Standing at a refugee stop in the Austrian town of Nickelsdorf, near the Hungarian border, 17-year-old Ahmad explains that he no longer owns much of anything. After fleeing their home in Deir ez-Zor, Syria, Ahmad and his family hope to end up “in Germany, Finland, Sweden” — whichever country will take them in. As Ahmad recounts how his family had to abandon all of their belongings — carrying only small packs of clothing with them — he unwraps a chocolate wafer handed out by Austrian volunteers. And though he has next to nothing, Ahmad breaks the chocolate in two and politely offers me half.

This small, but remarkable act of sharing was something photographer James Mollison and I would come to witness over and over as we interviewed refugees on a recent trip to Austria. Though everyone we met had an urgent need — for a hot meal, for a working phone signal, for information — many were more than willing to share what little they did have, whether it was their time or their stories.

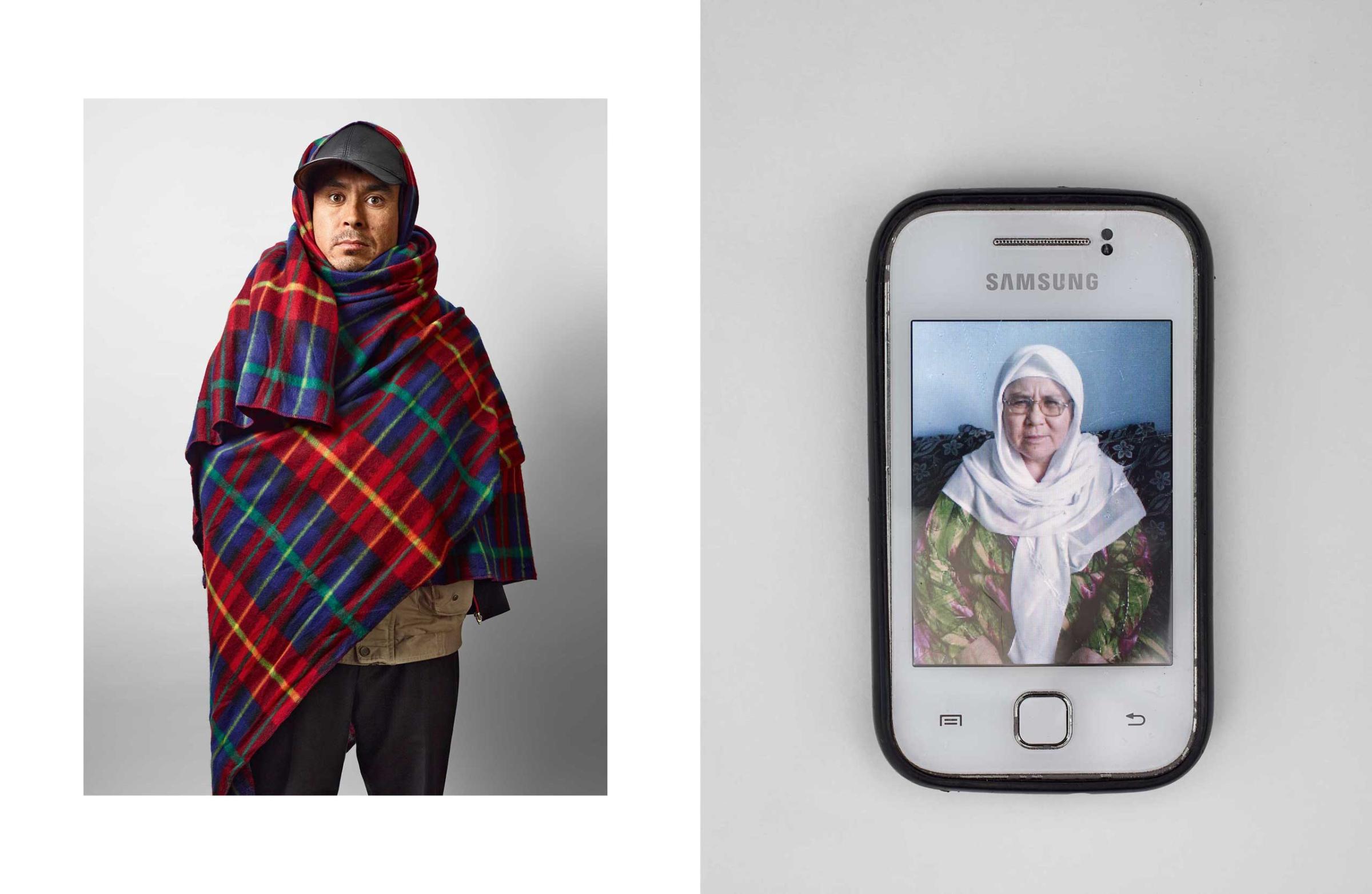

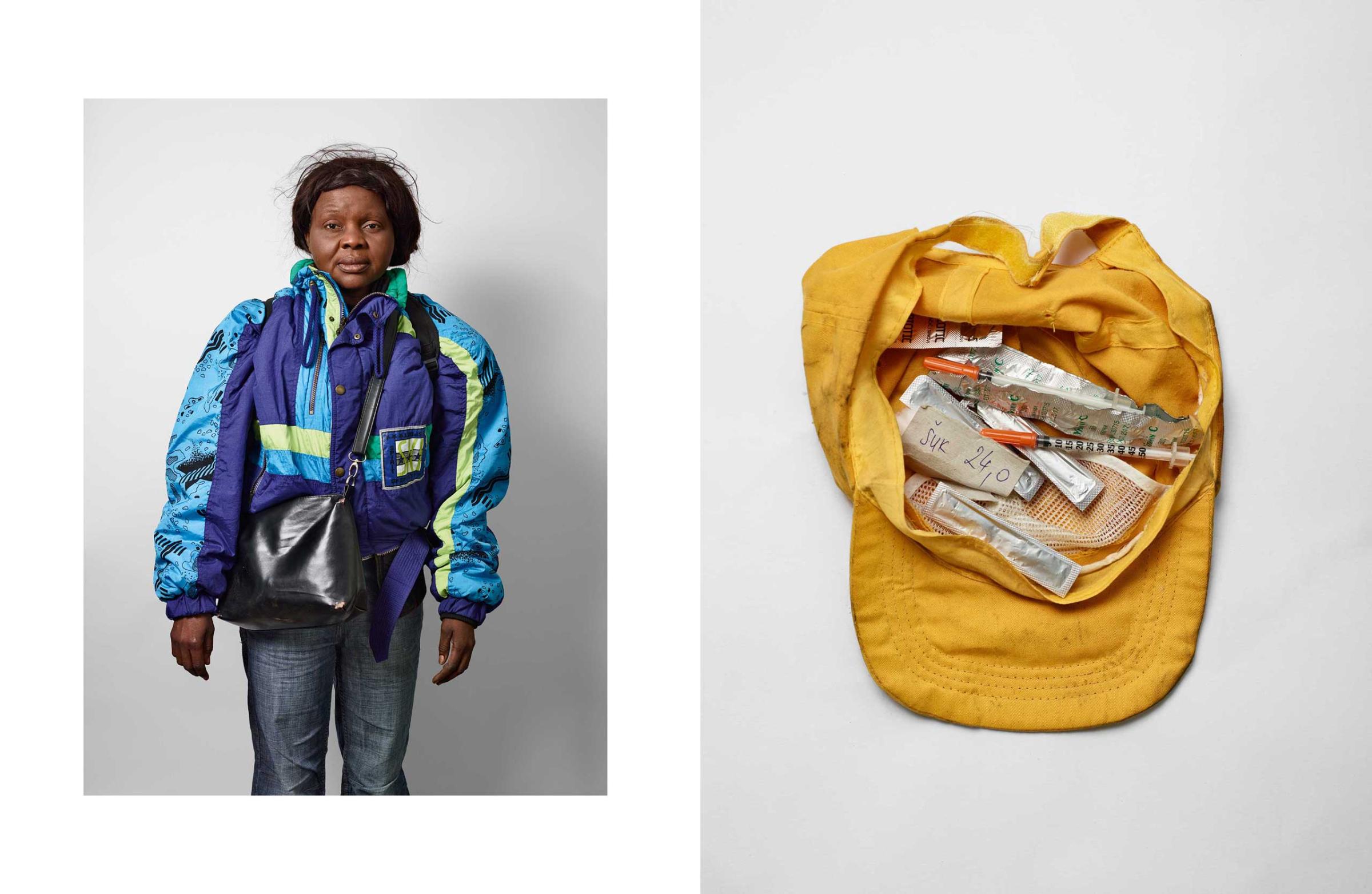

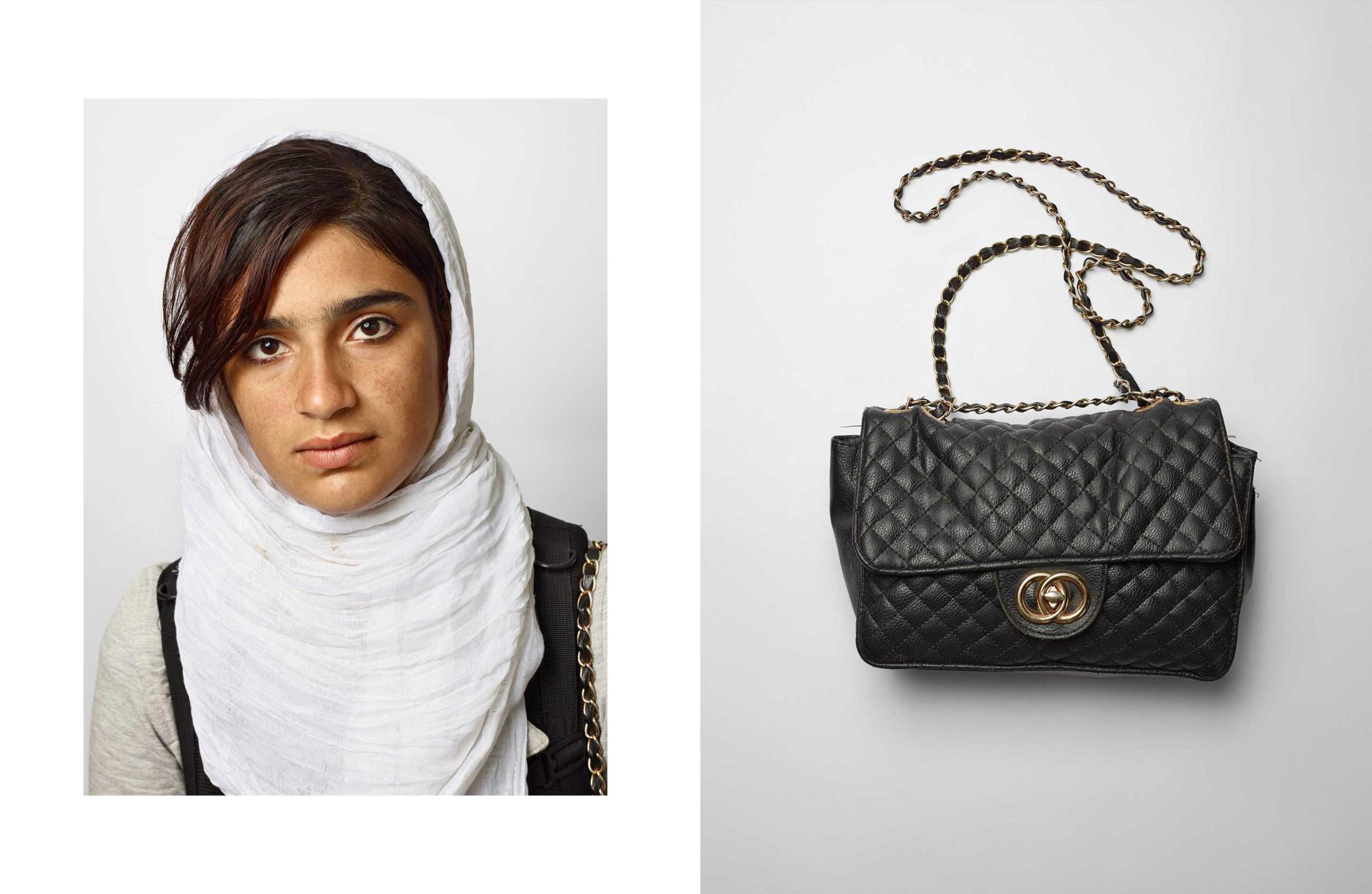

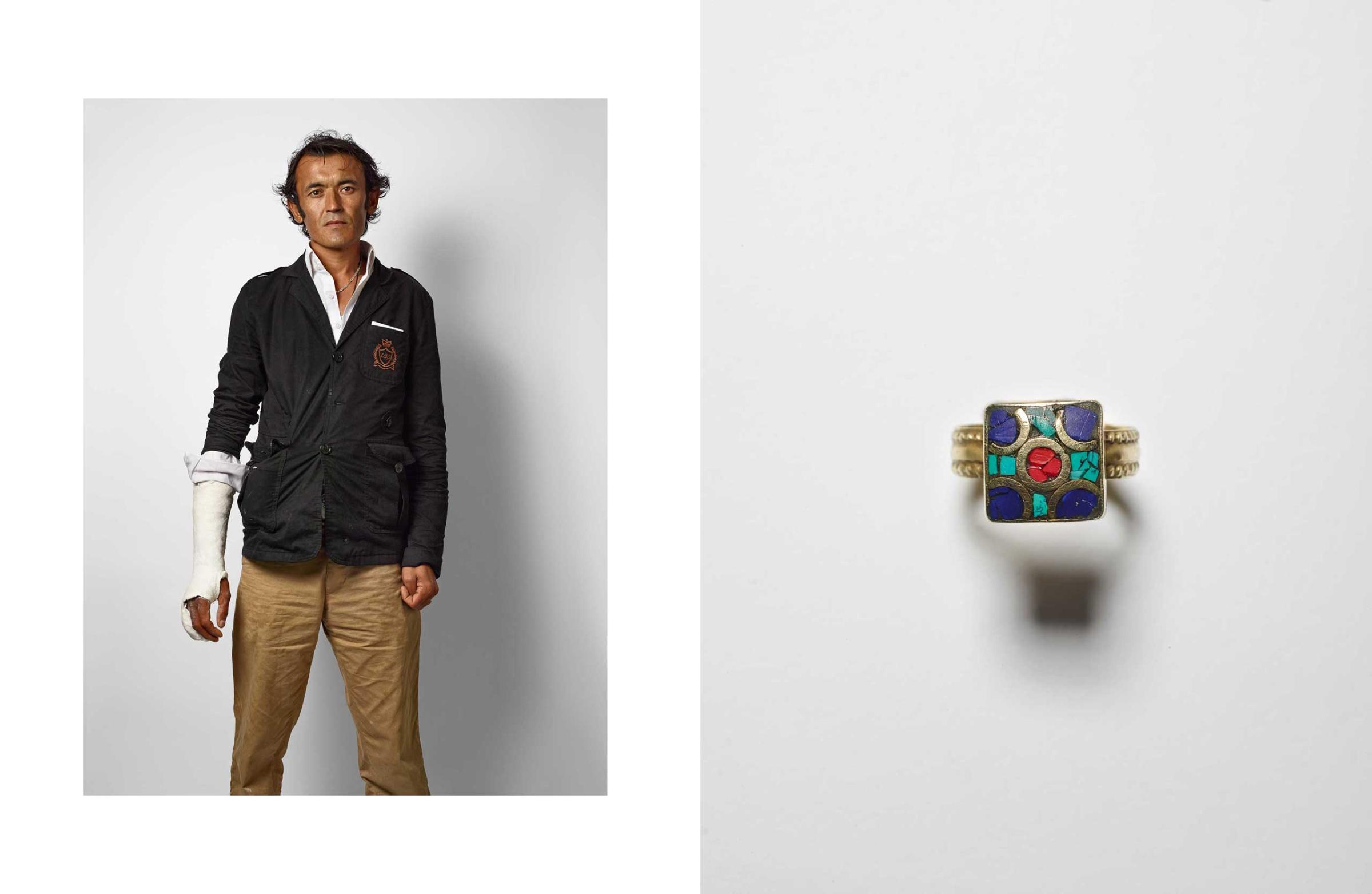

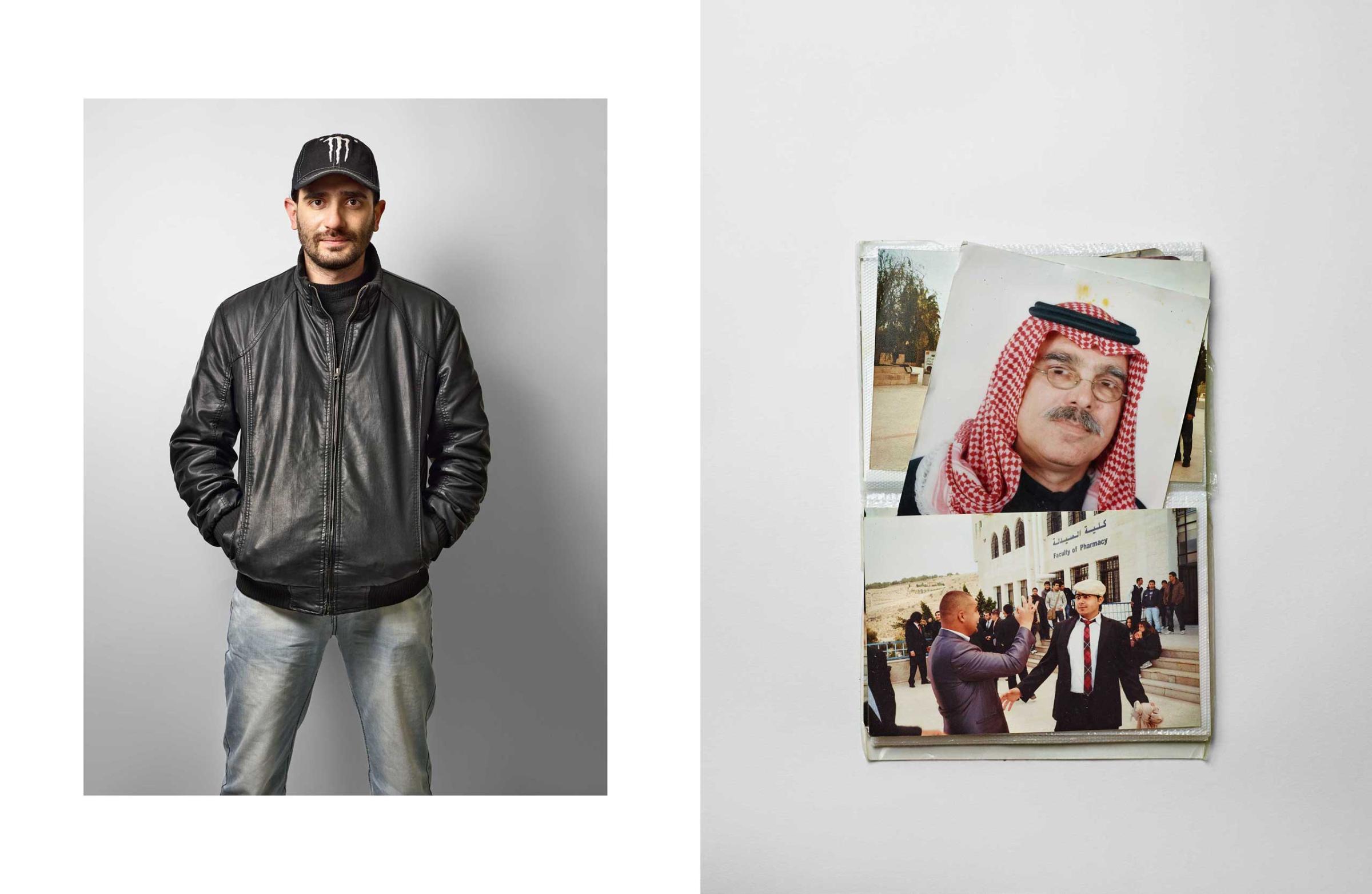

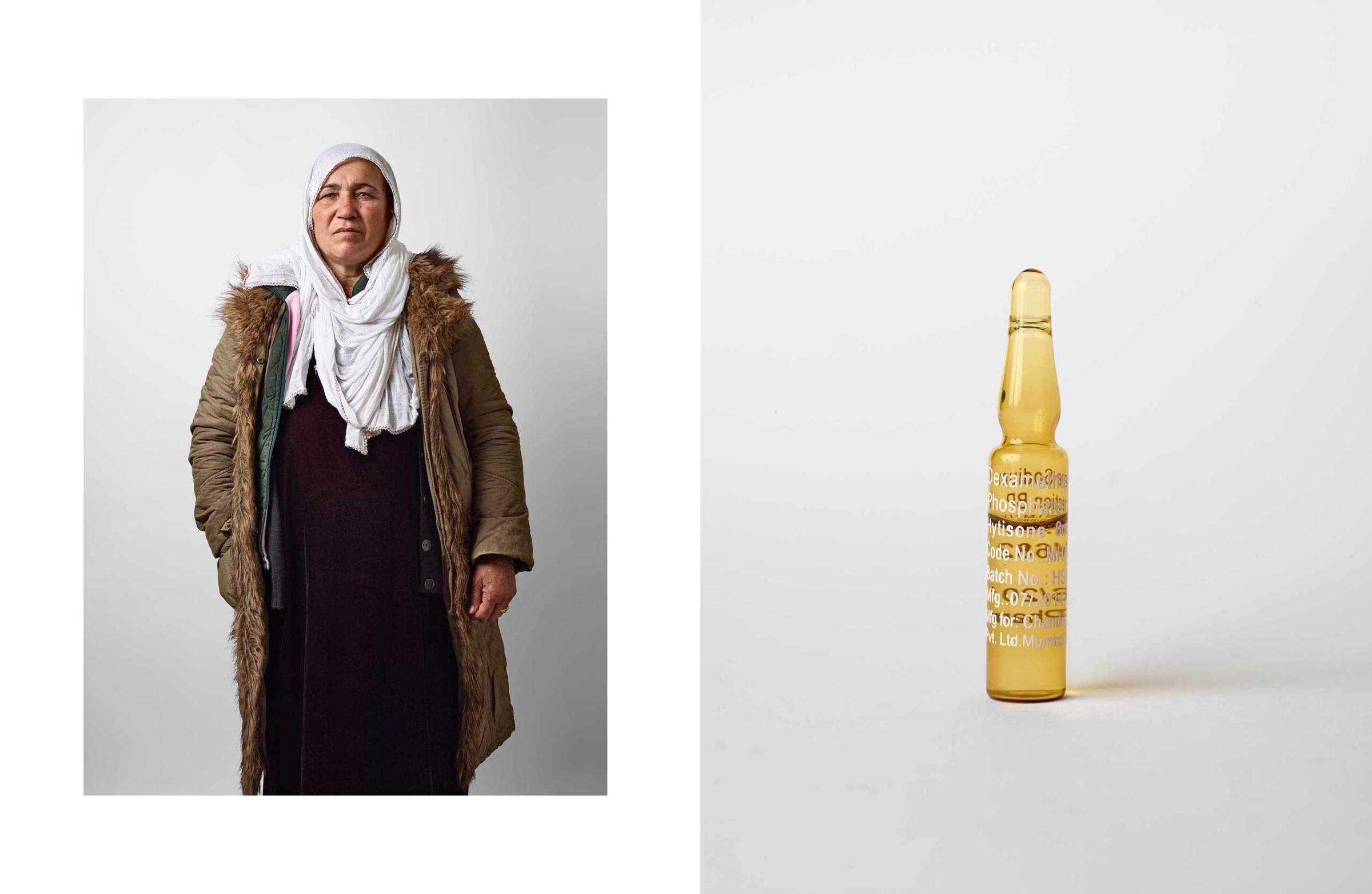

One by one, refugees agreed to stop and have their portraits taken by James, in a makeshift studio he had assembled in a tent, alongside discarded wool blankets and ruined articles of clothing. We heard story after story of smugglers shepherding desperate refugees into tiny, ramshackle dinghies and then forcing them to throw their only bags overboard, in order to prevent the boats from sinking. “We did it to save our lives,” says Marie, a 32-year-old woman who had traveled from the Democratic Republic of Congo. As a result, many were left without papers or passports. Yet, amazingly, many people were willing to hand over, for a few instants, their last remaining possessions — a beloved watch; vials of insulin — so that James could photograph them.

Some people we met were even eager to show us what they carried: cell phones or digital cameras with photos of loved ones who they had been separated from during the journey. These devices, and the photos on them, held their greatest hopes of being reunited with a missing mother, a lost son or a wife, two-months pregnant and nowhere to be found.

Of course, there were also several people who were initially mystified by our assignment. Why did James want photographs of old clothing or an ordinary phone charger? But once he explained that we wanted to capture what they thought was worth holding on to throughout the grueling and often dangerous route into Europe, people got it and recounted in even greater detail the stories behind their objects. And even if they still didn’t quite understand our interest, many refugees would still hand over their bags with a smile, before they went on their way, onto the next leg of their journey.

James Mollison is a commercial and documentary photographer based in Venice, Italy.

Caroline Smith, who edited this photo essay, is a special projects editor at TIME.

Megan Gibson is a writer for TIME based in London. Follow her on Twitter @MeganJGibson.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com