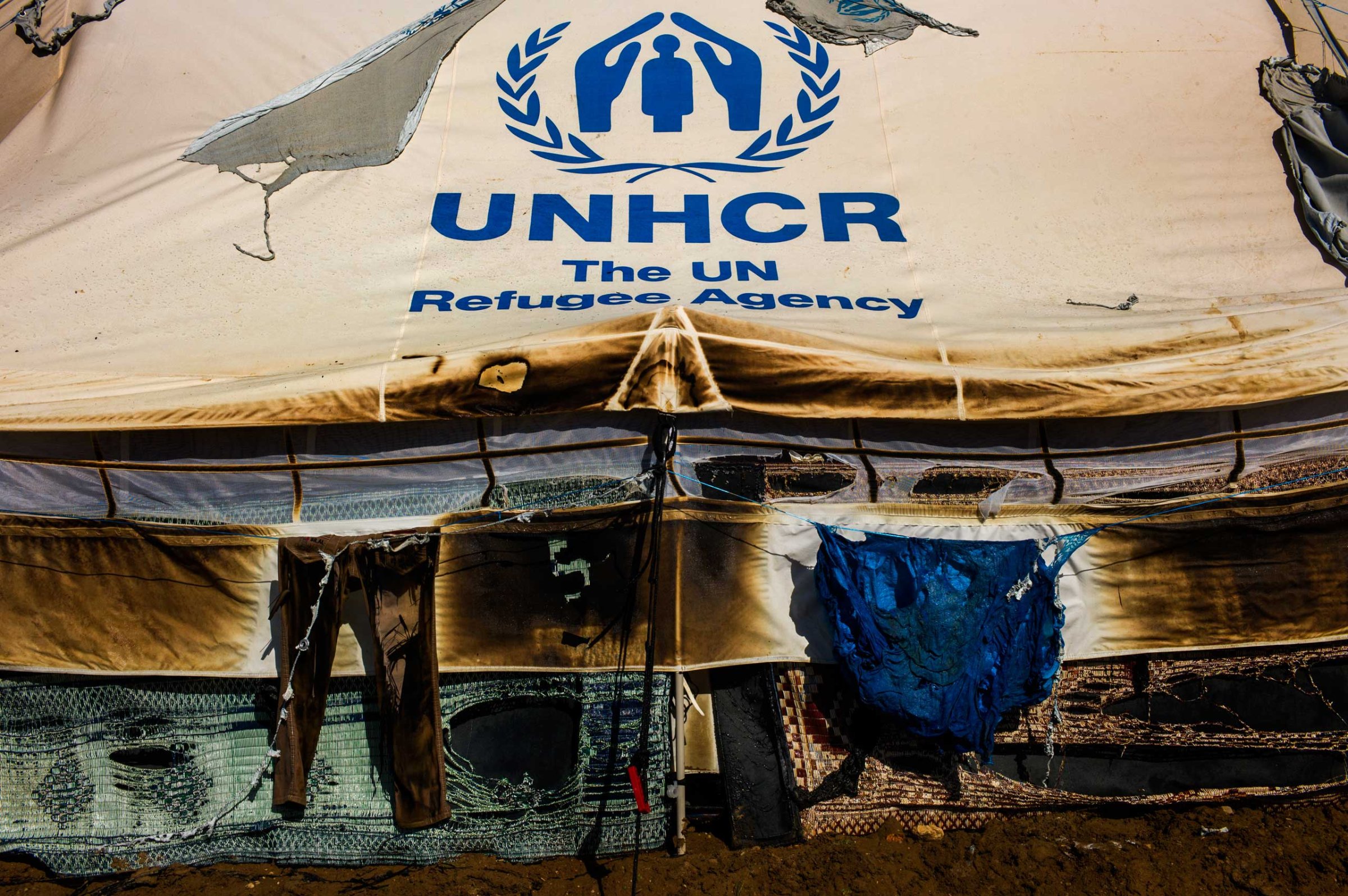

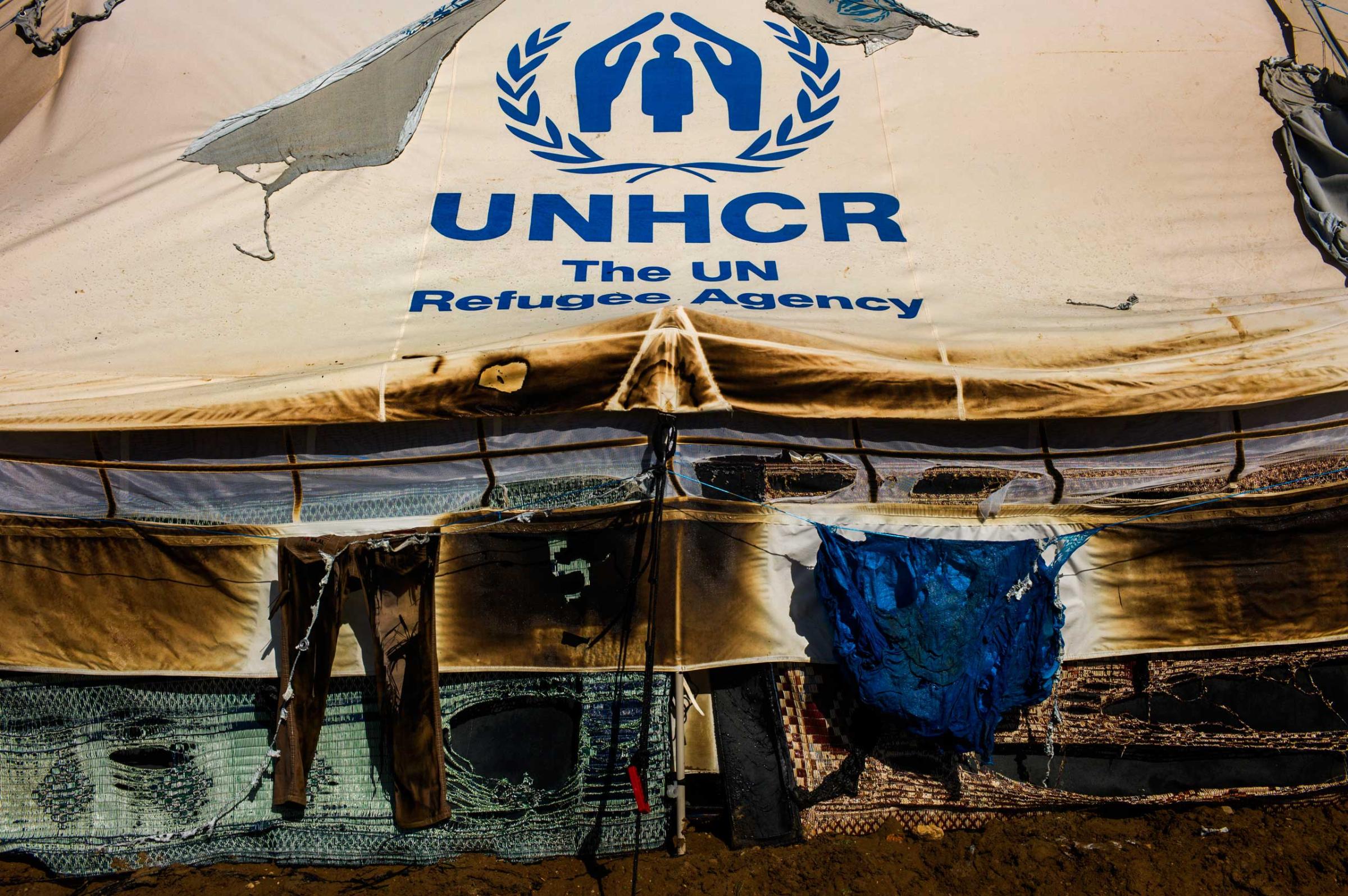

“There are very few three-month-long assignments out there,” says freelance photographer Ivor Prickett. So when the Irish photographer was offered one by the United Nations Refugee Agency, he didn’t hesitate. “I was approached [to cover] the Syrian refugee crisis in the Middle East. It was a topic I was already interested in, so it was not a hard decision to say yes.”

As the competition for editorial assignments has intensified over the last decade, Prickett and many of his colleagues have turned to non-governmental organizations to sustain their work. The UNHCR has been a particularly fruitful employer, commissioning dozens of professional photographers around the world.

Now, as Europe is dealing with its largest refugee crisis since World War II, the organization has dispatched numerous photographers to the region. It started with the rise of the Islamic State, whose strategic and geographic gains forced hundreds of thousands of people to flee their homes. The UNHCR sent freelance photographer Dominic Nahr to Iraq to cover that aspect of the story. Fabio Bucciarelli was dispatched to Sicily last May to record the arrivals of thousands of refugees in Italy. And Prickett was asked to follow Syrian and Iraqi people who had sought refuge in Turkey and Greece. They are just three of the many photographers whose work with the organization is important to its mission, says Susan Hopper, UNHCR’s photo editor. “We look for photographers who capture people’s humanity and who understand what viewers will connect to,” she tells TIME. “That connection is extremely important, especially with the situation in Europe.”

The news that thousands of refugees and economic migrants are arriving on the continent can be unsettling for a European public that is still dealing with the after-effects of a devastating economic crisis. “There’s a lot of talk and fear about refugees and so it’s critical that people can see for themselves what’s happening,” says Hopper. “We choose photographers who can show that this refugee is a regular person who has run out of options and is being forced to do something desperate to protect his or her family. And when you see photos of these people’s faces when they arrive on the beach in Greece, it clicks. Seeing how traumatized and scared these people are generates empathy and understanding and changes attitudes and behaviors. That’s the connection we want to make.”

A typical UNHCR assignment starts with a meeting with the organization’s photo editors in Geneva. “We talk through what our aims and needs are,” says Prickett. “I will make a rough plan of where I want to go and then contact the locally-based UNHCR staff to get an idea of what’s going on and where I need to be.” For the Irish photographer, that process is very similar to the one he applies to his personal work or to magazine assignments. For example, when in Greece, Prickett was able to work independently. “I was simply photographing what I was seeing on the ground, documenting the movement of people and gathering testimonies from refugees,” he says.

Another aspect aspect the UNHCR stresses is the need for extended and accurate captions, which include quotes, subjects’ names and contextual information, to populate the organization’s photo database. That database is called Refugees Media and it’s an essential part of the organization’s activities. “After a day of shooting most photographers stay up half the night writing captions and filing into our media database,” says the U.N.’s Hopper. “It’s not uncommon for the High Commissioner’s spokesperson to tweet a photo 15 minutes after it’s been filed by a photographer in the field. Having that immediacy — in the form of a refugee’s face and name and words — is what helps us to break through the noise and get people to care.”

The agency also tasks photographers with shooting longer, in-depth stories each month, which are then combined with articles, charts and videos and published on the multimedia platform Tracks. “Great photography plays a central role on Tracks,” says Christopher Reardon, the chief of content production at the agency. “[The U.N. project is] racking up more page views and longer dwell times than our conventional pages.”

For the photographers, a UNHCR assignment can offer access to that expanded audience, but it also comes with questions about independence and objectivity. They have to produce strong single images that can define an entire story, and have to keep an eye out for “emotional stories with a positive outcome, especially stories about women and children,” says Bucciarelli. “And since the agency deals with refugees and not with economic migrants, the focus was on people who had fled from internationally-recognized wars.”

But as Nahr points out, that’s no different from working with any client. “I understand that every organization, whether they are a magazine, a newspaper, a charity, has an agenda,” he says. But, Nahr adds, his time with the UNHCR rekindled his relationship with photography after a difficult few years. “It has re-sparked my love for taking photographs and reporting,” he says. “I could let go of the usual stress, anxieties and restrictions of not having long assignments and constantly hustling to look for money to pay for drivers, fuel, translators, housing, et cetera. I felt I could use all of my energy to focus on being truly with the people I am documenting over and over again.”

Olivier Laurent is the editor of TIME LightBox. Follow him on Twitter and Instagram @olivierclaurent

![Iraq / Syrian Refugees / Nishan (centre) stays standing while he eats his lunch so that his sister in law and her children have a seat at the table in Amed Restaurant in Roviya during a lunch break "Of course the future of my family will be better if they stay in Kurdistan. For me, it would have been better to stay in my home [in Kobani], but we were forced to leave. We have no other option, just to leave our country and go somewhere else." He and his family is traveling with over 300 other Syrian refugees from Kobani from Ibrahim Khalil Border crossing to Gawilan Refugee camp in Iraq's Kurdish Region. / D. NAHR / March 2015](https://api.time.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/refugee-crisis-unhcr-dominic-nahr-003.jpg?quality=75&w=2400)

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com