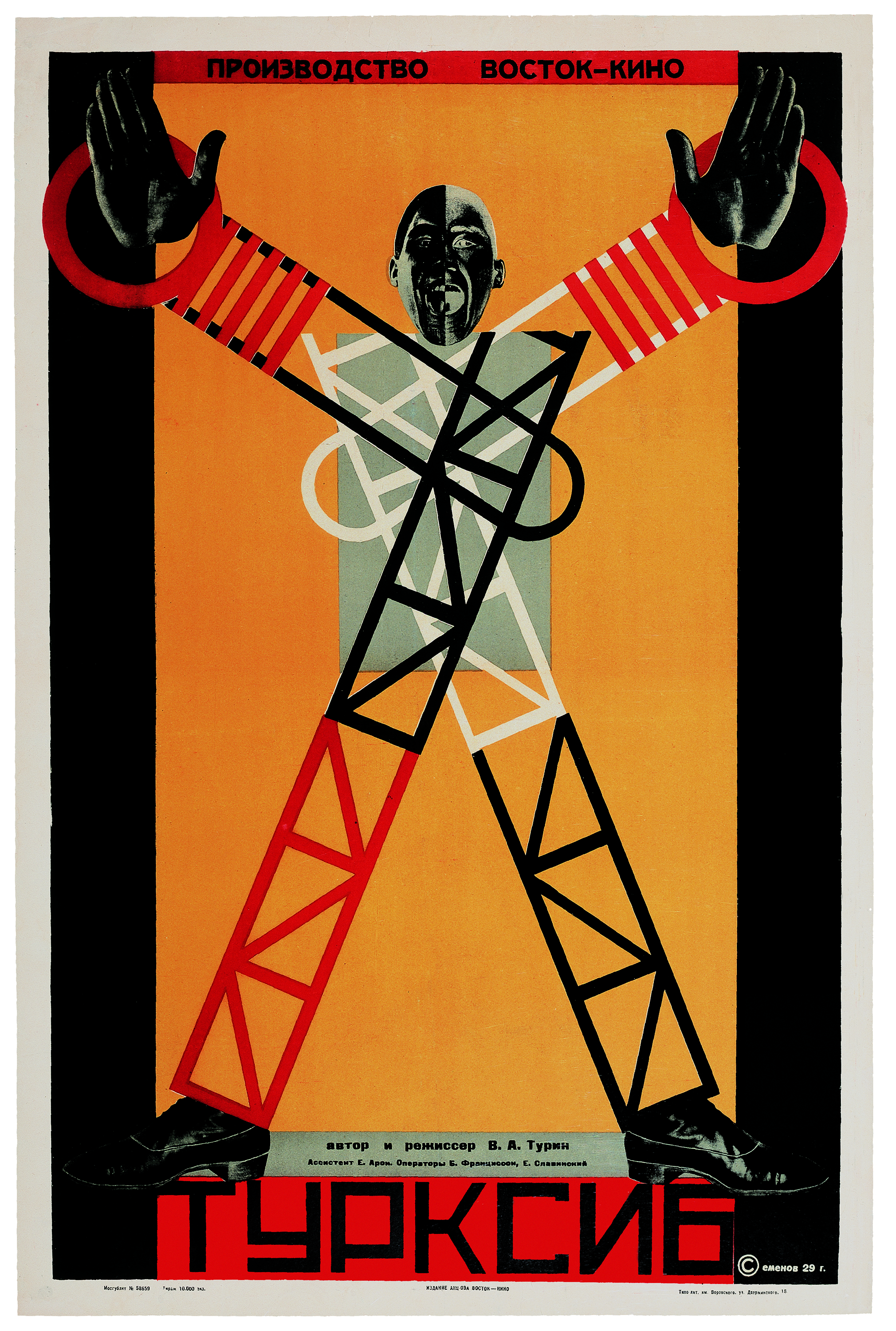

The Soviet Union during the 1920s became home to a robust and diverse avant-garde design movement, one that was committed to socialism’s promise of equality, modernity, abundance and individual liberation. Literary and visual artists like Alexander Rodchenko, Vladimir Tatlin and Vladimir Mayakovsky produced designs featuring abstract shapes, bold colors, clean lines and absurdist scenarios, a stark contrast to the realist aesthetic typical of the Imperial Russian regime. Constructivist architects like Konstantin Melnikov and Moisei Ginzburg built commercial and residential buildings that reflected radicals ideas about a future of large-scale communal living, where individual kitchens disappeared, children were raised by society, and the fruits of socialist labor were consumed by all. Perhaps ironically, forging a communist culture gave designers the opportunity to develop their own individual careers and artistic styles. Many exploited the revolution’s potential for creative destruction to forge and promote their own aesthetic brands, ones that they lent to various revolutionary media outlets including journal covers, advertising firms, photography exhibits and museums.

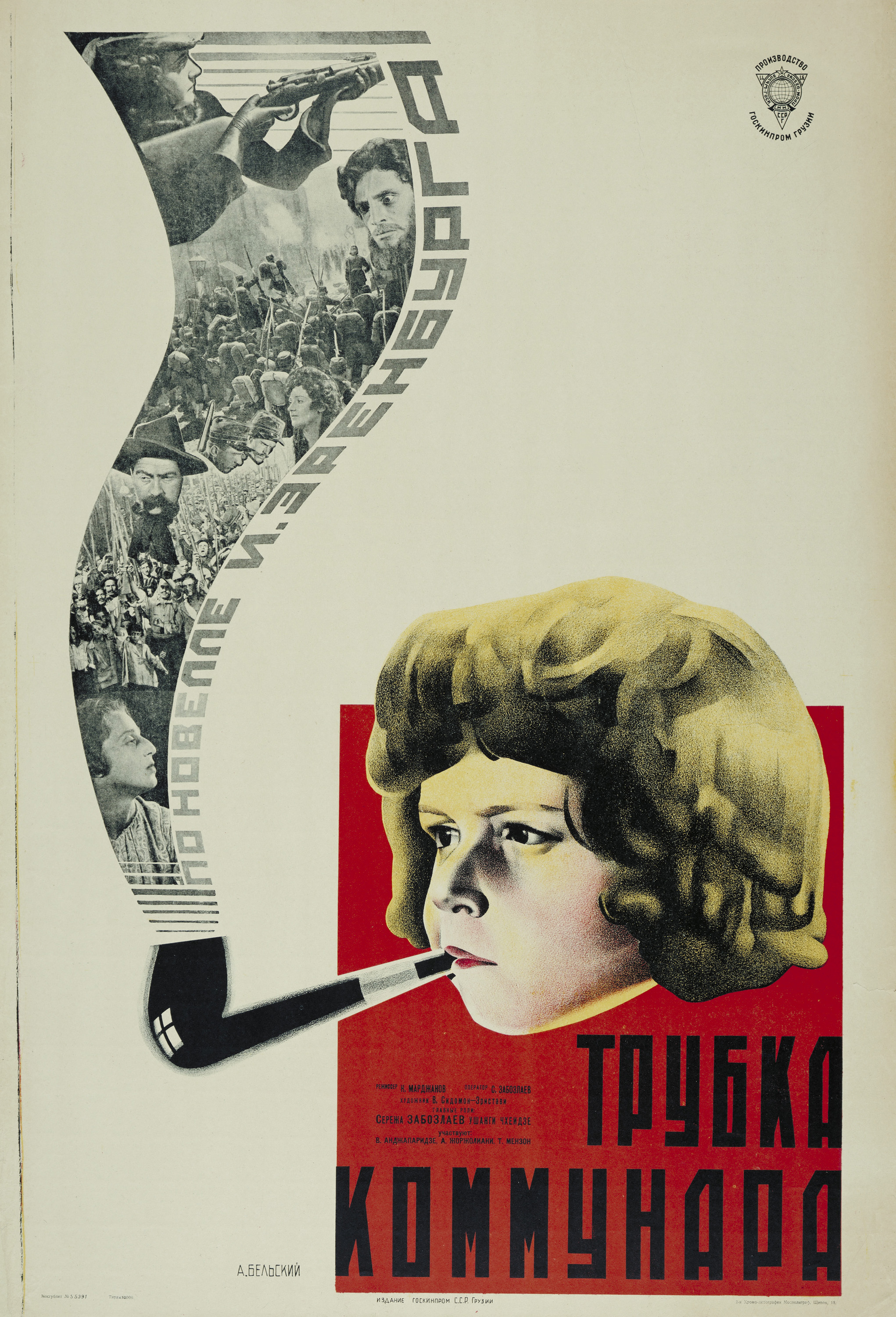

Avant-garde designers also mingled with and lent their skills to their counterparts in the Soviet silent film industry, and some of the resulting work can be seen in posters above, which are currently on view at the Jewish Museum in New York. Many of those designers were members of the editorial board of LEF, or Left Front of the Arts, the avant-garde movement’s main magazine. Indeed, poster commissions for films like Dziga Vertov’s Man with a Camera (1929) provided avant-garde artists with the ultimate challenge, that of communicating the contents of piece of art to a mass audience that remained unfamiliar with the genre to which that work of art belonged. Anton Lavinsky’s poster for Battleship Potemkin, Sergei Eisenstein’s 1926 film about the 1905 anti-tsarist sailor mutiny on the Imperial Russian ship “Potemkin” and the popular protests that followed, is a case in point. The artist’s use of familiar objects and linear shapes – sailor costumes, symmetrically angled canon cones – as well as the well-known date of 1905 made legible a kind of media that was still considered new in 1926.

In many ways, the poster exposes the enormity of the Bolshevik project altogether, whose goal was, as Trotsky hoped, to amuse, educate, strike the imagination, and liberate the Russian people, all at the same time and all at once.

The exhibition The Power of Pictures: Early Soviet Photography, Early Soviet Film is on view at the Jewish Museum in New York City through Feb. 7, 2016.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com