It was once a test conducted by doctors, requiring an appointment for an office visit. So in the mid-1970s, with the invention of the home pregnancy test, a woman’s path to finding out if she was going to have a baby made a revolutionary new course correction.

Even after a process was developed to detect a pregnancy through the reaction of a woman’s urine to animal reagents, the tests were still done in labs, and results were sent to the doctors’ offices, who then would notify the patient by telephone or mail. The entire exercise could take up to two weeks.

Margaret Crane, a 26-year-old freelance graphic designer who was working at the now-defunct pharmaceutical company Organon, in West Orange, New Jersey, saw hundreds of pregnancy tests that doctors had sent in from their offices in the company’s lab.

Crane, who designed packages for lipsticks and ointments for Organon, remembers thinking, “It’s so simple, just a test tube and a mirrored surface. A woman could do that herself.”

“It just came to me just like that,” she says, “I tried to think of a way to make this happen.”

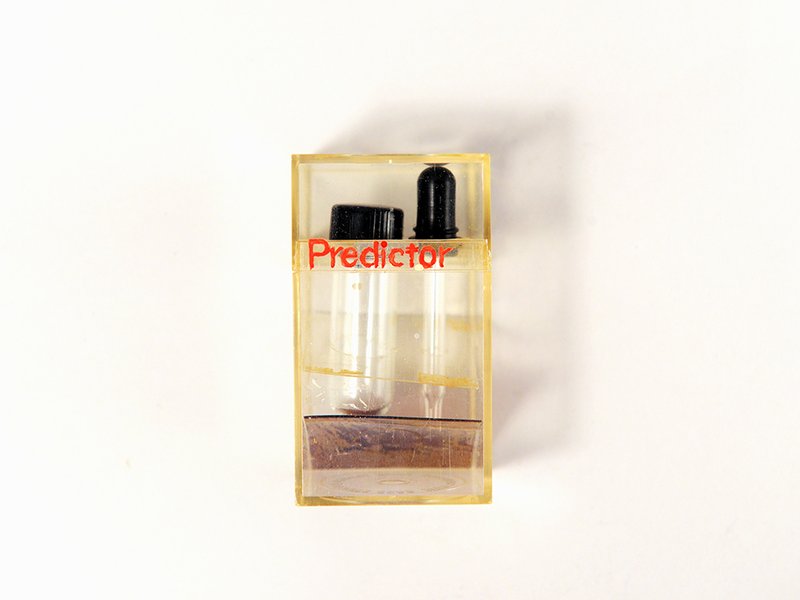

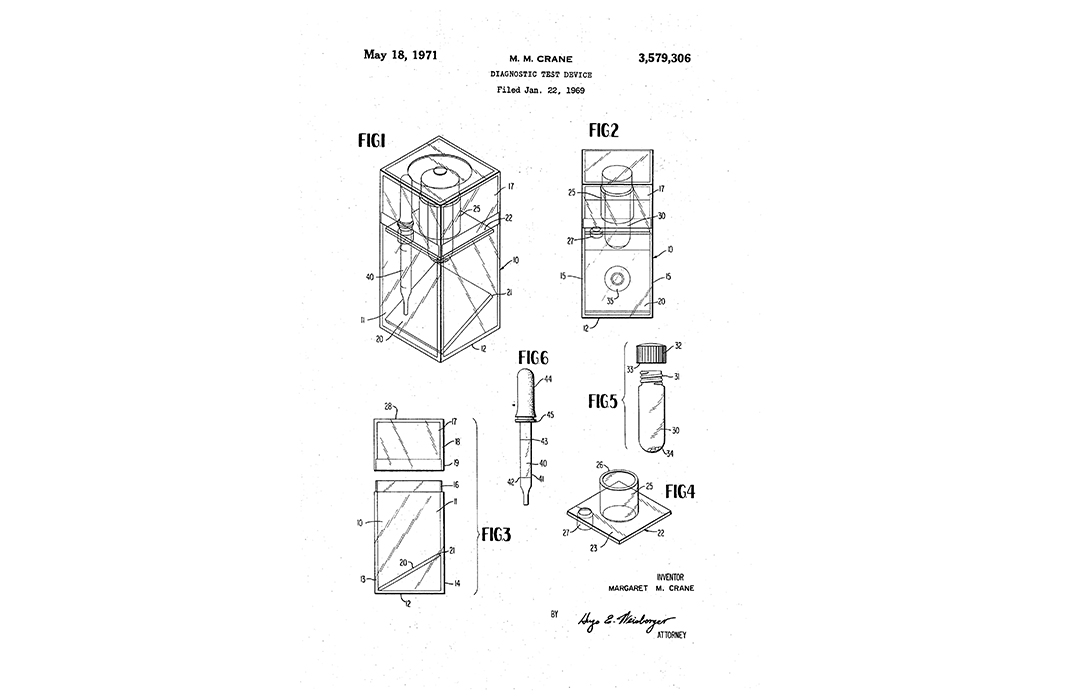

She wasn’t a scientist and had no particular chemistry background. But after trial and error, she created in 1967 a prototype home pregnancy test, packing the necessary contents into a stylish plastic box, modeled after a paper clip container on her desk. It looked like a toy chemical set with its dropper, vial, rack and mirror.

That early device, which she called the Predictor, was recently acquired by the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History, after it was auctioned last spring along with one of the first finished products that went to market a decade later. (“Keep refrigerated,” said a warning label on the box.)

Today, home pregnancy tests are quick and easy. Popsicle stick-size devices give an answer just moments after detecting (or not detecting) human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG), a hormone secreted during pregnancy, in a woman’s urine. The early model works on the same principle, but with more moving parts. Yet it delivered results in just two hours, rather than two weeks.

“I knew this just had to happen,” Crane says.

As Crane told a curator at the auction house where the prototype went up for sale, “A woman should not have to wait weeks for an answer.”

There wasn’t a lot of enthusiasm for the idea at first, she recalls. “Just the opposite, actually.” The company was worried it would lose its lab business to doctors if everybody tested themselves at home. “But I really persisted. I thought this is a necessary thing.”

It was the corporate owners in the Netherlands who thought Crane’s idea was worth test-marketing. Other designs were sought and brought in to compete with Crane’s.

“Some of them had little flowers around the edges, or had purple diamonds, things like that. They had gushy plastic. They were not sturdy. One had a tassel at the top,” Crane says. “They didn’t look scientific. If I were a [customer], I’d worry about how accurate they could be.”

Ira Sturtevant, an ad man, came in and immediately selected Crane’s elegant design. The two would become partners, professionally and otherwise, for more than 40 years, until his death in 2008.

The pair started their own design company Ponzi & Weill and devised the marketing campaign for a test run in Canada. “Every woman has the right to know whether or not she is pregnant,” said an early ad for the test that women “can do it by yourself, at home, in private, in minutes.”

Because of Food and Drug Administration rules for medical devices, it took a while to get approval in the United States — not until 1976. Even though Crane’s name was on the patent for the device, which Organon licensed to companies that bought e.p.t., she still didn’t get a penny for the design for the Answer and Predictor as it came to the U.S. market in 1977.

“I had to sign off my rights for a dollar,” she says. “And I never got the dollar.” She didn’t mind. She was happy to get the business for the marketing campaign—and to have met her partner in the process.

It was only when the New York Times Magazine ran a short “Who Made It?” feature on the home pregnancy test in 2012 and omitted her work, her niece urged her to make her story better known.

“I still had the prototype. What was I going to do with it? It had to be somewhere. If somebody cleaned out my apartment after I died, they’d think what is this and throw it away.”

“What Crane did is really revolutionary,” says Alexandra Lord, chair and curator of the division of medicine and science at the American History Museum. “It enables a woman to learn that she’s pregnant on her own terms in her own home. So it takes away from learning about it from your doctor.”

Though some at the time mocked its development, Lord says, “in terms of its target audience, which was women who were wondering if they were pregnant or not, it was extremely appealing.”

It even earned a spot in pop culture, featured prominently in the first episode of the detective drama “Inspector Morse” (at about 14:40 in this clip.)

“People in the company told me in effect that I was evil, this was really bad, this was terrible, and I had no right to be bringing this up—and women had no right to be doing this themselves; this was in doctors’ hands,” Crane says. “And apparently some doctors were very upset about it when it finally got to the market, but not for terribly long.”

Rapid sales showed that most women were happy about the product.

“I haven’t heard anything negative about it from women,” Crane says, though men at the company had been upset with her. “I never quite knew why. I don’t understand why somebody should be so unhappy about a person knowing this themselves.”

Besides, she said, every insert to the kit urged women, if they were pregnant, to immediately see a doctor for care. “That was my hope at any rate,” she says, “to get people to know their condition and start taking care of it.”

Having such knowledge earlier changed pregnancy itself, says Lord. “Previous to the development of the home pregnancy kit, women might experience a miscarriage very early on, and they didn’t always know they were pregnant.”

Lord says she doesn’t know when the device will go on display at the museum. “It’s an American innovation story, but it’s also part of medical and science, as well as home and community life,” Lord says, just to name three disciplines that the museum’s historians and curators pursue.

But, she says finally that she’d like to see it displayed in the museum’s new show American Enterprise that traces the development of U.S. commerce, “I think it’s part of the story. This is an invention developed by someone to be marketed, and it really changes how people view pregnancy.”

Crane, who at 75 still designs two days a week, says she’s happy the device has found its home in the Smithsonian collection. “It’s really thrilling,” she says.

This article originally appeared on Smithsonianmag.com

More from Smithsonianmag.com:

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Inside Elon Musk’s War on Washington

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Cecily Strong on Goober the Clown

- Column: The Rise of America’s Broligarchy

Contact us at letters@time.com