This week marks the 25-year anniversary of one of the movie industry’s greatest failures: the NC-17 rating. Designed to allow a special place at the cineplex for explicit movies that had more on their minds than just sex, it has had the practical effect of making such movies very difficult to actually watch.

The Motion Picture Association of America, a group that lobbies on behalf of Hollywood and rates films based on general acceptability, had good intentions when it introduced the rating for the Uma Thurman film Henry & June in 1990. The film was certainly sexual, but given that it assayed the lives and loves of Henry Miller and Anaïs Nin, no one could accuse it of being pornography, the sort of film that deserved an “X” rating. The solution seemed clear. Get rid of “X” and replace it with something that would keep kids out while attracting sophisticated, mature audiences. The MPAA’s president, Jack Valenti, cited the history of edgy film classics in announcing the new rating, which forbade attendance by those under 17: “We are going back to the original intent of the rating system. We have an adults-only category and anybody who wants to go see [an NC-17-rated] film can go see it, period. It takes us back to the days, hopefully, of Midnight Cowboy, Last Tango in Paris, and A Clockwork Orange.”

Those three films had been released with an X rating before the category came to be seen as tantamount to porn. But, despite the high-minded aims of the ratings board, history repeated itself swiftly after Henry & June’s release. By 1992, Tri-Star, nervous about losing out on potential box-office from teen moviegoers, insisted on editing the thriller Basic Instinct to reach a wider audience; TIME quoted the chairman of Universal as saying “NC-17 movies do not fit into our main business plan.”

Universal, along with the other studios seeking to avoid a rating that had once been heralded as a gift to cinema, had good reason to fear. A few months after the rating was announced, Blockbuster (then a giant in the world of movie rentals) declared they would not carry any NC-17 films; the rating, they said, was effectively the same as X had been, and they’d never carried X-rated films. Some movie exhibitors had a similar policy. Even if an audience for smart, adult movies were out there, it remained difficult to reach them.

So, NC-17 quickly gave rise to a death spiral of sorts. Studios didn’t want to produce movies whose status in the marketplace would be so uncertain, and thus there were precious few data points to prove that NC-17 movies could, indeed, be high art. Furthermore, the films that seemed most often targeted for NC-17, as TIME reported in 1994, seemed, consistently, to be explicitly sexual rather than explicitly violent, meaning that the MPAA was meaningfully defining mores.

This trend has only intensified in the years since.

Case in point: 1999’s Eyes Wide Shut, the Stanley Kubrick erotic thriller whose subject matter lends itself perfectly to a rating for discerning adults only, got its most explicit moments edited down to ensure it got an R. Surely the number of teens eager to see a nearly three-hour fugue about the desperation of married New Yorkers could not have seriously affected the film’s bottom line, but the idea that Warner Bros. would be sacrificing entire theaters and real estate on Blockbuster shelves was too much to bear. Even after Blockbuster’s dominance ended, the NC-17 label was a badge of dishonor. The 2011 film Blue Valentine, for instance, was slapped with an NC-17 rating that its backers appealed, proving that they’d rather avoid a label that had once been intended as a sign of sophistication.

One of the late critic Roger Ebert’s most significant crusades was to retire the NC-17 rating for mainstream film, as X had been retired before it, and develop an “A” rating for movies intended only for adults. As Ebert wisely saw, the problem in 1990 was that NC-17 had replaced the old X but had never been meaningfully distinguished from it. In his scheme, “X would remain to denote hard-core. ‘A’ would allow adult movies of redeeming artistic or social merit to escape the curse of the X,” he wrote. Maybe the addition of some gradation, enabled by keeping both options around simultaneously, might have helped a number of sophisticated films over the past quarter-century escape cuts. But given what happened 25 years ago, when the MPAA introduced a new standard whose resulting stigma looked precisely like the old one’s, this might be too much to wish for.

Rather, the hope for cinema’s mature, sophisticated future comes from elsewhere. In recent years, two films have shown that things just might be changing. In 2011, Shame, a movie about sexual compulsion that no reasonable cuts could have rendered suitable for kids, managed to get one of the top debuts ever for an NC-17 film. It was a limited sample size, but Fox Searchlight, the studio behind Shame, promoted the film aggressively rather than acting cowed. Then, the highest-profile NC-17 film in recent years, Blue is the Warmest Color, the 2013 Cannes Palme d’Or winner, succeeded not because it was marketed to adults but because exhibitors decided to make a one-time exception for the film; Cinemark screened the film in a break with historical policy, and New York City’s IFC Center “selectively enforced” the ban on children attending.

The successes of Shame and Blue don’t show that NC-17 is becoming safe territory for ambitious filmmakers. The default setting for an NC-17 film, without a serious campaign to prove it’s something other than pornography, is still irrelevance. But the Internet’s power to spread entertainment beyond the controlling aegis of theater and rental chains, and chains’ willingness to break their own rules once in a while, signal that the future of adults-only entertainment may come from breaking the rules, not making new ones.

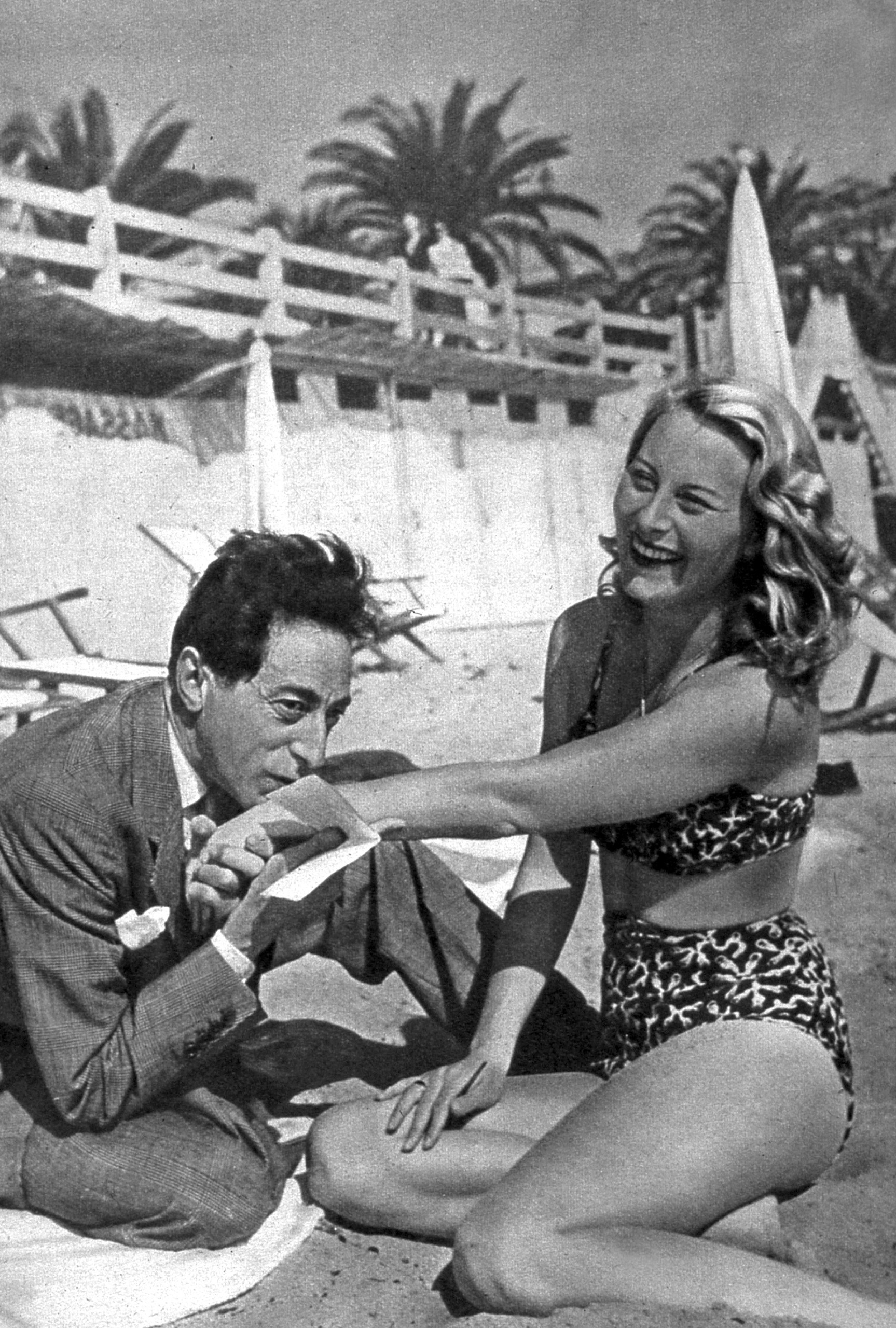

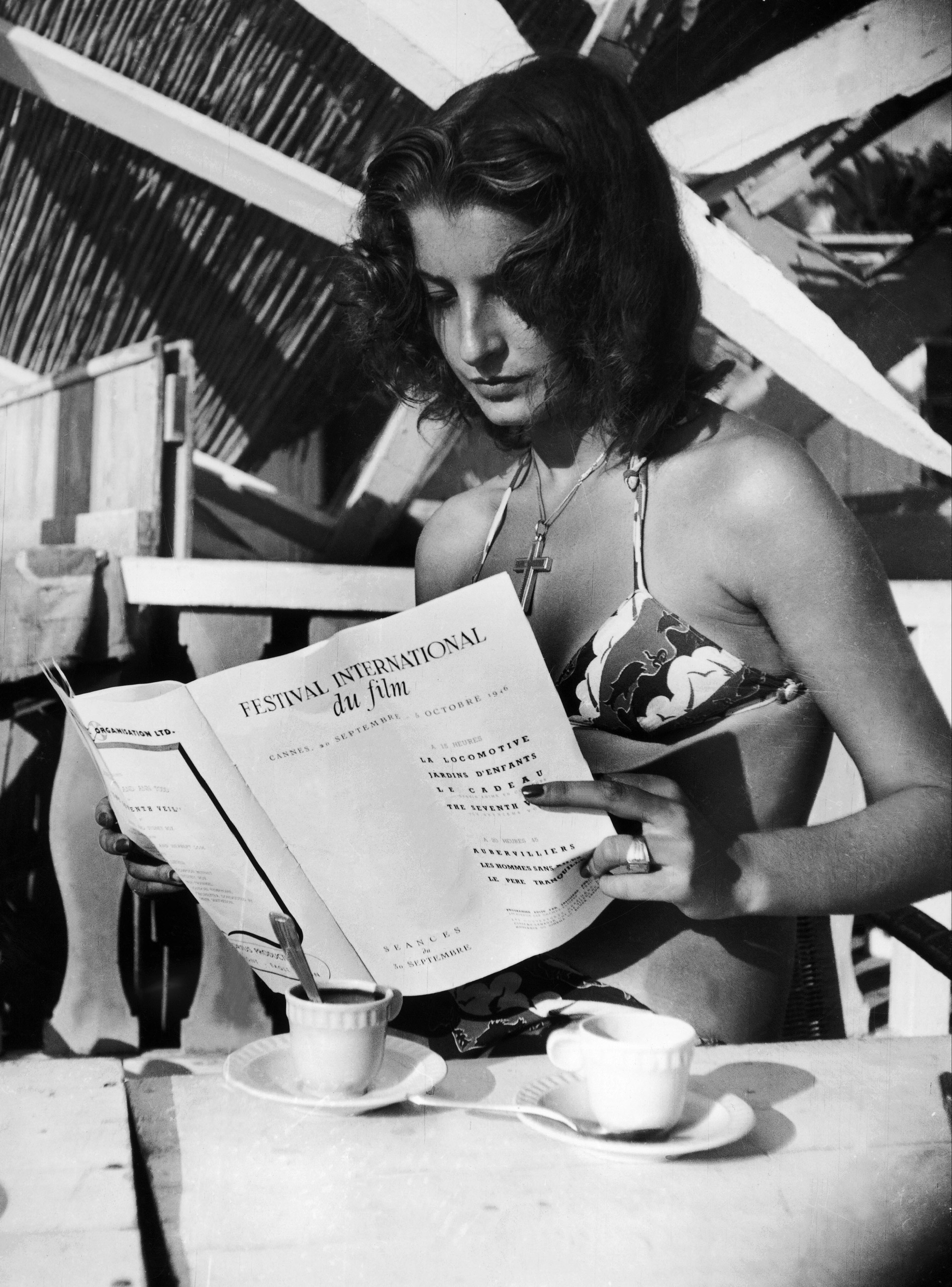

The First Cannes Film Festival

More Must-Reads from TIME

- How Donald Trump Won

- The Best Inventions of 2024

- Why Sleep Is the Key to Living Longer

- Robert Zemeckis Just Wants to Move You

- How to Break 8 Toxic Communication Habits

- Nicola Coughlan Bet on Herself—And Won

- Why Vinegar Is So Good for You

- Meet TIME's Newest Class of Next Generation Leaders

Contact us at letters@time.com