Of all the investment fads and manias over the past few decades, none have been as big of a fizzle as the craze for nanotech stocks. Ten years ago, venture capitalists were scrambling for investments, startups with “nano” in their names flourished and even a few nanotech funds launched hoping to track a rising industry.

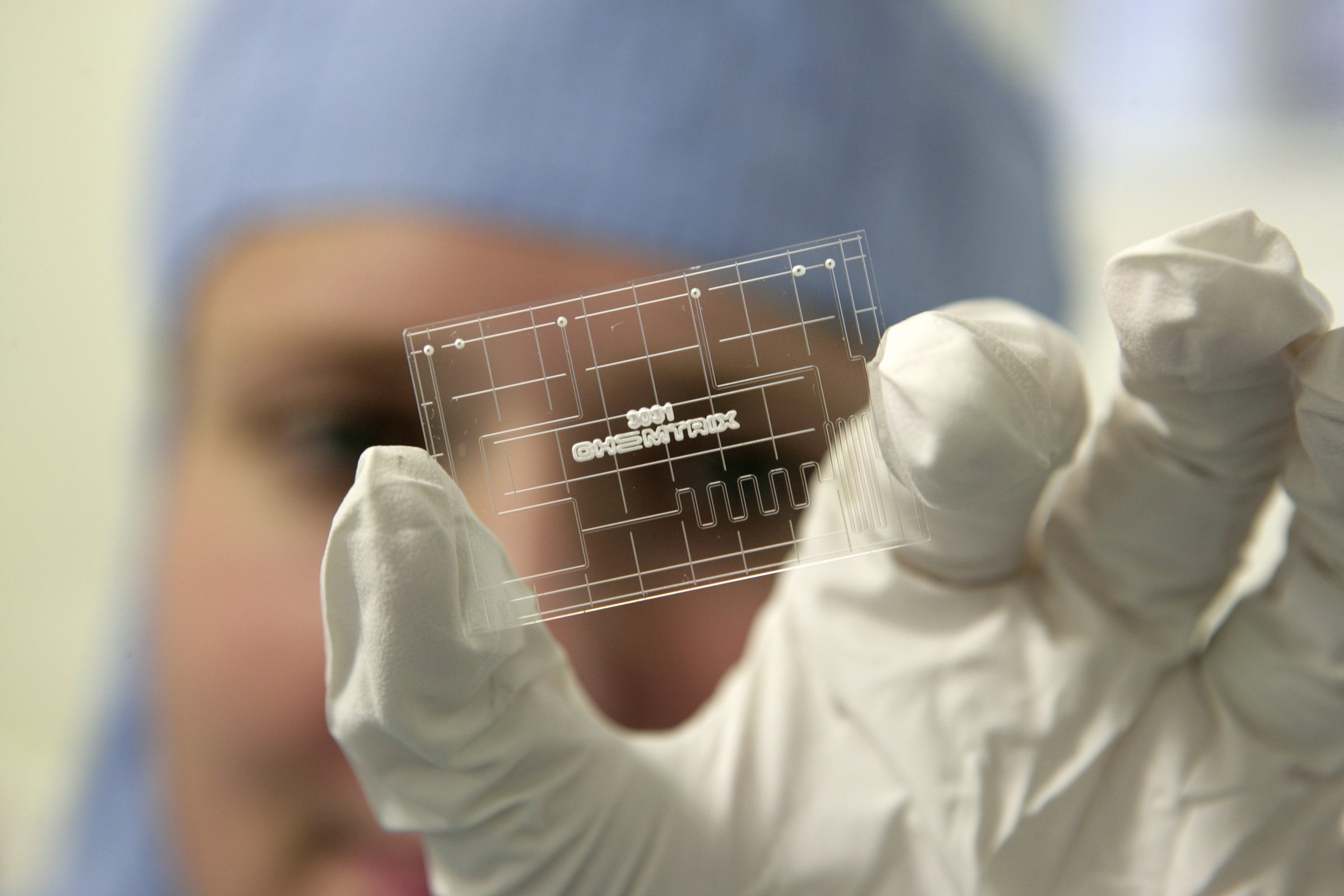

And today? Nobody in the stock market gets excited about the phrase “nanotech” anymore. Which is strange, because nanotechnology itself – that is, the science and engineering conducted on a molecular scale, measuring less than 100 nanometers – is yielding applications and products in a number of industries, just as its more sensible supporters have long predicted.

Back in 2005, the year when nanotech mania peaked, a gold rush mentality took hold. There were 1,200 nanotech startups worldwide, half of them in the U.S. VCs invested more than $1 billion in nanotech in the first half of the decade. Draper Fisher Jurvetson had nearly a fifth of its portfolio in the nanotech sector, and Steve Jurvetson proclaimed it “the next great technology wave.”

With investors still feeling the hangover of the 2000 dot-com bust and a subsequent collapse of biotech stocks two years later, there was a strong appetite for a new wave of technology. In 2000, President Bill Clinton doubled U.S. investment in nanotechnology, and President George W. Bush authorized billions more in 2003.

Speculators began flocking to materials, chemical and pharmaceutical companies that claimed to be doing work on the nanoscale, prompting other companies to rewrite their business descriptions to embrace nanotechnologies. Nanotech became, briefly, a magical buzzword.

Companies that invested in nanotech, like Harris & Harris and Arrowhead Research, were publicly traded, offering stock investors access to a portfolio of nanotech plays. Stock indexes like the Lux Nanotech emerged, as did ETFs based on them, allowing another ground-floor entryway for small investors who wanted in on the next big thing.

Top 10 Tech Product Designs of 2014

Ten years on, precious few of the nanotech stocks and venture-backed startups have delivered on their investment promise. Harris & Harris and Arrowhead are both trading at less than a tenth of their respective peaks of the last decade. Invesco liquidated its PowerShares Lux Nanotech ETF in 2014, after it underperformed the S&P 500 for seven of the previous eight years.

And many of the surviving companies that touted their nanotech credentials or put “nano” in their names now describe themselves as materials companies, or semiconductor companies, or – like Arrowhead – biopharma companies, if they haven’t changed their names entirely.

That kind of corporate rebranding shows more than how severe the investor backlash to the nanotech hype was. It also illustrates what really happened to nanotechnology over the past ten years. Nanotechnology, as some voices tried to explain years ago, wasn’t an industry. It was a broad field where engineering and science on a molecular level was begging to take root. It never became an industry itself because the technology behind it enhanced and improved many different industries.

According to Google Trends, searches on “nanotechnology” have steadily trended downward to between 15% and 20% of the levels of a decade ago. Searches for “nanotech” – the catchy buzzword preferred by investors – have grown even quieter. And yet each year there are more interesting applications that wouldn’t be possible without nanotechnology.

One better-known example is semiconductors, which began employing a 65-nanometer manufacturing process in 2007. Intel this year announced a processor with transistors measuring 14 nanometers, small enough to fit 1.3 billion transistors on a chip, and is pushing for a 10-nanometer process.

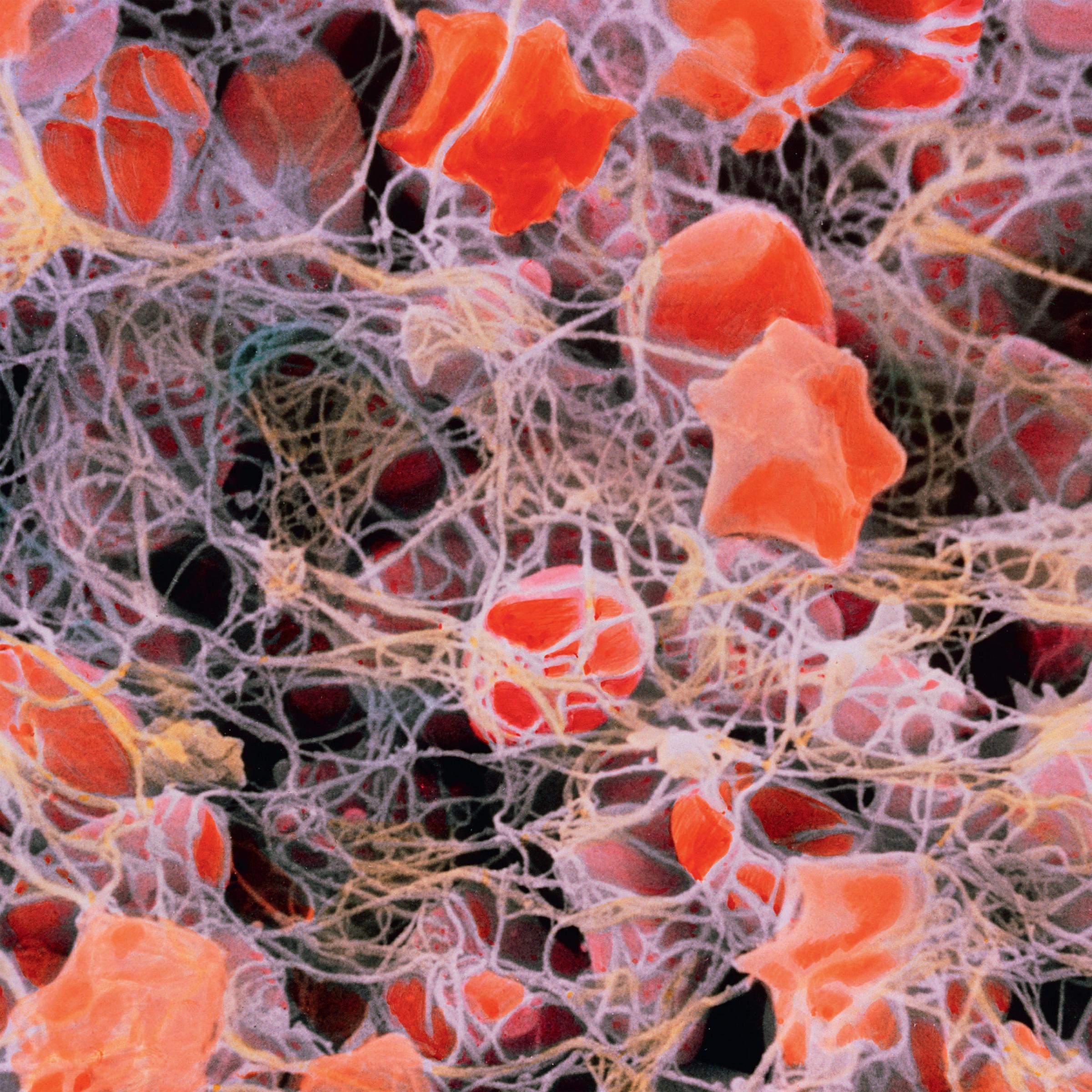

Meanwhile, research for new drug therapies are increasingly relying on molecular-level science, while gold nanoparticles are being developed as way to diagnose and treat cancers. Touchscreens, LEDs, displays, batteries, water desalination, energy efficiency – all are areas that are benefiting from nanoscience, with products already in the market or approaching there. IBM, for example, is looking into carbon nanotubes as a promising alternative to silicon, which isn’t useful in transistors below 10 nanometers.

Nanotechnology never had its Facebook, its multibillion dollar blockbuster IPO that made clear how a new technology is changing the world. Instead, it’s enabling a lot of mostly incremental change in older industries. It may not be as visible as a social network, but it’s even more widespread. Most of the investments, however, have been coming not from VCs but from governments or deep-pocketed, diversified giants like IBM or GE.

And while Facebook, like the most celebrated of Silicon Valley’s startups, went from idea to ubiquitous product in less than a decade, most nanotechnology applications taking much longer to find a market. That’s much longer than the five-to-seven year lifespan of many venture funds, let alone the quarter-to-quarter mentality of many publicly traded companies.

But given that the field is only a couple of decades old, it’s not bad. And it’s in line with what nanotechnology’s more sober advocates have been predicting all along. Even if a lot of antsy, speculative investors wished it had been otherwise.

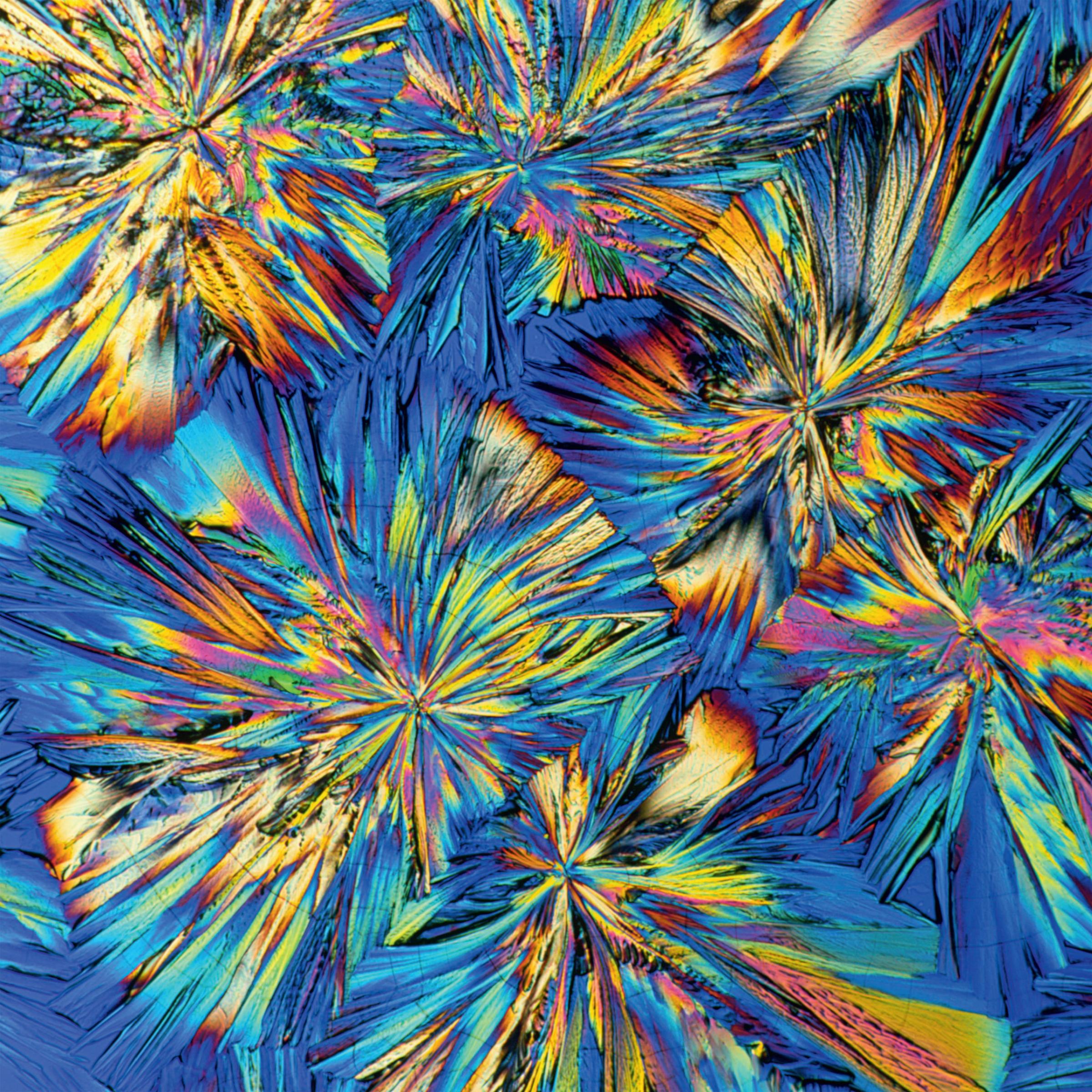

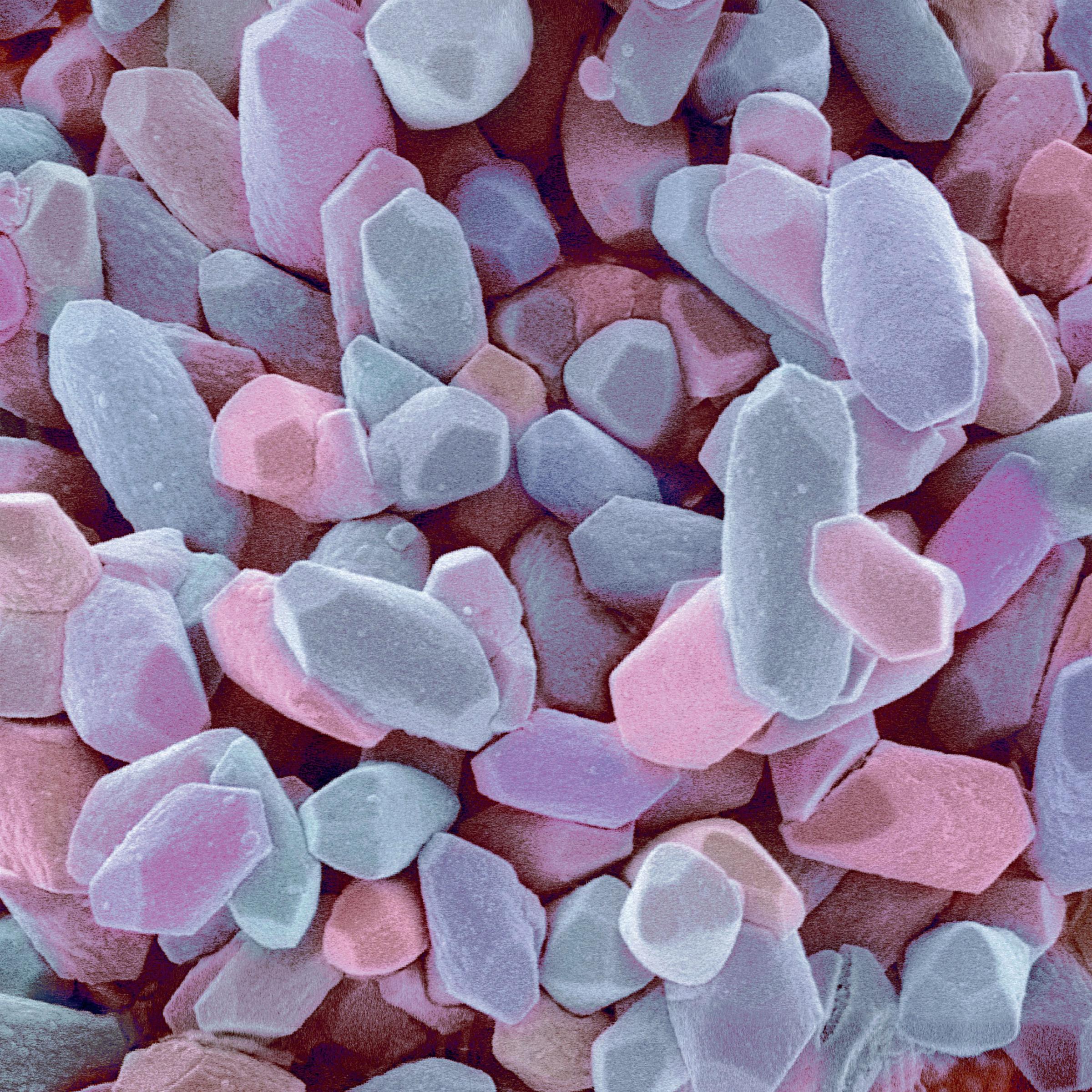

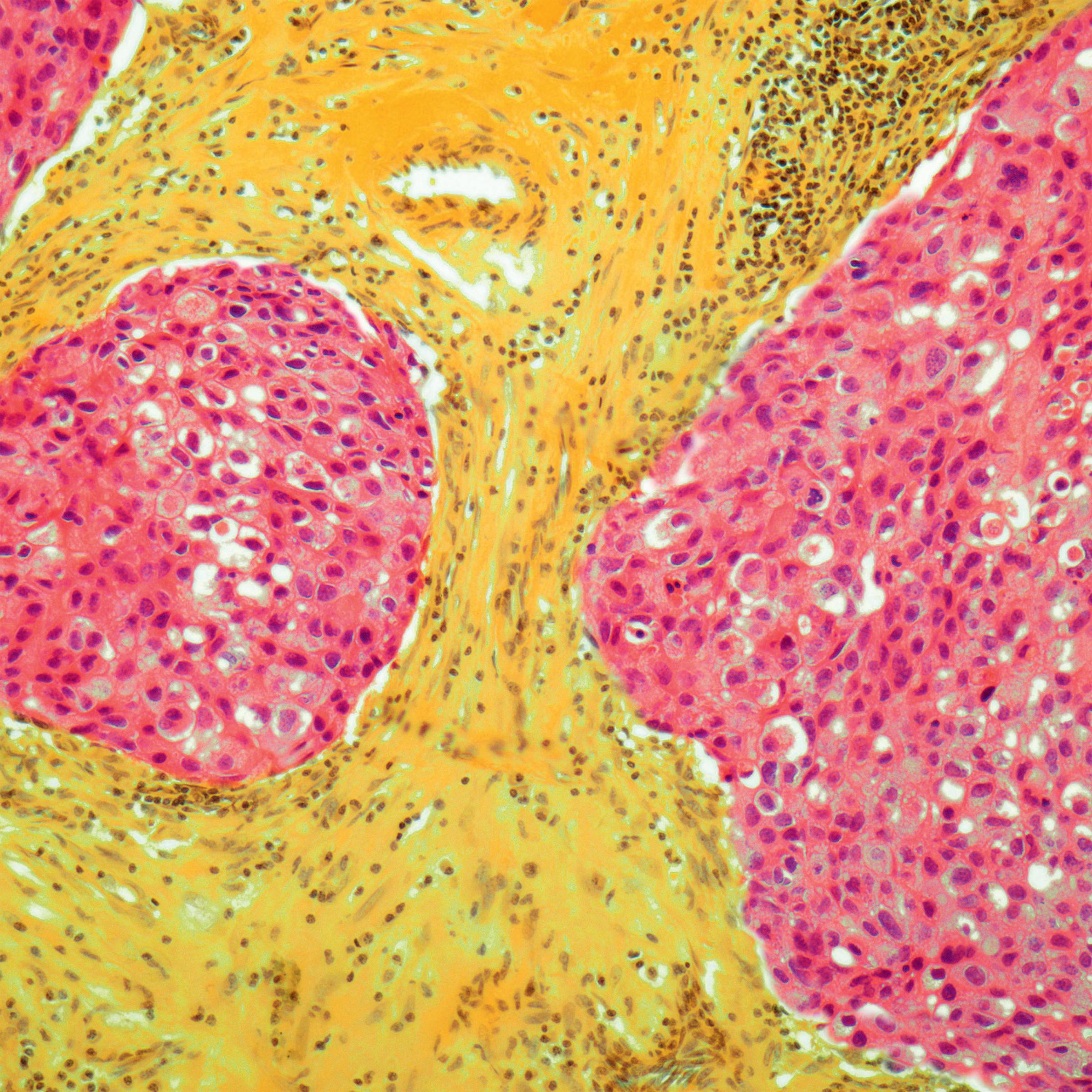

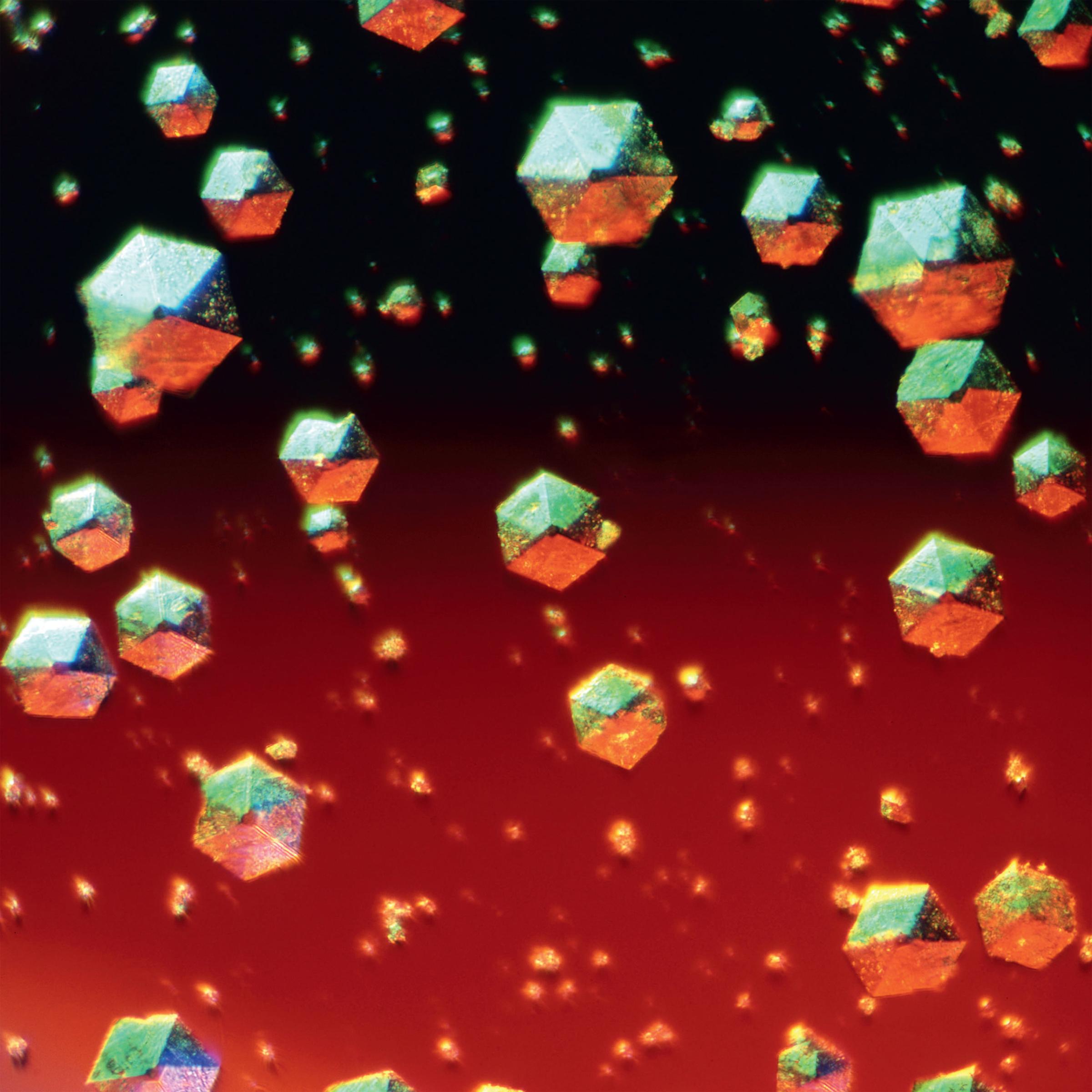

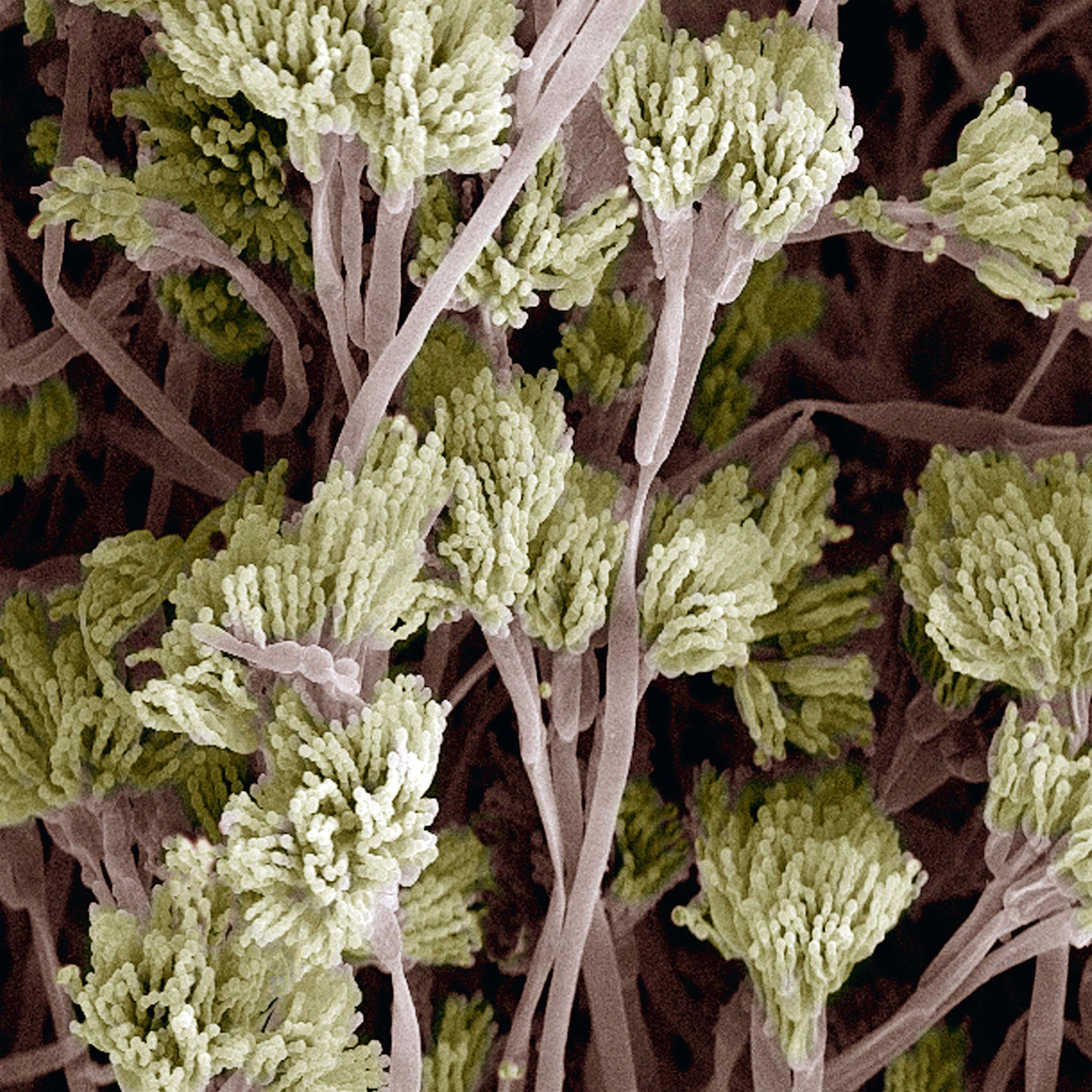

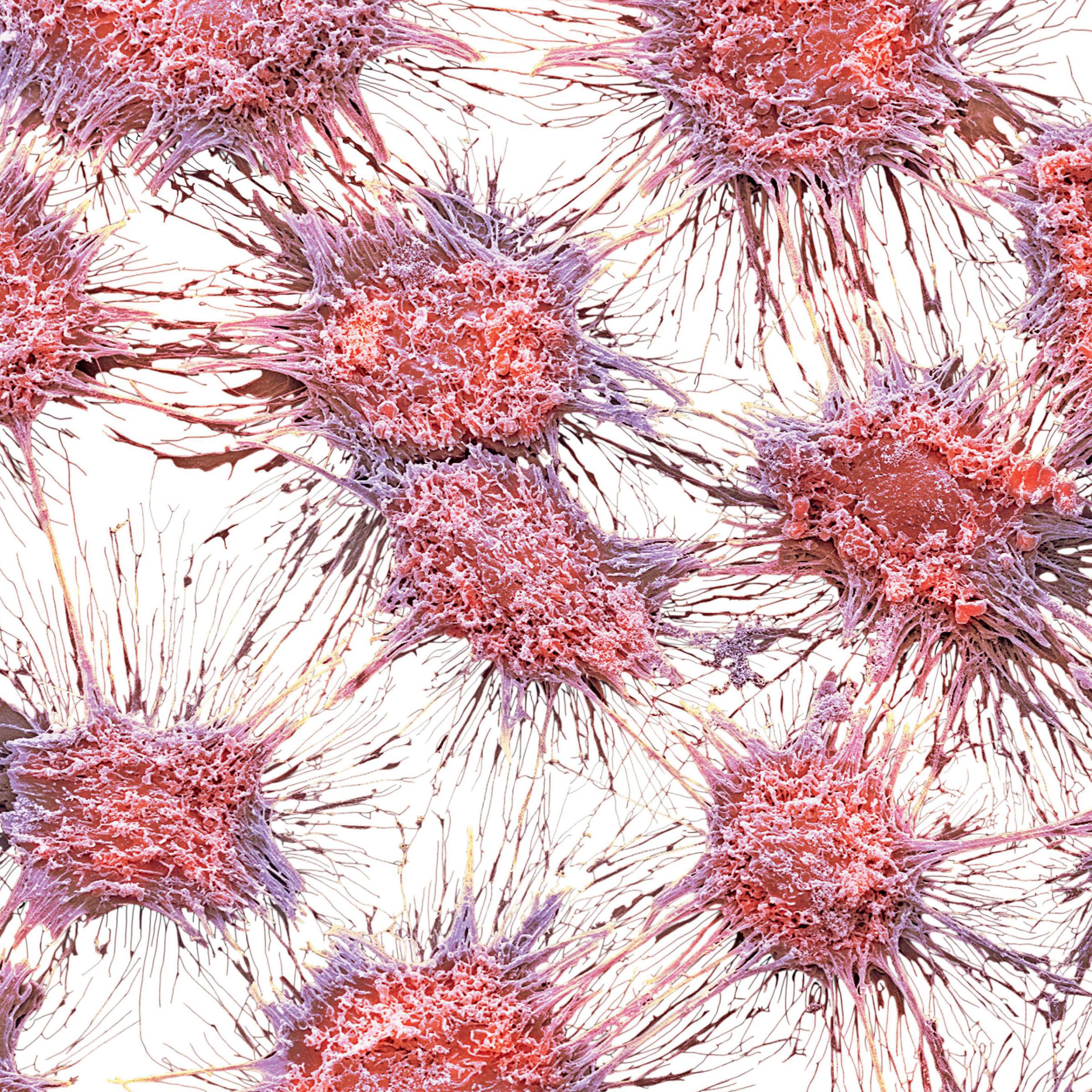

See the Human Body Under a Microscope

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Biden Dropped Out

- Ukraine’s Plan to Survive Trump

- The Rise of a New Kind of Parenting Guru

- The Chaos and Commotion of the RNC in Photos

- Why We All Have a Stake in Twisters’ Success

- 8 Eating Habits That Actually Improve Your Sleep

- Welcome to the Noah Lyles Olympics

- Get Our Paris Olympics Newsletter in Your Inbox

Contact us at letters@time.com