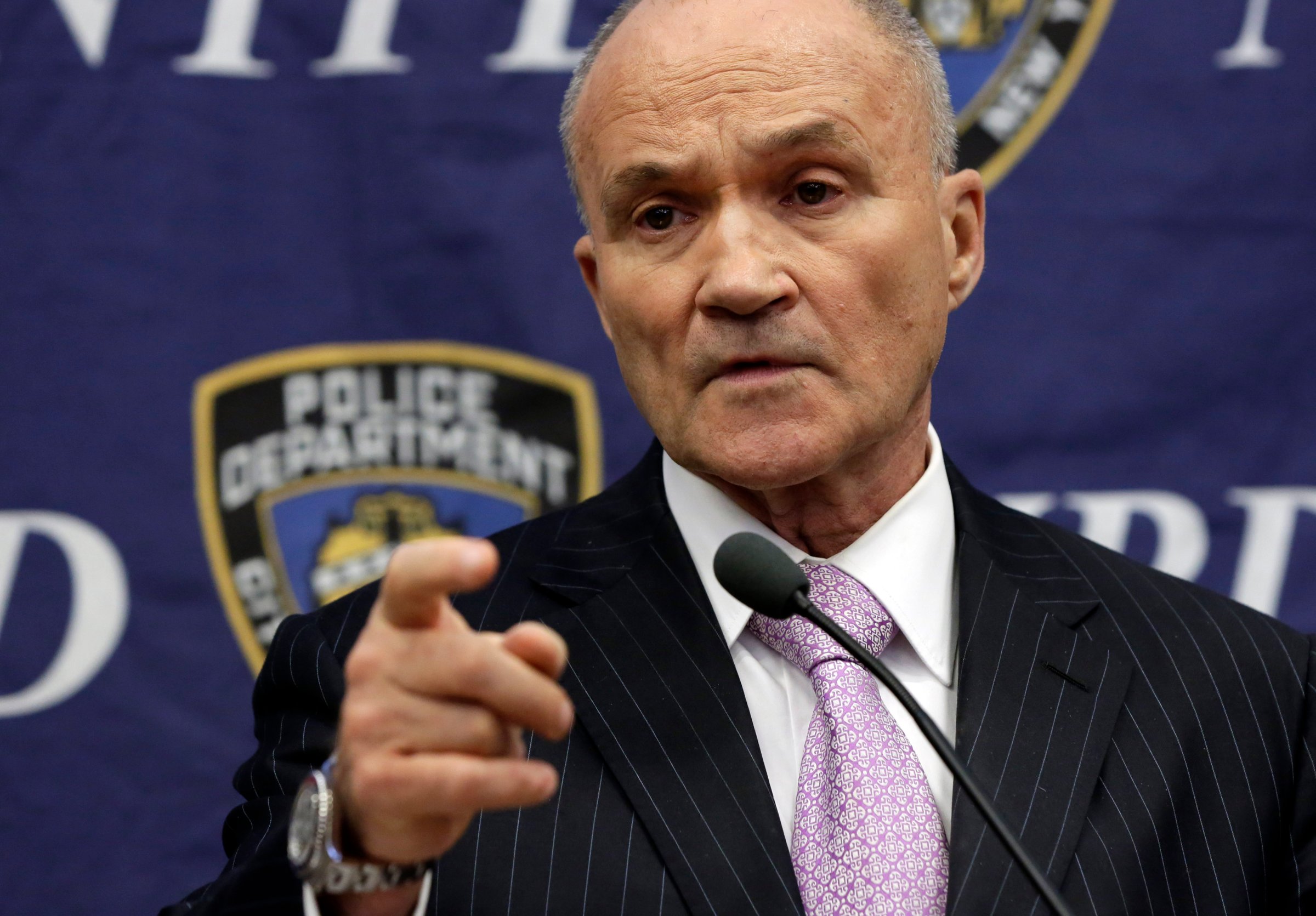

When Ray Kelly became NYPD police commissioner in 2002, the rubble from the World Trade Center still smoldered in Lower Manhattan and the city experienced on average almost two murders a day. By the end of his tenure in 2013, the city had avoided another terrorist attack, and the number of murders had fallen by half.

Kelly’s record is impressive but his tactics weren’t without controversy; the practice of stop-and-frisk—a policing strategy in which officers stop and pat-down citizens acting suspiciously—was heavily criticized by civil rights groups. Stop-and-frisk became a cornerstone of NYPD policing under Kelly, but it has since fallen out of favor. Last year, the NYPD made 47,000 stops compared to almost 700,000 in 2011, and current NYPD Police Commissioner Bill Bratton and Mayor Bill de Blasio both believe the tactic unfairly targeted communities of color.

In a new book, Vigilance, Kelly strongly defends stop-and-frisk while criticizing de Blasio for using the policing strategy as a punching bag to get elected mayor. Kelly—who now works for K2 Intelligence, a corporate investigations firm—spoke to TIME about the controversial tactic, about the state of policing today, and the impact of a string of high-profile police-related deaths.

You became New York City police commissioner for a second time just four months after the Sept. 11 attacks, and in your book you mention 16 terrorist attacks that were foiled. How close was New York City to getting attacked again?

Very close. The reason that the 16 plots did not come to fruition were the result of good work on the part of the FBI, good work on the part of the NYPD, and sheer luck. If you look at the Faisal Shahzad case, he wasn’t on anybody’s radar screen. He drove right up to Midtown Manhattan with a bomb and parked on 45th Street and 7th Avenue. But [the bomb] wasn’t assembled properly. If he had done it right, it would’ve been a bomb right in Times Square that would’ve killed many, many people.

Why didn’t the NYPD or FBI know about this guy?

There’s only so many people you can know about. He was a naturalized citizen. He was born in Pakistan. And he gave no cause to be on the radar screen.

The NYPD relied heavily on stop-and-frisk while you were commissioner. Since you left, the number of stops has gone down dramatically while crime has gone up. Do you believe those two things are linked?

Crime will go up as a result of the reduction in the number of stops. We were criticized for the number of stops. But the stops amounted to less than one stop a week per officer on patrol and less than one pat-down every two weeks by officers on patrol. The stop rate was less than it was in Baltimore, less than it was in Philadelphia, less than it was in Los Angeles, less than it was in Chicago. You have to [adjust] for population. And the administration now is talking about 40,000 [a year] being an appropriate number. You have a population in New York City that rises to maybe 10 million on a workday. Those numbers are just unrealistic.

But at the same time, in 2011 while you were commissioner, the number of stops of young black men exceeded the number of all young black men in the city.

The most reasonable metric for determining racial profiling would be the description given by the victims of violent crime or the perpetrators of those violent crimes. The description, and it has historically been this for a while, is 69% African-American. The stops have been for a while about 53% African-American. So obviously at the very least they comport to that universe that I spoke about.

Commissioner Bratton has said that you were “tone deaf” to the fact that the black community was against stop-and-frisk. Were you?

Was I tone-deaf? No. I spent a lot of time in that community. Don’t forget I was commissioner for 12 years and a year a half before that [from 1992 to 1994]. I know what the black community wants pretty well based on my presence. And it’s interesting that when Commissioner Bratton was the chief in Los Angeles, there were 875,000 stops. So I think there’s some sort of epiphany that Commissioner Bratton has gone through. He’s changed his tune when he came here.

You write in your book that black advocates were against stop-and-frisk, but a majority of black communities supported it. Why do you think it was mostly advocates who were opposed?

I base it on my own experience. I’ve spent a lot of time in black communities, a lot of time in black churches. They’re the ones being victimized in those communities. They want their children, they want themselves to be safe. Do they want stop, question and frisk being done with courtesy, with respect? Of course. They want that practice to continue because they know that it brings an element of safety that they need in those communities.

What’s your proof that stop-and-frisk has led to less crime in New York City?

In 2013, the last year of the Bloomberg administration, there was a record low number of shootings. Record low number of murders. Record low number of shootings by police officers. A 70% approval rating of the police department and 75% approval rating for me. All of those things happened on the Bloomberg watch. I think it’s a pretty proud record to stand on.

You write that New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio didn’t recognize stop and frisk as an appropriate police tactic. Why do you think he ran so hard against it?

It was a pretty shrewd political move because what Mayor de Blasio did was parse the electorate. He went to the extremes, knowing that they vote to a much greater degree. That was a hot-button issue. There was a concurrent campaign against the whole practice along with his campaign. And of course, the trial [of NYPD officer Daniel Pantaleo, who was involved in the death of Staten Island resident Eric Garner] miraculously coincided with his campaign as well.

Have the levels of trust between citizens and police hit rock bottom?

No. Relationships between the police and communities of color are much stronger than they were when I became a police officer. No question about it that the horrific events of North Charleston, S.C., some of the other incidents we’ve seen, have been a setback, but I think overall that the relationship still is much stronger than when I became a police officer, much stronger than it was 30 years ago.

People have talked about cops being less engaged and more hesitant to use force—the so-called ‘Ferguson effect.’ Do you believe that’s happening?

I do. You do see a nationwide phenomena. Police have been given signals, directly or indirectly, to engage less. And I think the consequence of that is increased violence.

If you were commissioner and you saw crime was going up in New York, what would you do about it?

I’d want to get accurate statistics and find out where the crime is happening and who’s doing the crime and do an analysis based on that.

Would you increase stop-and-frisk?

Would I encourage proactive policing? Yes.

What’s the biggest threat facing New York today?

I don’t think the threat has diminished, and it hasn’t changed much since Sept. 11. We should be concerned about individuals who are in our country being radicalized to kill their fellow countrymen for ideological reasons. I would not write off an attack by a number of people who somehow banded together. But I think the more likely scenario is one person, two people doing an attack. We are an open society, and with that comes a lot of risk. I think the major threat, the most likely, is a lone wolf or a wolfpack. They’re still very much out there.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com