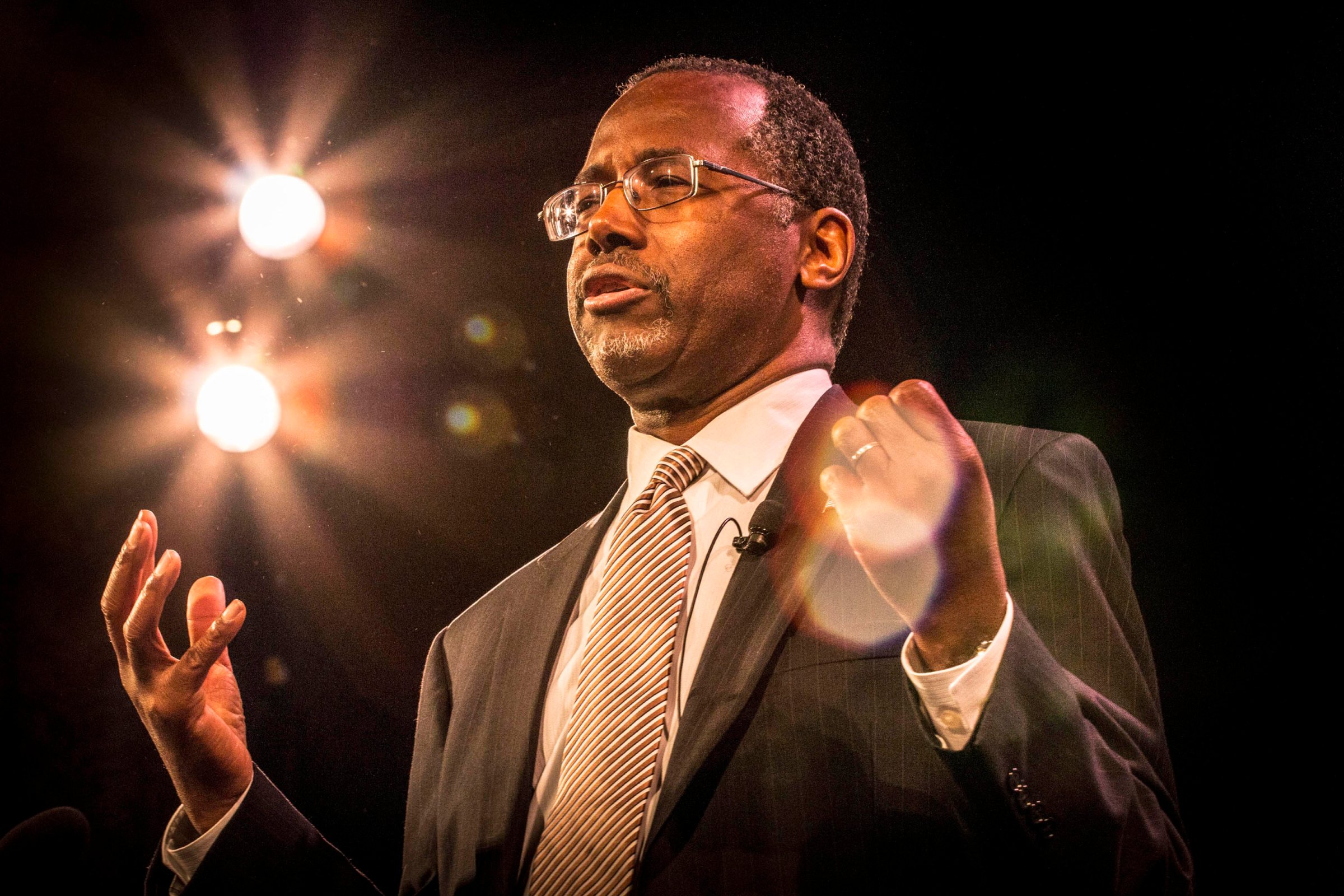

Ben Carson remembers how he cut a small hole in the man’s head and began poking around. He was hunting for a tumor in the patient’s brain stem, trying not to nick anything as he went. “Obviously, you have to be spot-on,” the Republican presidential candidate told TIME as he recalled the procedure over a recent lunch in Nantucket, Mass. “All of this is really being done by feel.”

The surgery came with a 50-50 chance of death, Carson estimated, but there would be certain death if nothing were done. He found the tumor, and moments later the electrical response in the patient’s brain flatlined. “I told you this was a mistake. I told you you shouldn’t have done this,” Carson said the anesthesiologist told him. “You killed him.” Carson, a former head of pediatric neurosurgery at Johns Hopkins, who has a remarkable talent for staying calm under stress, set the comment aside and continued to operate.

That night, Carson left the hospital in a somber mood, with the tumor out but his patient in intensive care. The next morning, the patient was cracking jokes. There was no simple explanation for what had changed. There seldom is in neurology.

The lesson for Carson lies at the core of who he is and what has taken one of the most celebrated doctors of his generation on a most unlikely journey, as a presidential candidate with no political experience. He is now polling just behind Donald Trump in national polls of Republicans. “God gets the credit for all the things I do,” he explains, picking at a salad and sipping lemonade. “But he also gets the blame. My job is to do the best that I can do.”

That just about sums up why, at age 63, he decided to jump into politics, a vocation he never sought and still says he would rather not pursue. It helps explain how he has maneuvered a packed political field with rare calm and little bluster. Carson is a man of science and a man of God, a man who is as familiar with poverty as he is with the halls of Yale University or the corporate boardroom. It’s these seeming contradictions that have carried him this far. “Lord, you know I don’t want to do this, but if you open the doors I’ll do it,” Carson says, recounting his prayers about whether to become a candidate.

Voters–or a higher power–seem to be responding. Carson is drawing robust crowds and millions of dollars in small donations by breaking all the rules of traditional campaigns. He keeps a modest campaign schedule. He is a stilted public speaker and unpolished campaigner. His appeal is one of the mysteries of the 2016 race. “Obviously,” Carson says of his prayers to God, “he’s opening the doors.”

Such evangelism has long found a home among GOP candidates, but its vessels have been former pastors, such as Pat Robertson in 1988 and Mike Huckabee in 2008 and again today. Carson has been driven by a more private faith while capturing the public’s imagination with his achievements in medicine.

He has been declared a “living legend” by the Library of Congress and has received 67 honorary doctorate degrees. In 1987, he led the first successful surgery to separate twins conjoined at the head, a 22-hour endeavor. “I said, ‘Boy, this could really be something that could inspire a lot of kids,'” he says, nodding to the rarity of a black lead surgeon on such a high-profile case. “No one actually knew that I was the primary surgeon until after the operation was over.”

His transformation from public intellectual to conservative hero began when he challenged President Obama at the National Prayer Breakfast in 2013. Standing feet from the President, Carson ripped into the Affordable Care Act and government spending. After that, conservatives urged him to make a run.

Carson’s political positions are a close match for the GOP’s deeply conservative voters. He opposes same-sex marriage, wants to replace Obamacare with health savings accounts and suggests a taxation plan that draws inspiration from Scripture and is a political version of tithing. On immigration, he would allow undocumented immigrants to get legal status only after leaving the country and demonstrating employment.

On the campaign trail, however, he has tripped at times while learning the terrain of a field that is often unforgiving. Carson is given to sweeping statements; his aides have encouraged him “to be a little more circumspect.”

Take vaccines. During the CNN Republican debate in September, Carson was pitted against Trump in an argument about childhood vaccines. Carson was quick and correct with the science: “There have been numerous studies, and they have not demonstrated that there is any correlation between vaccinations and autism.” But then he hedged, saying, “There should be discretion” in certain vaccine schedules and “a lot of this is pushed by Big Government.”

Frank DeStefano, director of immunization safety at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, says that the immune system can handle up to 100,000 vaccines at a time and that there is no scientific basis for a delayed schedule. Carson now says his debate answer was not really about the science. “There can be an emotional issue to it,” he says of parents who are concerned about giving their children vaccines. “We need to consider people’s feelings.”

Carson has also departed from the scientific community on global warming. NASA says 97% of climate scientists agree that trends are due to human activity, but Carson says it isn’t about the data. “It doesn’t matter about global warming or global cooling,” he says. “We have a responsibility to take care of it [the earth].”

Then there’s evolution. Critics note that Carson suggested in 2011 that Charles Darwin was inspired by Satan to come up with his theory of evolution. “I would believe that the forces of evil would be looking for a way to make people believe there was no God,” Carson explains. “I have a different take on it … I say that’s proof of an intelligent and caring God who gave his creatures the ability to adapt to their environment so he wouldn’t have to start over every 50 years.”

And there is his claim that going to prison makes inmates gay. In March, Carson argued that homosexuality was a choice, saying, “A lot of people who go into prison straight, and when they come out, they’re gay.” He apologized for the comment within the day.

While many struggle to reconcile such strong faith with such learned science, Carson says one informs the other. “To believe that we evolved with the complexity of this brain from a pool of promiscuous biochemicals during a lightning storm–that requires a lot of faith,” he says. “Way more faith than I have.”

It is something of a miracle that Carson can muster faith at all. Born into deep poverty in Detroit, he pulled himself up through schooling. His mother, who had only a third-grade education, had Carson submit book reports to her each week even though she could not read them. He is open about the anger he internalized as a young man and about attempting to stab a friend. That failed assault led to Carson’s religious awakening, which today is a central piece of his campaign’s message. The poor black child from Detroit would graduate from Yale and the University of Michigan medical school, climbing to become the youngest head of pediatric neurosurgery at Johns Hopkins at age 33.

He won seats on corporate boards: Costco Wholesale Corp. for 16 years, the Kellogg Co. for 18 years. There, he cultivated a reputation as a quiet, data-driven peer. He had little interest in internal politics, preferring to voice his concerns to management at private quarterly meetings. “He was able to take into account multiple perspectives,” Kellogg CEO John Bryant recalls. “He was very calm.”

Carson also had a keen interest in fiber content in the cereals, as well as the nutritional value of the company’s Morningstar Farms line of vegetarian products. It is a long way from his childhood, when his mother would take the family to farms on weekends with a simple proposition for landowners: The Carsons would harvest four bushels of apples or corn, and the landowners could keep three if the Carsons could take one home to put meals on the table.

“Knowing what a lot of people are experiencing and knowing how I managed to escape, I want people to benefit from that,” he says. Carson is using his campaign’s stage to preach that message wider, drawing a phone call from Kanye West. The two discussed how the rapper could use his music to “help young women in particular realize their self-worth,” Carson says.

Through this tumultuous campaign, Carson has seldom appeared flustered. He says his trick is simple: when under fire, he pictures his critic as “a cute little baby.”

Those who have known him during his days as a surgeon are not surprised. Surgeons have famously short tempers, losing their patience during operations when things don’t go as planned. Not Carson. He knew how to handle the hiccups, says former student Gary Hsich, who doesn’t agree with Carson’s politics. “He’s straightforward and very honest,” says Hsich, now at the Cleveland Clinic. “Recently, some of his honesty seems to have gotten him in trouble. He’s not a smooth talker like the other candidates.”

That’s for sure. In recent weeks, Carson has struggled to explain his repeated statements that a devout Muslim should not be President. That view runs counter to the Constitution, which expressly forbids any religious test for candidates. Voters this year are willing to overlook such incorrect statements and are eager to reward candidates who pledge to avoid politically correct assessments of what ails America. Just look at Trump, who catapulted to the front of the race by infuriating Latino voters, a move that pundits saw as a death knell.

Like Trump, Carson does not fit into a simple box. And his primary selling point is his acclaimed intelligence. “He’s incredibly brilliant in so many different areas and fields,” said Lorraine Goodrich, a 68-year-old retired Marine and Carson supporter who attended a recent event in Sterling, Va. “That mind is so impressive.” Elsewhere in the high school gymnasium, Pat Sullivan was enjoying her second Carson rally this year. “He’s a brain surgeon,” explained the 68-year-old retired nurse from Tucson, Ariz. “You don’t get any higher than that.”

These aren’t his only devoted fans. Carson has inspired a flock of followers on social media, recently surpassing Trump in Facebook backers. Supporters named his campaign bus the Healer Hauler and have donated money to have their children’s names written on its side.

Should his campaign eventually fail–and most do–Carson seems to have already made peace with that as part of God’s plan for him. After all, Carson never wanted to run for President and certainly did not ask for the scrutiny that comes with it. Instead, he says, he will retire. “I would continue to write books, continue to do public speaking,” he says, “probably get involved once again in corporate America, learn how to play the organ.” For someone who made his name rummaging through brains finding tumors by feel, a Bach prelude could be easy.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Biden Dropped Out

- Ukraine’s Plan to Survive Trump

- The Rise of a New Kind of Parenting Guru

- The Chaos and Commotion of the RNC in Photos

- Why We All Have a Stake in Twisters’ Success

- 8 Eating Habits That Actually Improve Your Sleep

- Welcome to the Noah Lyles Olympics

- Get Our Paris Olympics Newsletter in Your Inbox

Write to Philip Elliott at philip.elliott@time.com and Tessa Berenson Rogers at tessa.Rogers@time.com