Correction appended, Oct. 9

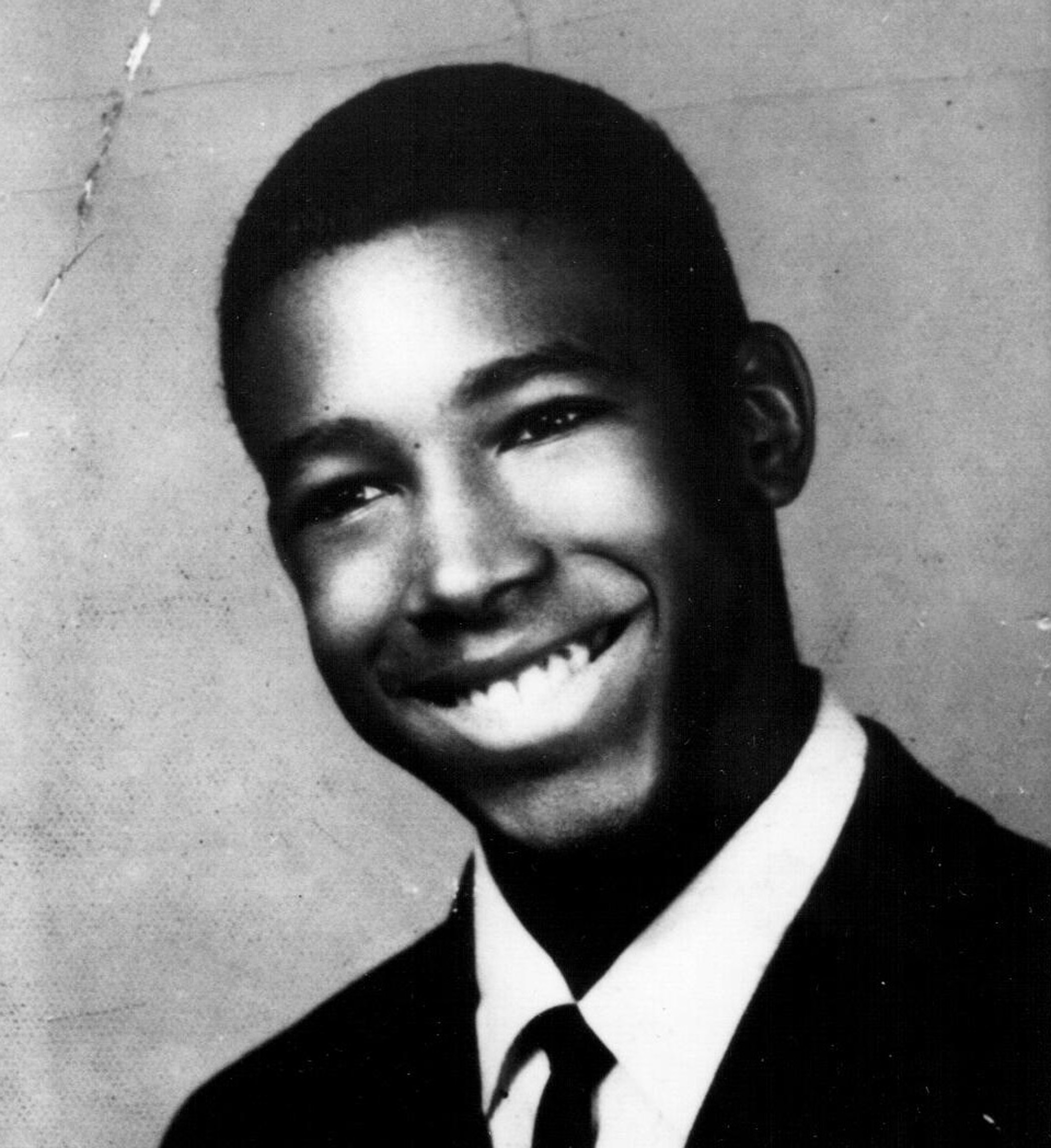

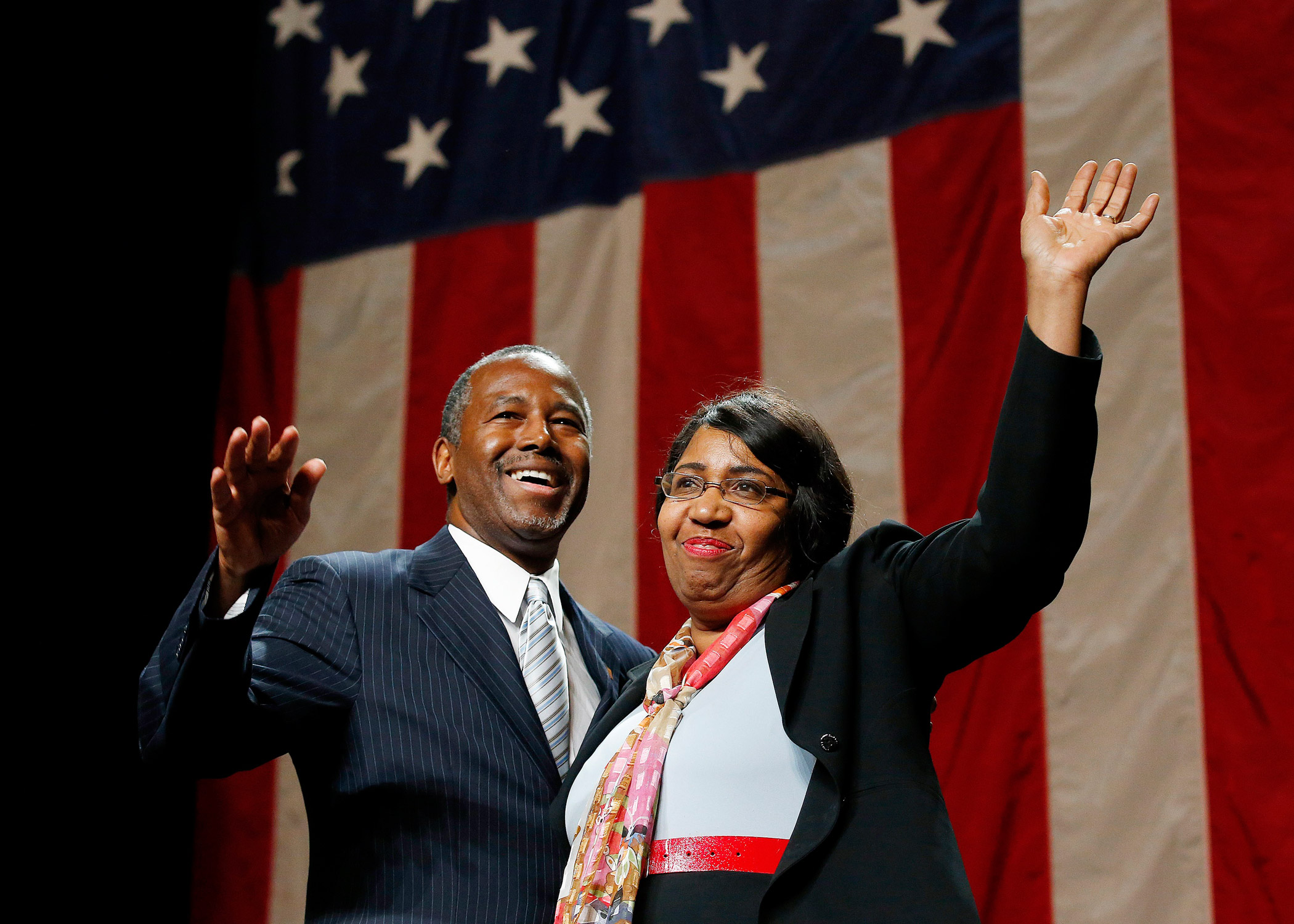

Long before he was a leading candidate for the Republican presidential nomination, Ben Carson was a folk hero to the black community.

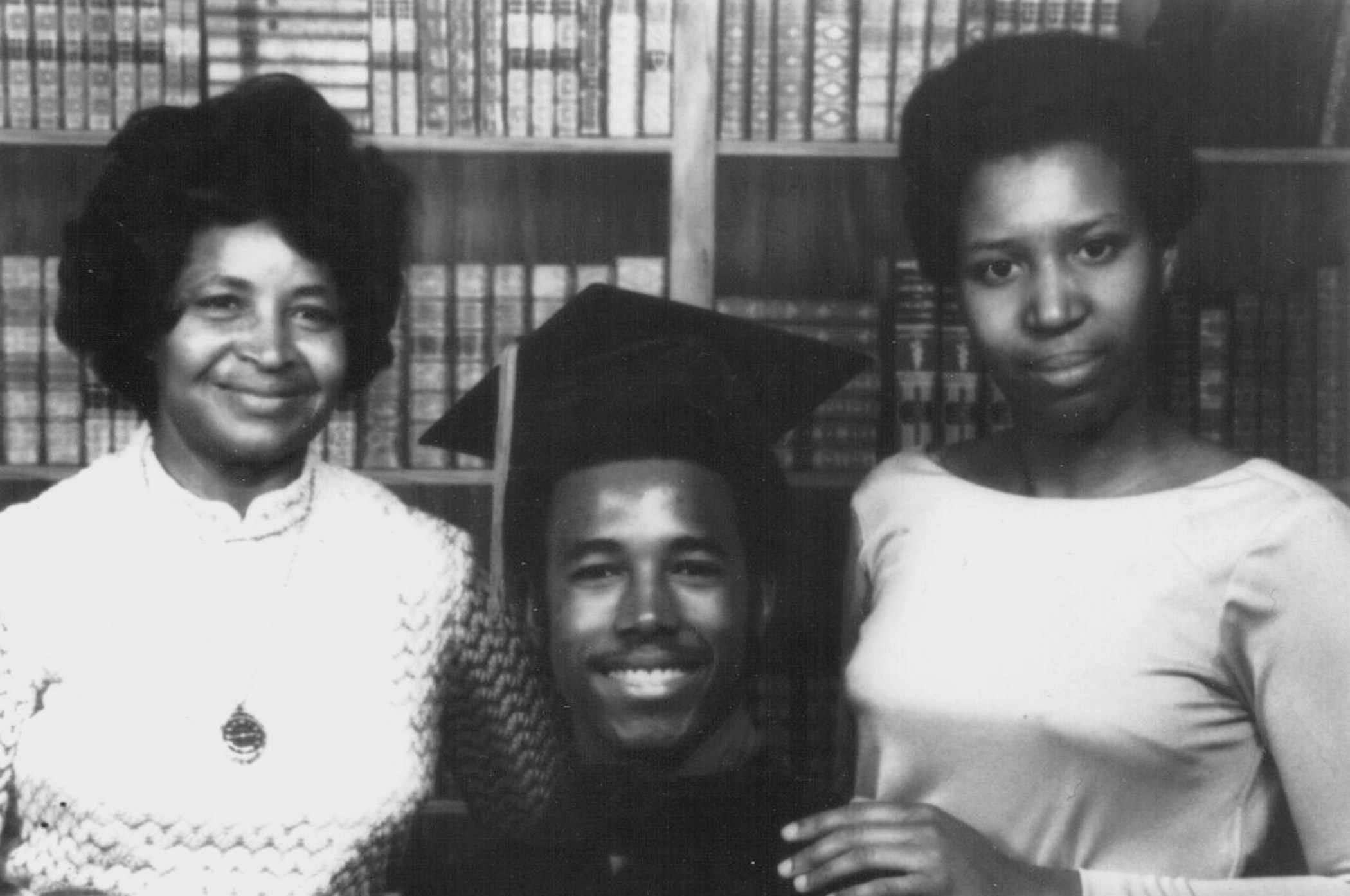

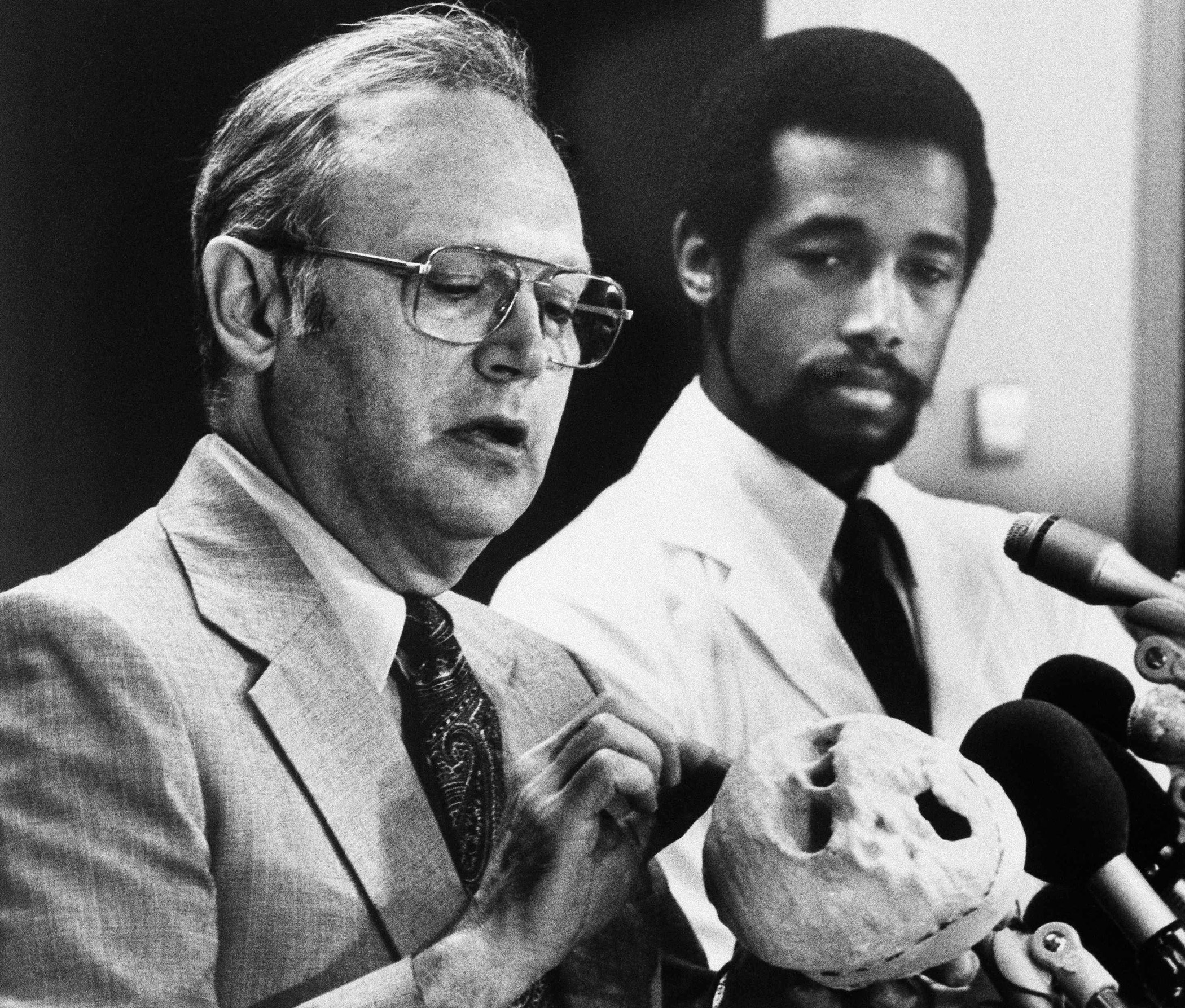

It was a classic American story: He had risen from poverty to become one of the nation’s top pediatric neurosurgeons, successfully separating twins conjoined at the back of the head for the first time in a dramatic 22-hour surgery, among other achievements.

Carson’s fame was due in large part to his 1992 autobiography, which became required reading for many young African-Americans.

Dwight Watkins, an African-American author from Baltimore, first read Gifted Hands as an assigned book in high school in the late 1990s. Carson, who also ran a scholarship fund for inner-city students, later came to his school for a visit. Watkins, who grew up in Baltimore’s rugged east side, where drugs and violence are a reality, remembers feeling inspired by Carson at the time.

“It meant something to me—I felt like he was a guy who made it,” he said. “If he could do it, I could do it.”

Watkins did make it—though he stumbled for a while, including a stint as a drug dealer, which he now writes about in essays. But as Carson has moved up in the Republican primary polls in recent weeks, Watkins has come to revisit Gifted Hands as an adult. He now sees it much more differently, telling a local newspaper that he views it as fiction.

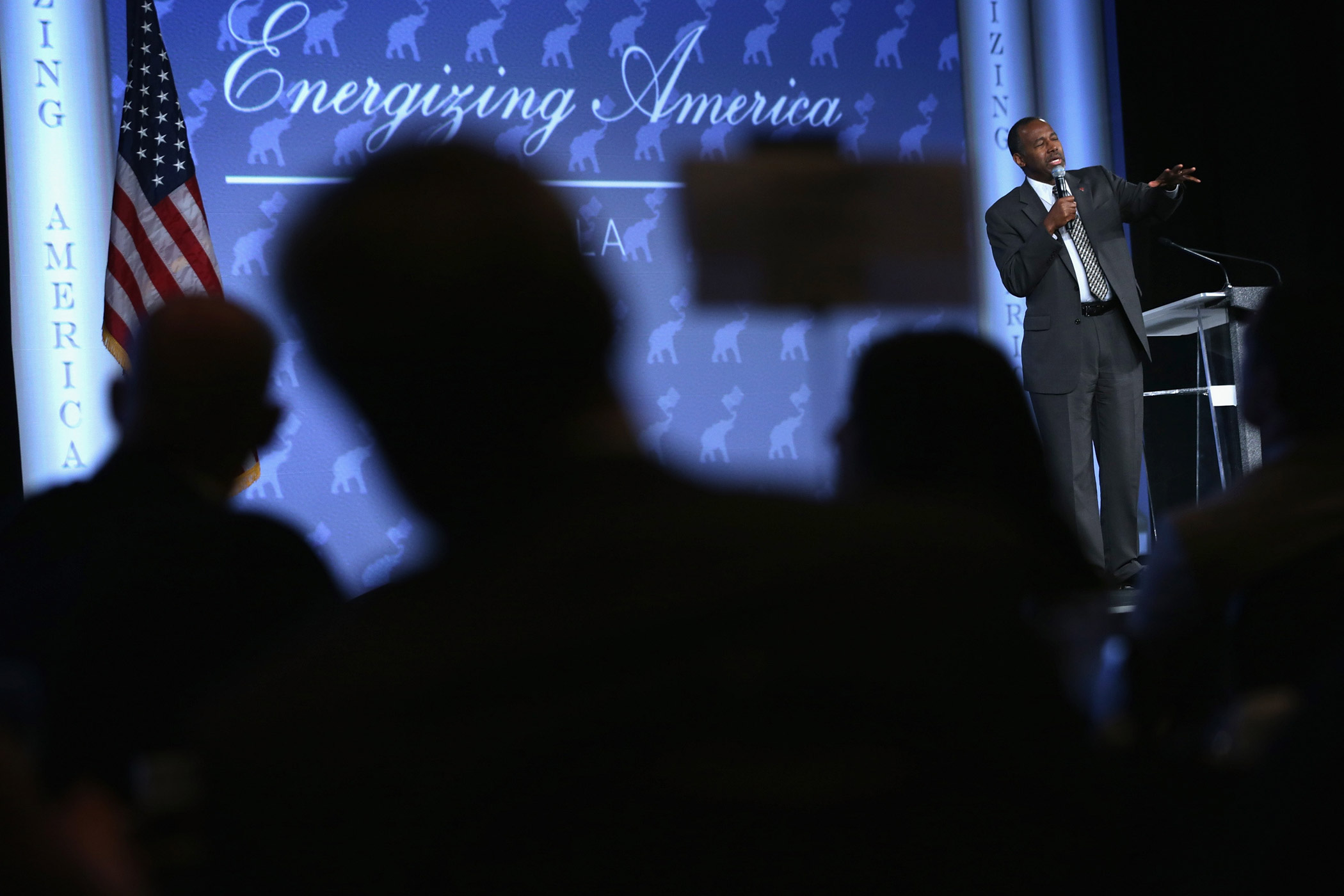

He’s not alone. In recent years, Carson has found new fame with a different audience, primarily evangelical Christians and conservative Republicans who are backing his campaign. But that has come at a cost, as many in the black community now view him unfavorably.

That’s in part because Carson has been outspoken in his opposition to President Obama, whom he has called a “psychopath,” an anti-Semite and the “divider-in-chief.” It’s also due to the conservative tenor of his political views, which include comparing Obamacare to slavery, a strict stance on abortion and recent comments about Muslims being eligible to run for president.

But the campaign has laid bare a tension that was present all along. When Carson was telling his life story in his book, and later in a movie of the same name, it was viewed as aspirational, something like a self-help book. But when he began telling those same anecdotes in the context of a campaign, many African-Americans viewed it as validating conservative views on poverty that they disagree with.

Read More: Inside Ben Carson’s Unlikely—and Uncommonly Spiritual—Campaign

Dr. Leah Wright Rigueur, author of The Loneliness of the Black Republican, a history of 20th century African-American conservatism, says that many in the black community view people like Carson differently depending on whether they are speaking within the community or to the broader public.

Although they may not have agreed with some of his more conservative beliefs, Wright Rigueur says they were willing to overlook them, like an uncle who says impolitic things at Thanksgiving. But once he began running for office that changed.

“His conservatism, that’s exhibited in his speeches, was safe, it was private, a conversation among people within the community,” says Wright Rigueur, a professor at Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government. “He kind of hadn’t violated the unspoken rule of speaking out of turn.”

In the years after publishing Gifted Hands, Carson spread his message at speaking engagements and through charitable work like his Carson Scholars program. He told TIME that at various times “12 to 15 movie producers” approached him about turning the book into a film, but he wouldn’t agree because they wanted to take some “artistic license” with his story.

When producer Dan Angel came to Carson about making the film, he had to promise to go to battle for Carson and it took years to get TNT to agree to the project. Angel says he and his team at The Hatchery, a production outfit whose goal is to make uplifting content for families, were willing to put their careers on the line for the movie, which helped convince Carson.

Read More: Ben Carson Imagines His Debate Opponents as ‘Cute Little Babies’

“I really wanted something that would truly be inspirational,” Carson told TIME in a recent interview. “We went on the set and Cuba [Gooding Jr.] and everybody said you know, this is not a job for us. This is a mission.”

If the book had been a turning point with his relationship with the black community, the 2009 movie was the beginning of a shift in the other direction. It proved immensely popular with evangelical Christians, according to one of the film’s producers, and is now the No. 1 faith movie on Amazon.

“The movie has made it possible for people to share his story overnight,” said producer Margaret Losch. “Hollywood might not have wanted the movie, but there is a large faith community around the country.”

Although many of the themes in Carson’s speeches have remained the same over the years, the emphasis has shifted. In 1997, when he was invited to speak at the National Prayer Breakfast, he made self-deprecating jokes and talked about his life story.

When he returned to the event in 2013, the outline remained the same, but he went further, describing conservative ideas for health care and tax reform while standing just a few feet from President Obama.

The speech attracted a new audience to Carson, which was fed by other speeches and interviews in which he became even more political, often using harsh language, such as the time he referred to Obamacare as the worst thing since slavery.

Read More: Ben Carson Says Muslim Comments Were Taken Out of Context

The newfound attention was enough to land him as a runner-up on Gallup’s annual “most admired man” list in 2014, alongside the likes of Stephen Hawking, Bill Gates and Bill O’Reilly.

Since his presidential campaign launched in May, Carson has jumped to second place in the polls, after Donald Trump. But much of his support draws on white voters, who backed him by 57 percent in a head-to-head against Hillary Clinton in a hypothetical matchup in a recent Quinnipiac poll, compared to just 18 percent of black voters.

For black conservatives such as Rita Davenport, Carson is a gift. She has been “all in for Ben” since February 2014, when she discovered the Carson SuperPAC on Facebook. “Personally, I like what he says and it sounds like what I believe,” said Davenport, who has campaigned for Carson in Des Moines, Iowa. “He’s at the top, pinnacle of his field, and he’s listening to people telling him to run putting aside his own personal happiness to run.”

But for Watkins, Carson’s new success among conservatives contains an element of betrayal: “To a certain extent, it’s still a good story, I just disagree with his politics. It’s almost like I don’t believe it when I hear him talk.”

Read Next: Why Ben Carson Is Running for President

Correction: The original version of this story incorrectly described Ben Carson’s breakthrough surgery. He was the first to successfully separate twins conjoined at the back of the head.

See Ben Carson's Life in Photos

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Breaking Down the 2024 Election Calendar

- How Nayib Bukele’s ‘Iron Fist’ Has Transformed El Salvador

- What if Ultra-Processed Foods Aren’t as Bad as You Think?

- How Ukraine Beat Russia in the Battle of the Black Sea

- Long COVID Looks Different in Kids

- How Project 2025 Would Jeopardize Americans’ Health

- What a $129 Frying Pan Says About America’s Eating Habits

- The 32 Most Anticipated Books of Fall 2024

Contact us at letters@time.com