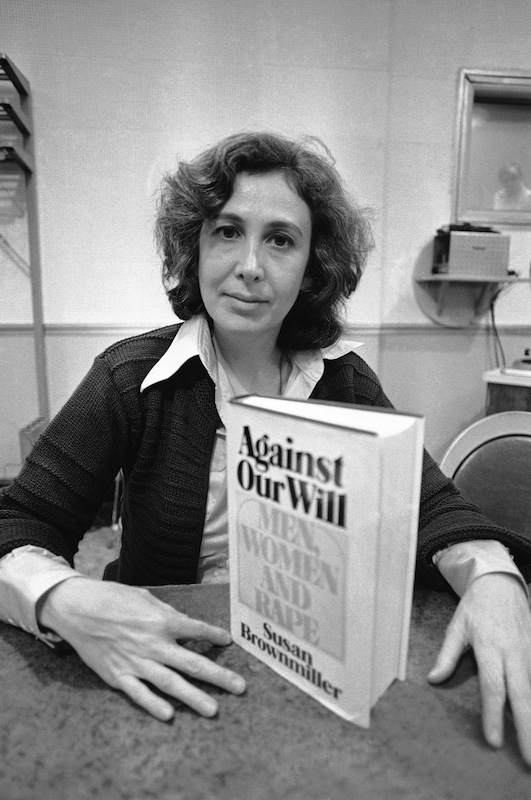

In October of 1975, TIME named feminist journalist Susan Brownmiller “the first rape celebrity who is neither rapist nor rapee.”

The very idea of a “rape celebrity” sounds shocking today, and it was at the time as well. Brownmiller’s celebrity status was the result of her groundbreaking book Against Our Will: Men, Women, and Rape, published precisely forty years ago. The bestseller was one of the first books to define rape as a political problem rather than an individual crime of passion. In addition to launching Brownmiller into the public eye—she appeared as one of TIME’s 12 “Women of the Year” two months later—Against Our Will brought the ideas of the feminist anti-rape movement into the mainstream.

Decades later, her arguments are still relevant as politicians, college administrators and activists struggle to address the problem of sexual violence.

Rape had been cloaked in stigma and silence for much of American history. Prior to the women’s movement of the 1970s, it was understood to be a rare occurrence, as few survivors came forward. The reasons for this are now obvious: In the 1960s and earlier, a rape victim seeking help would be met, instead, with blame and suspicion. Neither police departments nor hospitals had trained trauma counselors or procedures for collecting evidence or testing for disease. Filing criminal charges required “corroboration” of the assault from witnesses, and a woman’s sexual past could be used by the defense to discredit her accusation. Brownmiller’s book was part of a larger effort by feminists to change both laws and public attitudes, and to transform a culture that undervalued women’s bodily autonomy. Against Our Will came out just as anti-rape activists began to create crisis centers, hotlines, self-defense classes and other forms of support for rape survivors.

In her book, Brownmiller identified a number of deeply ingrained myths about rape: that it is motivated by uncontrollable male lust rather than violence, that female sexuality is inherently masochistic and inviting of rape, and that women “cry rape with ease and glee.” Against Our Will offered a coherent counter-discourse about rape, reframing it as an act of power, even mass terrorism, which had the consequence of controlling female behavior. In other words, Brownmiller argued, rape was fundamental to the patriarchal domination of women.

TIME described this thesis as “startling,” and called Against Our Will a “convincing and awesome portrait of men’s cruelty to women.” Indeed, Brownmiller’s stated purpose in the book was to “give rape its history,” and she details incidents of sexual violence dating back to the ancient Babylonians, as well as traditions of wartime rape in the modern era. Her emphasis on rape as a tactic in war and other forms of political conflict framed sexual violence as a collective social problem as well as a deliberate, calculated act meant to humiliate and degrade the victim.

Part of what made Against Our Will so radical was its attention to date rape and spousal rape. “The typical American rapist might be the boy next door,” Brownmiller wrote. She cautioned that men in intimate relationships with women “are invested with an assumed benevolence that may not exist.” Looking at rape perpetrated by boyfriends and husbands challenged the popular narrative of the rapist as a depraved stranger jumping out of the bushes. It also defied the widespread perception that a woman “belonged” to her husband and existed in a perpetual state of consent. Brownmiller’s insights here, along with the work of other feminist activists, helped bring about the first marital rape laws in the United States, passed in the late 1970s.

Against Our Will had its fair share of critics; most notably, Angela Davis, bell hooks and other feminists of color, who took issue with Brownmiller’s treatment of race as it related to sexual violence. “Many of [the] arguments are pervaded with racist ideas,” Davis later wrote, including “the resuscitation of the old racist myth of the Black rapist.” She referred particularly to Brownmiller’s discussion of Emmett Till, a 14 year-old black boy lynched in 1955 for whistling at a white woman. Brownmiller called the whistle a “deliberate insult just short of physical assault.” Davis points out that in Against Our Will, Till—whose killing would prove to be a galvanizing incident for the civil-rights movement—emerges “as a guilty sexist, almost as guilty as his white racist murderers.”

Asked recently if her positions on the topic have evolved, Brownmiller told TIME that she “stands by every word” of her book. Nor does the author budge on her anti-prostitution and anti-pornography stance, which Against Our Will argued was “central to the fight against rape,” even as many feminists now reject the idea that decriminalized sex work and pornography contribute to violence against women. Brownmiller remains steadfast in her commitment to a 1970s radical feminist worldview, although a new generation of activists challenges that ideology. The anti-rape movement has in fact changed in many ways since 1975, expanding its focus to include the experiences of male survivors, the problems with college sexual conduct policies and the issue of other forms of unwanted sexual attention, such as street harassment.

Still, Against Our Will laid the groundwork for that activism. What today’s feminists describe as “rape culture” has its roots in Brownmiller’s theory of rape as a means of social control, her emphasis on gender role socialization and her critique of the glorification of sexual violence in the media. When young women share their experiences with rape through art projects, at university events, and on social media, they are participating in a tradition of “speaking out” initiated by second-wave feminists like Brownmiller. Survivors of sexual violence now live in a world where they know they are not alone, where they can access a variety of resources and where discussions about consent happen with frequency.

In fact, the rate of sexual assault and rape decreased by about 50% between 1993 and 2013, according to the Bureau of Justice Statistics—but it still happens. According to RAINN, a rape takes place every two minutes, with 68% of them going unreported, and only two out of every 100 rapists serving prison time. Brownmiller continues to see the problem as a political one. Feminists have “lost ground on rape,” she tells me, “as our nation has drifted rightward on women’s issues.” Asked what challenges remain for the anti-rape movement, Brownmiller instead looks at the big picture; to her, it is all a matter of patriarchal power. “White men still rule,” she points out. “Emphasis is on the men in that sentence.”

Historians explain how the past informs the present

Sascha Cohen is a PhD candidate in the history department at Brandeis University, specializing in the social and cultural history of 1970s America.

Read TIME’s 1976 ‘Women of the Year’ issue, here in the TIME Vault: A Dozen Who Made a Difference

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com