Much of the rest of the democratic world seems perplexed or bemused by America’s lengthy presidential political season. (The UK boasts only one month of official campaigning for prime minister.) But our endless campaign for president has the same advantage of any long courtship: we see our suitors in so many different situations that they can’t hide all their flaws. The guard comes down and the truth comes out. America’s prolonged process holds a mirror to the hearts of the candidates, and for some, that mirror has revealed a loathsome heart of darkness.

Unfortunately, the words expressed by these hearts are even darker. What is most frightening is that, under the guise of patriotism, these people in the public spotlight are committing hate crimes. Such irresponsibility calls into question their judgment, their ability to fairly lead or speak for our diverse population, and their professed beliefs about what America stands for.

The U.S. Department of Justice describes a hate crime as “the violence of intolerance and bigotry, intended to hurt and intimidate someone because of their race, ethnicity, national origin, religious, sexual orientation, or disability.” The Bureau of Justice Statistics estimated the number of hate-crime victims in the U.S. to be over 250,000. And, though we cherish our right to free speech in this country, we also acknowledge that we are not entitled to say anything we want when it can cause others to be harmed. When those who have governmental authority, such as police, or who command wide attention from the public, such as candidates and pundits, express contempt for any group, it emboldens the bigots to crawl out from beneath their tree stumps to openly express their prejudices because they believe they have tacit approval from those in authority. Princeton economist Alan Krueger suggests one significant cause of hate crimes is the “official sanctioning and encouragement of civil disobedience.” Hate crimes occur when those in authority create an atmosphere of hate through their speech.

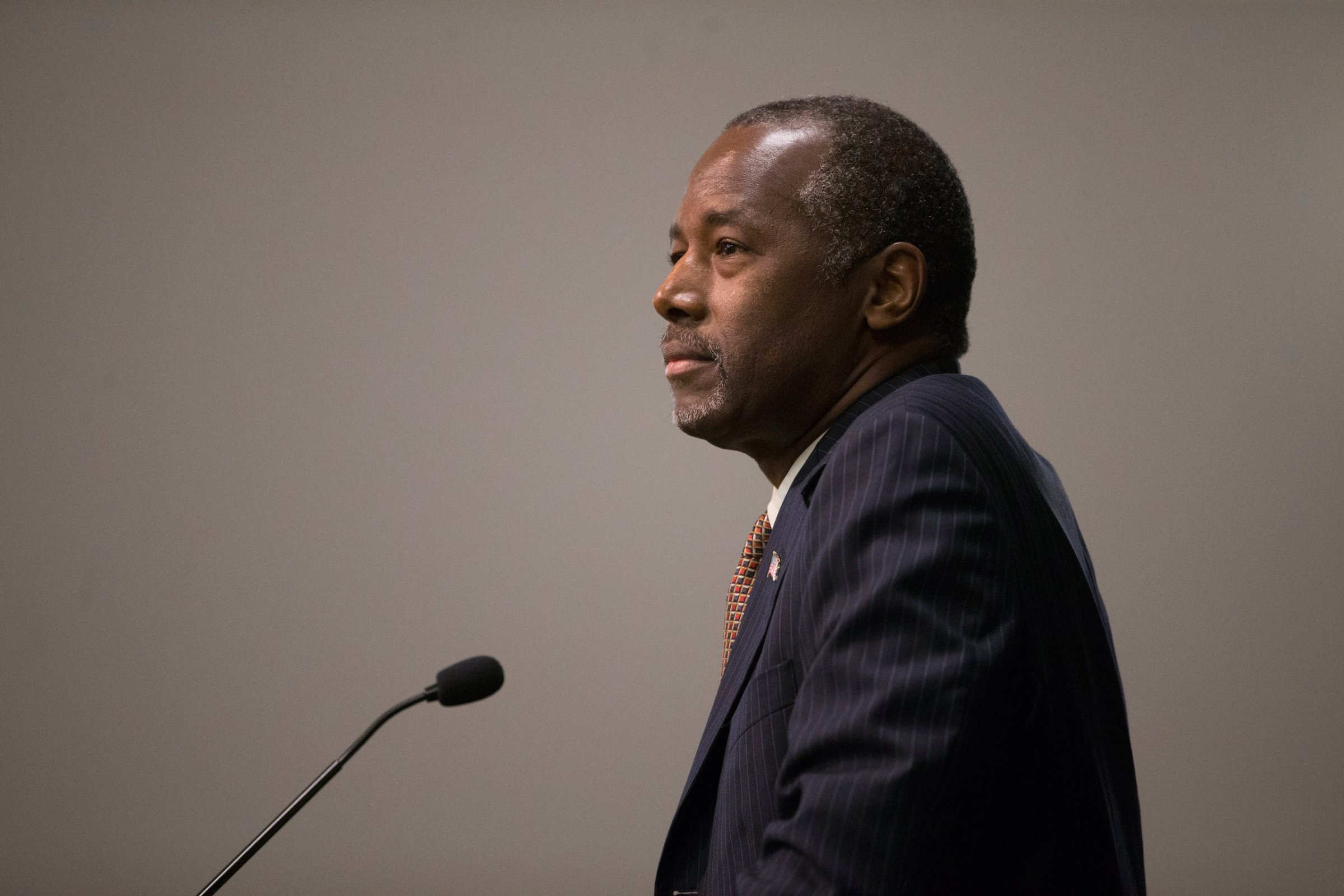

When presidential candidate Ben Carson said, “I would not advocate that we put a Muslim in charge of the nation,” because it was “incompatible with the Constitution,” he made Muslims targets by implying they were incapable of being loyal Americans—an opinion he continued to promote even into a recent CNN interview. Because of him, Muslims are now a little less safe as they walk home. Perhaps even more baffling is that Carson has a book coming out soon that is his common-sense approach to understanding the Constitution. Sadly, his comments are an attack on, rather than a defense of, the Constitution. Article VI of the Constitution states that “no religious test shall ever be required as a qualification to any office or public trust under the United States.” Thomas Jefferson and the boys would certainly be aghast to hear Carson’s Bizarro World interpretation. Carson’s attitude certainly echoes the attacks on John F. Kennedy by Norman Vincent Peale and other Protestants who argued that Kennedy’s Catholic faith was incompatible with being president.

Presidential hopeful Donald Trump has been a deep well of hate speech. What makes it worse is that he doesn’t seem to realize it, which makes us question his perception of reality of what America stands for. First, his June 16 accusation that Mexican immigrants were mostly drug dealers and rapists. The gleeful outpouring of agreement from closet racists, previously afraid or ashamed to openly express their irrational hostility, confirms the terrible effect of such hate speech on society. Even though facts, statistics, and studies by authorities on the subject contradict Trump’s claim, this doesn’t matter to bigots because by definition they have pre-judged people: reached a conclusion without weighing all the facts.

Trump’s second gaffe was in referring to the looks of his rival, Carly Fiorina: “Look at that face! Would anyone vote for that? I mean, she’s a woman, and I’m not supposed to say bad things, but really, folks, come on.” This hate speech goes out to all you men in the audience. After all, he’s saying with a wink and frat grin, we know a woman’s worth is based first and foremost on her looks, not her intelligence or moral fortitude. His statements confirmed the very worst attitudes that have been perpetuated toward women that have helped maintain their lower wages, worse health care, glass ceilings, and physical exploitation.

Even worse, Trump attempted to right his unrightable wrong at the second debate by saying, “I think she has a very beautiful face, and she is a beautiful woman.” His comment showed he had learned nothing from his original insult. Calling her beautiful, or ugly, still emphasizes her looks over her abilities. Trump’s inability to learn from mistakes is a disturbing characteristic for a would-be president.

Trump’s third hate crime is how he dealt with the man who approached him during a town hall event in Rochester, NY: “We have a problem in this country. It’s called ‘Muslim,’” the man said. “You know our current president is one. You know he’s not even an American…. Anyway, we have training camps growing where they want to kill us. That’s my question: When can we get rid of them?” This was a golden opportunity for Trump to demonstrate his presidential savvy, patriotic duty and moral leadership. Instead, he folded his cards: “We’re going to be looking at a lot of different things. You know, a lot of people are saying that and a lot of people are saying that bad things are happening. We’re going to be looking at that and many other things.” Rather than tell the man that Trump did not stand for this kind of paranoid anti-American ranting, he muttered a bunch of nonsense generalities. How will he show a strong hand to foreign leaders when he can’t handle a delusional racist in a Trump t-shirt? More troubling, by not countering this man, he sent out a message of passive agreement that notches up anti-Muslim prejudice another notch.

Trump countered criticism by saying, “Am I morally obligated to defend the president every time somebody says something bad or controversial about him? I don’t think so.” Maybe not every time, but certainly this time in front of a national audience when he had the chance to promote intelligent debate, protect Muslims from bigotry, and establish his moral obligation to defend the country. A few days later, Trump adjusted his opinion saying, “I love the Muslims. I think they’re great people.” He even said he would not be opposed to having a Muslim on his cabinet. While he deserves credit for damage control, the damage was already done.

Conservative pundit Ann Coulter gave anti-Semitism a much unneeded boost when she tweeted her outrage over Republican candidates during the second debate expressing support of Israel: “How many f—ing Jews do these people think there are in the United States?” Naturally, a right-wing group expressed their support through #IStandWithAnn. The notion that Jews wield too much power in politics is so old and musty that it’s almost quaint. It’s interesting that the discussion did not address the political issue of Israel’s value as an ally in the region. Instead of arguing merits, word was sent far and wide across the land: Jews are the problem.

After such controversial statements, there’s always a follow-up explanation in which these nattering nabobs (you’re welcome, Spiro Agnew) “clarify” what they really meant. Unfortunately, by then it’s too late. The damage has already been done. Bigotry has been broadcast like a wireless network (“Can you hear my hatred now?”). Mexican immigrant children, Jewish children, Muslim children, and daughters everywhere will walk among their peers a little more ashamed, more frightened, and more in danger because of their hate speech.

Recently a 14-year-old Muslim boy in Texas brought a homemade clock to school and was handcuffed and arrested for suspicion of bringing a bomb. He was suspended for three days. Since then, the boy has been invited the White House by President Obama and to Facebook offices by founder Mark Zuckerberg, and Microsoft sent him a huge bundle of computer equipment. There’s also been considerable chatter about whether the boy was perpetuating a hoax, criticism that he didn’t invent the radio, and other such blame-the-victim invective that is irrelevant. Commentator Bill Maher agreed with the arrest: “Because for the last 30 years, it’s been one culture that has been blowing sh-t up over and over again.” Maher’s rant completely misses the point: In the United States, we don’t arrest, humiliate, and punish children because they belong to a religion in which extremist members are violent because that would include almost every religion in the country. What we do is calmly investigate, gather information, then act in a rational manner. Was there anything that Ahmed Mohamed ever did so far in school to suggest he might have a bomb? Even if we agree that the teacher and administration acted responsibly in not taking any chances, and a case can be made on their behalf, there’s no justification for the harsh treatment of the boy. His treatment was based on his religion and nothing more, which is about as un-American as it gets.

In that same week, a Chicago Sikh man was brutally beaten while being called “Bin Laden” and “terrorist.” Ironically, being Sikh is not the same as being Muslim. In fact, there is animosity between the two religions in parts of the world. The teenager who perpetuated the crime is just another mindless conduit of hate that burns in this country for anything, anyone, or any idea that is not familiar, traditional, or comfortable. We certainly don’t want leaders who stoke those flames with their dangerous rhetoric.

A favorite movie of mine is Gentleman’s Agreement (1947) in which Gregory Peck plays a reporter who pretends to be Jewish in order to write a story about anti-Semitism. He is socially ostracized, his son threatened, and his engagement nearly destroyed. Defending her own lack of bigotry, his fiancée explains how she was at a dinner where a man told an anti-Semitic joke. The man she’s telling the story to, a close Jewish friend, asks her, “What did you do?” She replies: “I wanted to yell at him. I wanted to leave. I wanted to say to everyone, ‘Why do we take it when he’s attacking everything we believe in?’” “What did you do?” her friend persists. To which she replies, “I just sat there.” The “gentleman’s agreement” is that when people say things that create an atmosphere of fear, hatred, and exclusion, nobody speaks up. In order to end it, to send the pretenders of patriotism back to their caves, we all need to speak up. We never want to have to answer the question, “What did you do?” with “I just sat there.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Introducing the 2024 TIME100 Next

- The Reinvention of J.D. Vance

- How to Survive Election Season Without Losing Your Mind

- Welcome to the Golden Age of Scams

- Did the Pandemic Break Our Brains?

- The Many Lives of Jack Antonoff

- 33 True Crime Documentaries That Shaped the Genre

- Why Gut Health Issues Are More Common in Women

Contact us at letters@time.com