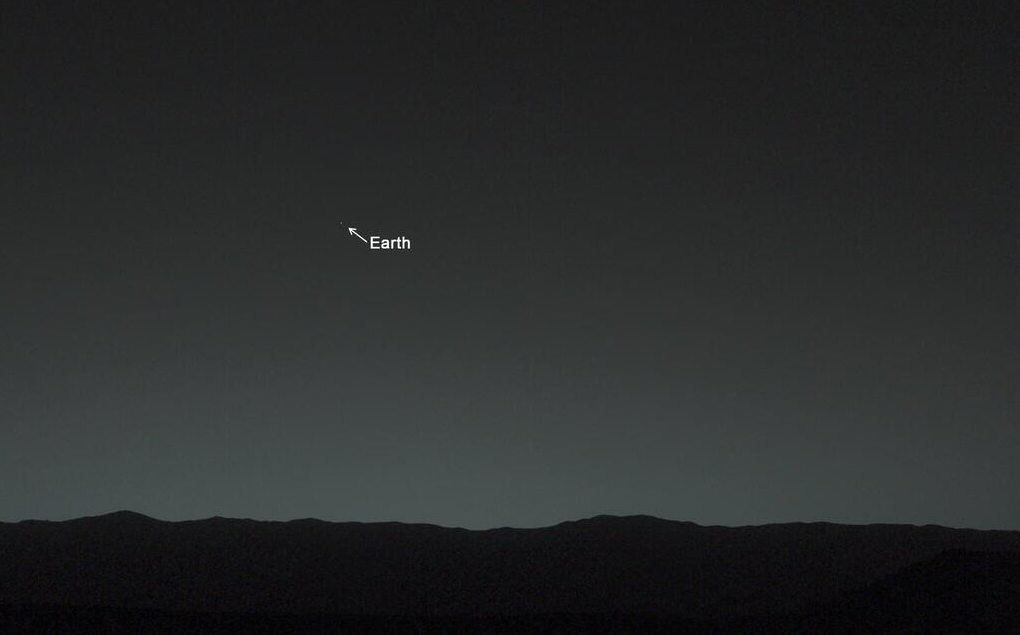

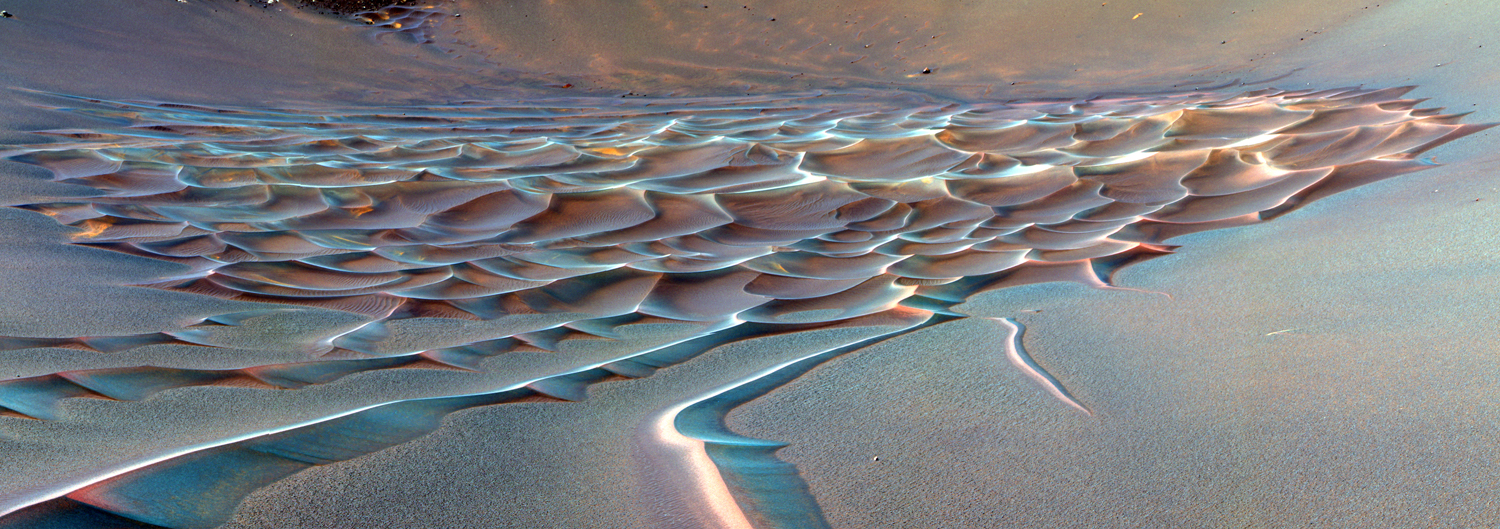

Mars may be the solar system’s most tragic planet. It once had a dense atmosphere; it once fairly sloshed with water; just one of its oceans may have covered two-thirds of its northern hemisphere. With seasons very much like Earth’s, it could have been home to who knows what kinds of life.

But Mars suffered an apocalypse that’s never quite been explained; perhaps meteorite bombardments blasted its atmosphere into space, and the planet’s weak gravity frittered away the rest. The result either way is the cold, dead, dry world we see today. Except now, it seems, it’s not so dry—and perhaps not so dead.

According to a paper just published in Nature Geoscience, there appears to be liquid water flowing on the contemporary Mars. And in this case, it’s not the geological definition of contemporary, which can mean the past few million years, but the common definition, which can mean, say, Tuesday.

MORE: Why Humanity Keeps Putting Off the Trip to Mars

“Mars is not the dry, arid planet planet we thought of in the past,” said Jim Green, director of NASA’s planetary science division, at a packed press conference Monday morning. “Under certain circumstances, liquid water has been found on Mars.”

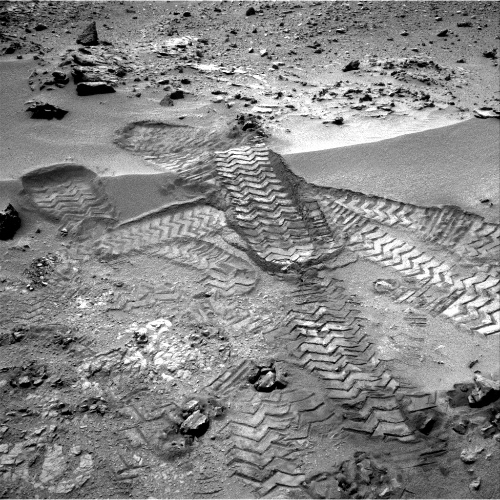

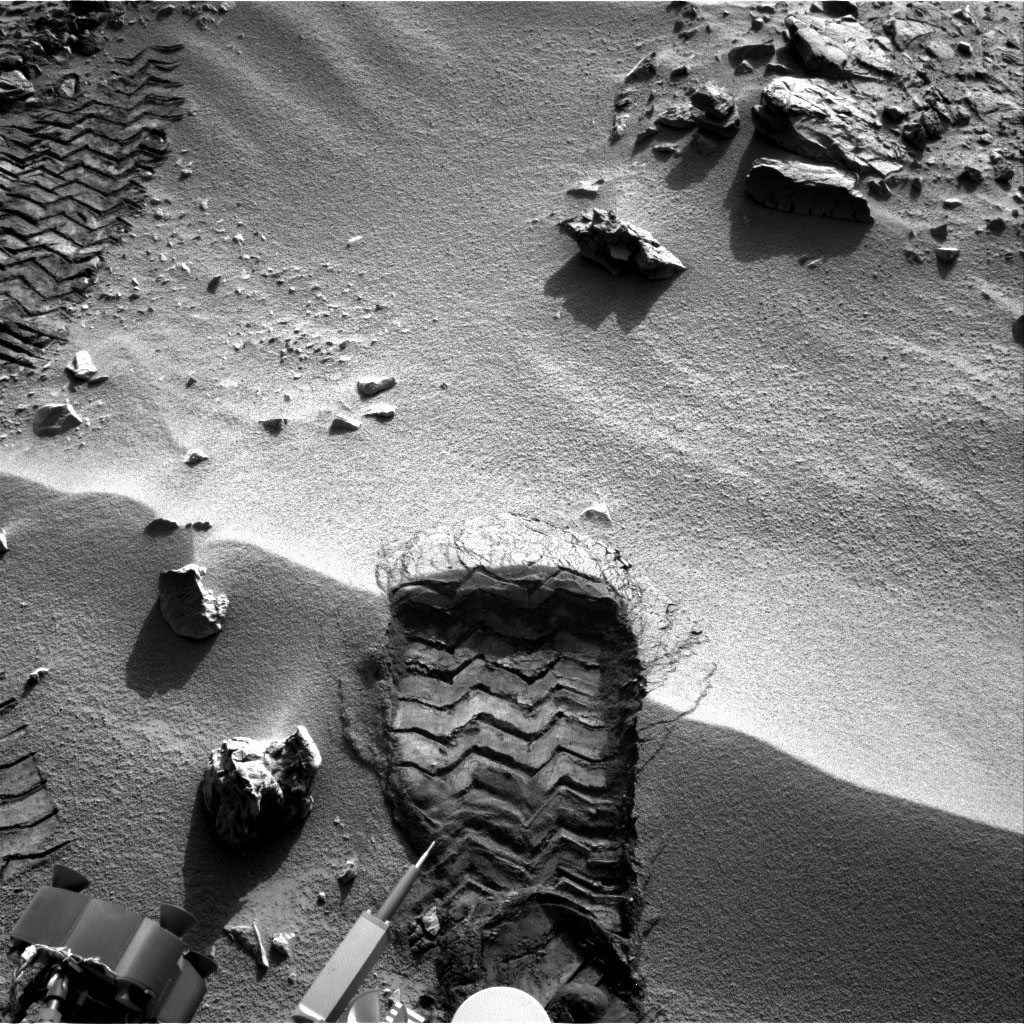

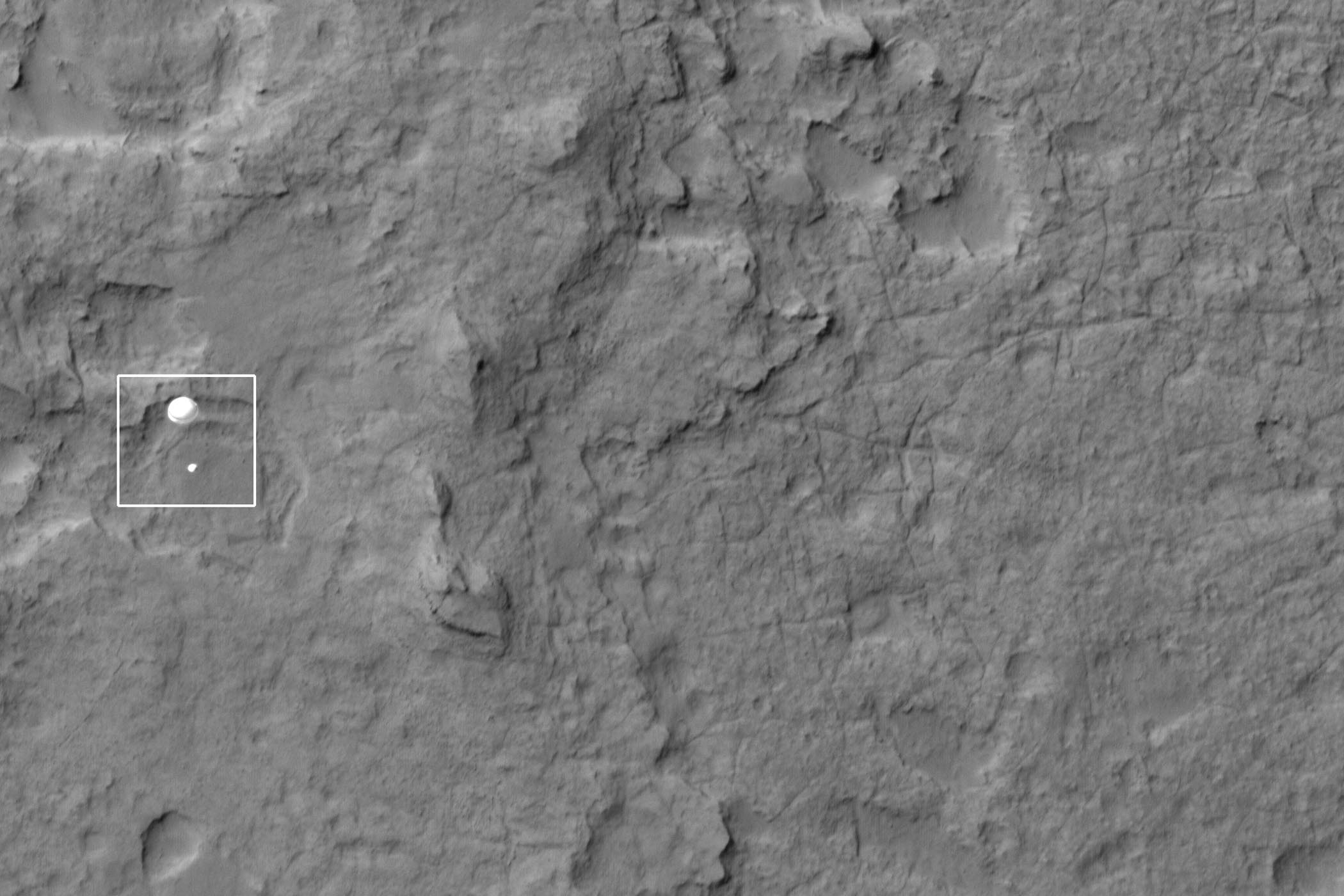

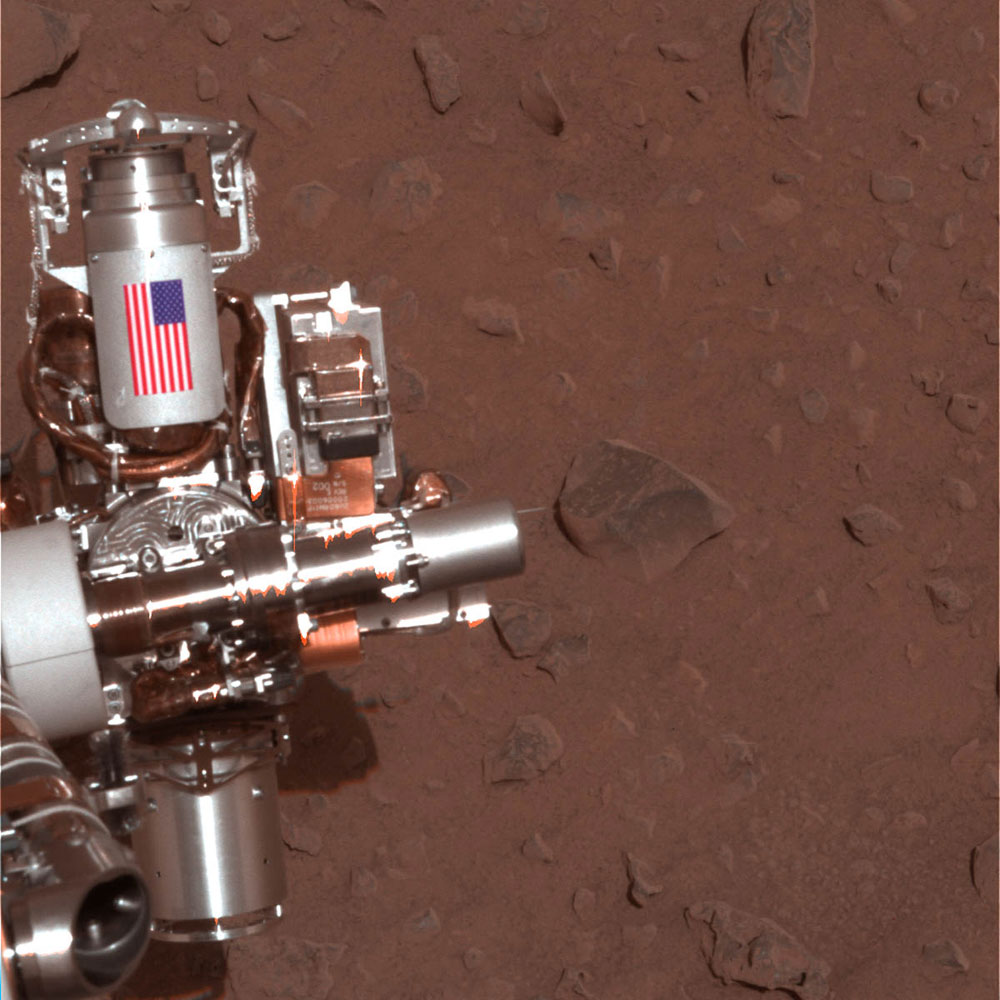

Monday’s announcement goes back to a discovery that was first made in 2010, when then University of Arizona undergraduate student Lujendra Ojha was studying images from NASA’s Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO), and found transitory streaks along the sides of hills and cliffs that looked for all the world like the tracks of running water. The formations appeared in the Martian spring and summer, when water would be the likeliest to exist in liquid form, and disappeared in fall and winter.

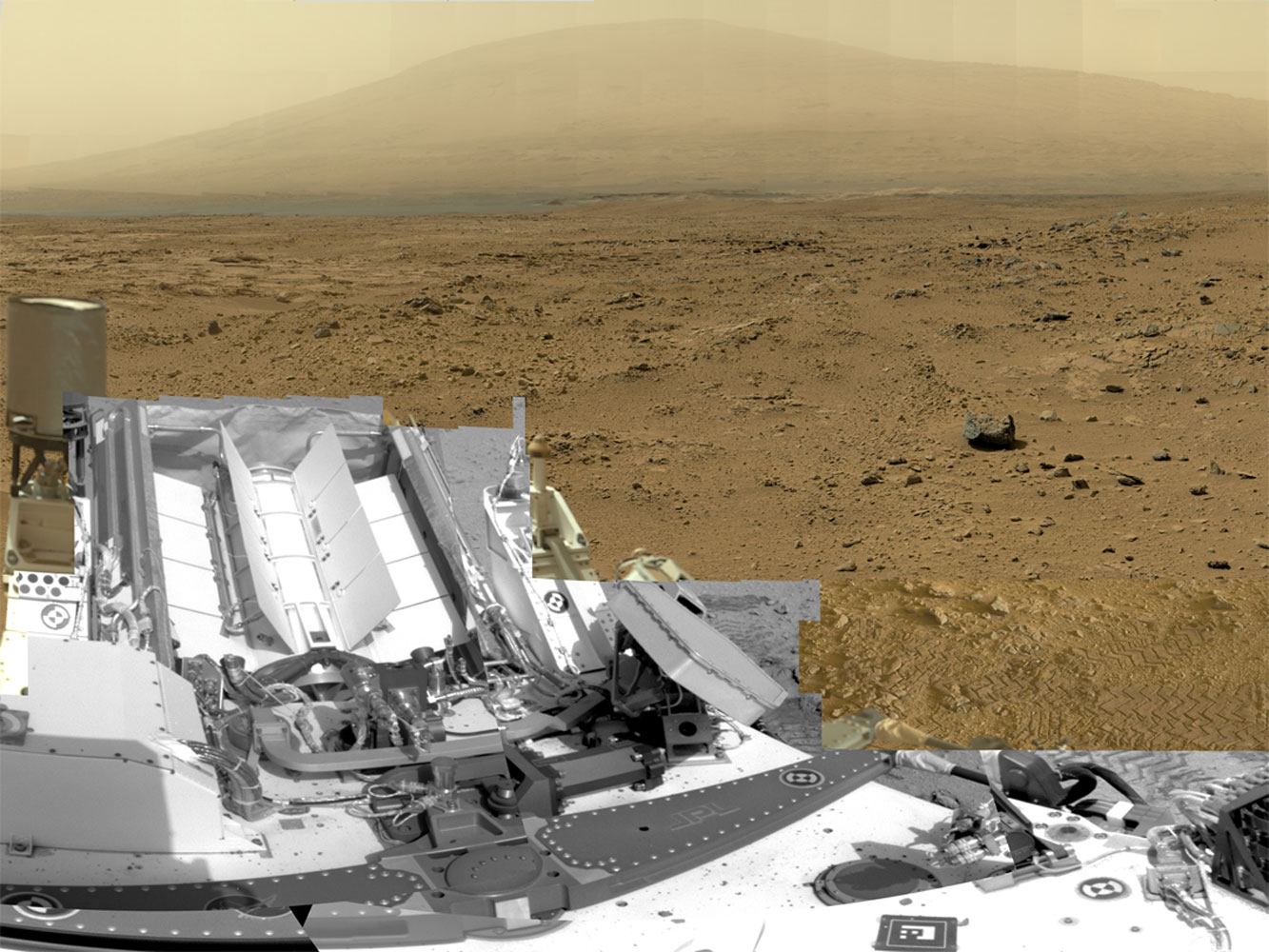

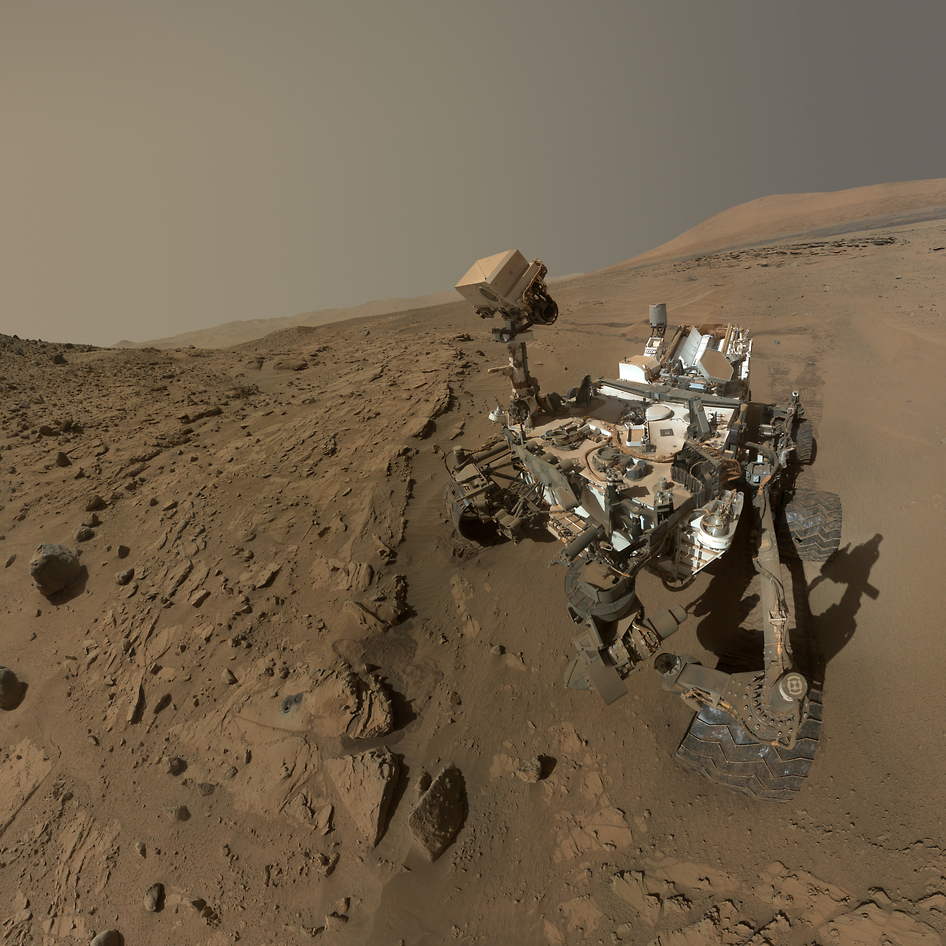

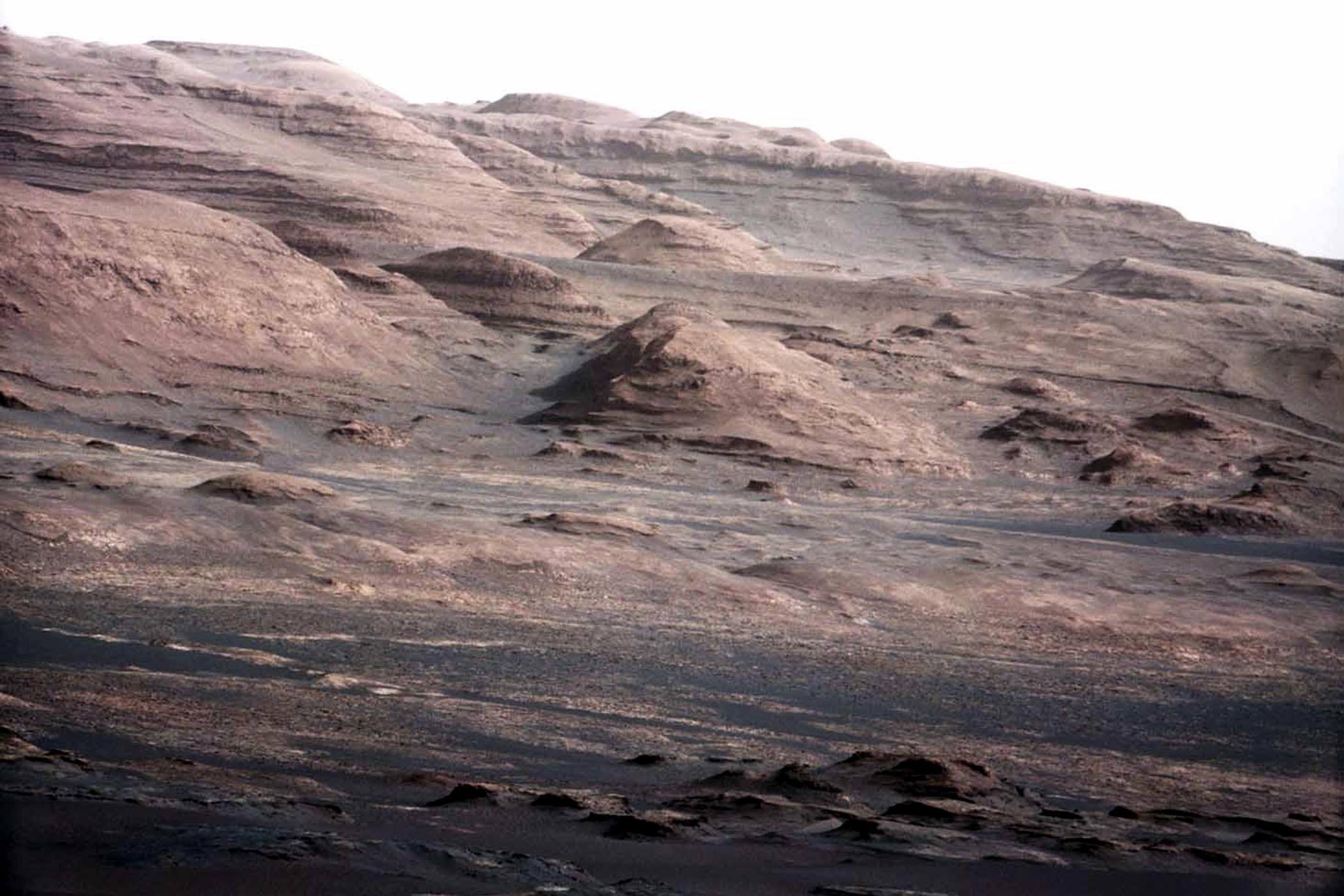

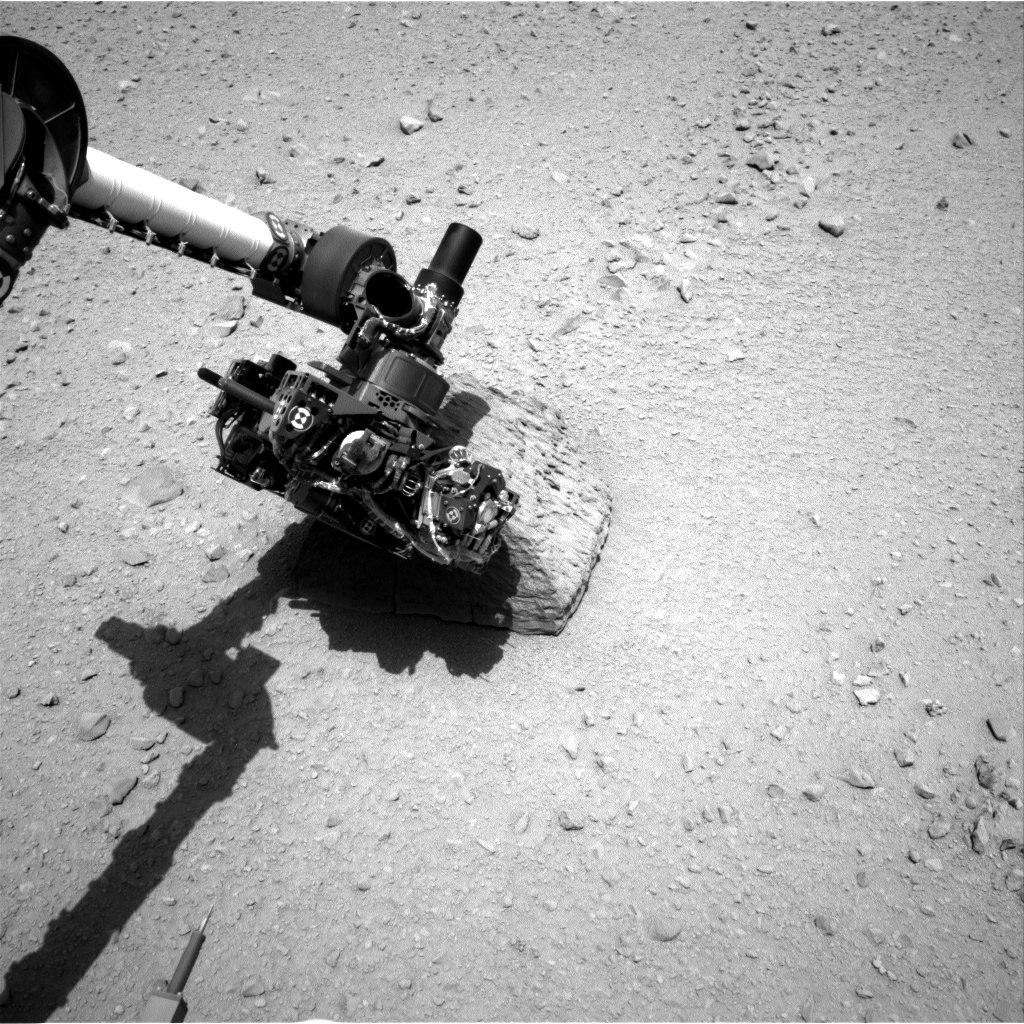

Photos from the Curiosity Rover’s First 2 Incredible Years on Mars

“During the summer months,” says Ojha, “one of the peaks can contain hundreds of narrow streaks.” While it would be tempting to call the markings what they appeared to be—which is to say water—science needs chemical, not just visual, confirmation to make such a call. As a result, Ojha dubbed the streaks “recurring slope lineae” (RSL). “The key evidence that was missing…was their chemical identity,” he says.

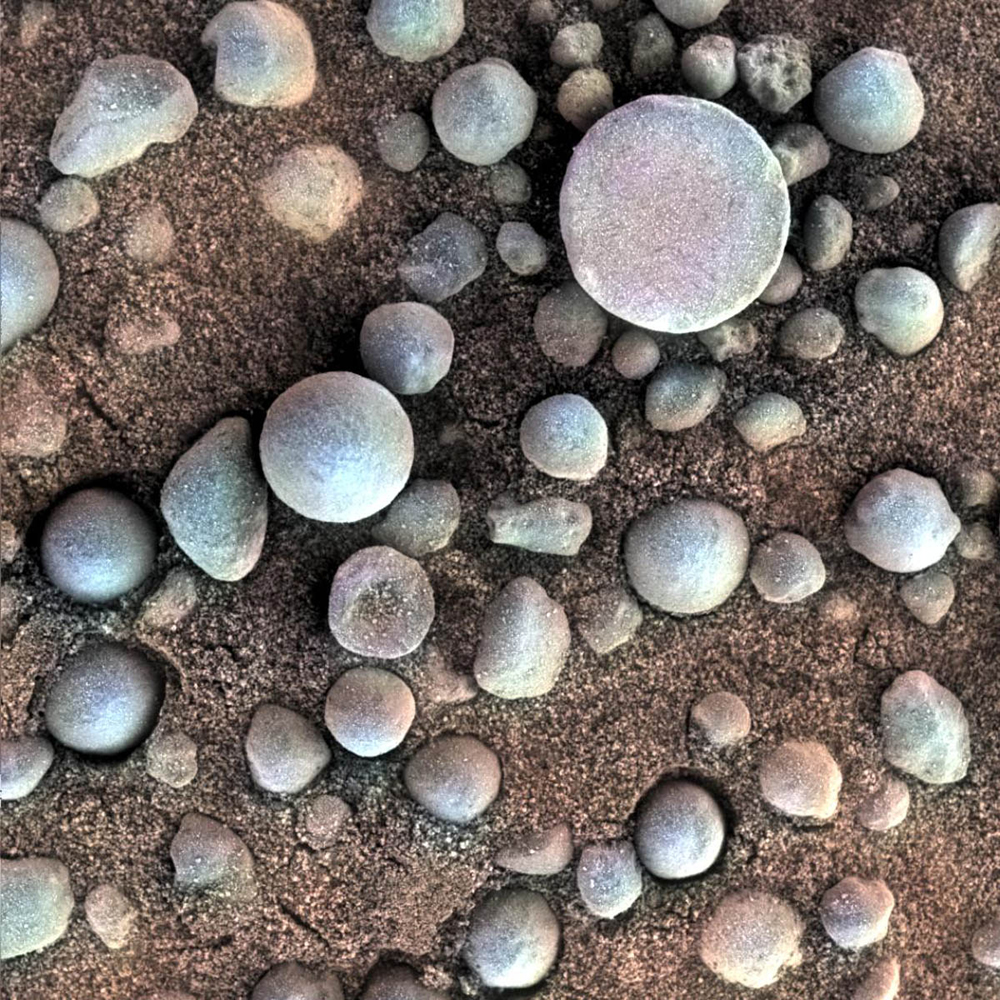

But not anymore. What the Nature paper detailed and the NASA scientists explained were ongoing spectroscopic studies by the MRO that found abundant signs of what are known as perchlorates—or hydrated salts—wherever the RSL are found. It’s the hydrated part of that formulation that’s the key. Given Mars’ extremely thin atmosphere—only about 1% of Earth’s—a glass of water would begin to boil at temperatures as low as 50°F (10°C). But water that’s bound up in the salts stays around.

MORE: A Brief History of the Search for Water on Mars

And in the same way that road salts on Earth lower the freezing point of water so it stays liquid longer, perchlorates on Mars can keep water flowing in temperatures as low as -94°F (-70°C). The durability of the surface water impressed even the scientists who have grown accustomed to being surprised by Mars.

“The MRO observes Mars every day around 3 pm, which is the driest part of the day,” said Ojha, who is now with the Georgia Institute of Technology. “But the water in the molecular structure of the salt would be present still. That fact, he added for emphasis, “means that these features are formed in contemporary water.”

The exact mechanism that causes the water to collect and flow is uncertain. The less-exciting option is that the perchlorates absorb humidity out of the atmosphere, concentrating it until it pools and trickles. The more evocative option is a system of aquifers beneath the Martian surface, which freeze and thaw seasonally.

That second scenario is appealing for more than its familiar, Earthly nature. If organisms of any kind were going to develop in the liquid water, they’d have a better chance of surviving in stable, underground reservoirs than in more transient surface condensation. But even if that’s the case, it’s way too early to conclude that there are microbial Martians at large.

“The potential habitability of Earth-like microbes is unclear,” said Mary Beth Williams of Georgia Tech and NASA’s Ames Research Center. “We need to determine the temperature of the perchlorates.”

Either way, the new discovery helps make a case that NASA has been arguing more and more of late: that the time has come to make the commitment to sending astronauts to Mars. The new discovery offers practical reasons of course: the presence of water on the surface means that there would be less that would have to be imported from Earth for the astronauts to use. And it’s far easier for on-site humans to do the biological studies to look for life in the briny water than it is for remote-controlled machines.

But there are other, more evocative reasons too. Mars, long thought killed in the cradle, might have a richness and potential we never knew. It would be awfully nice to go explore that promise.

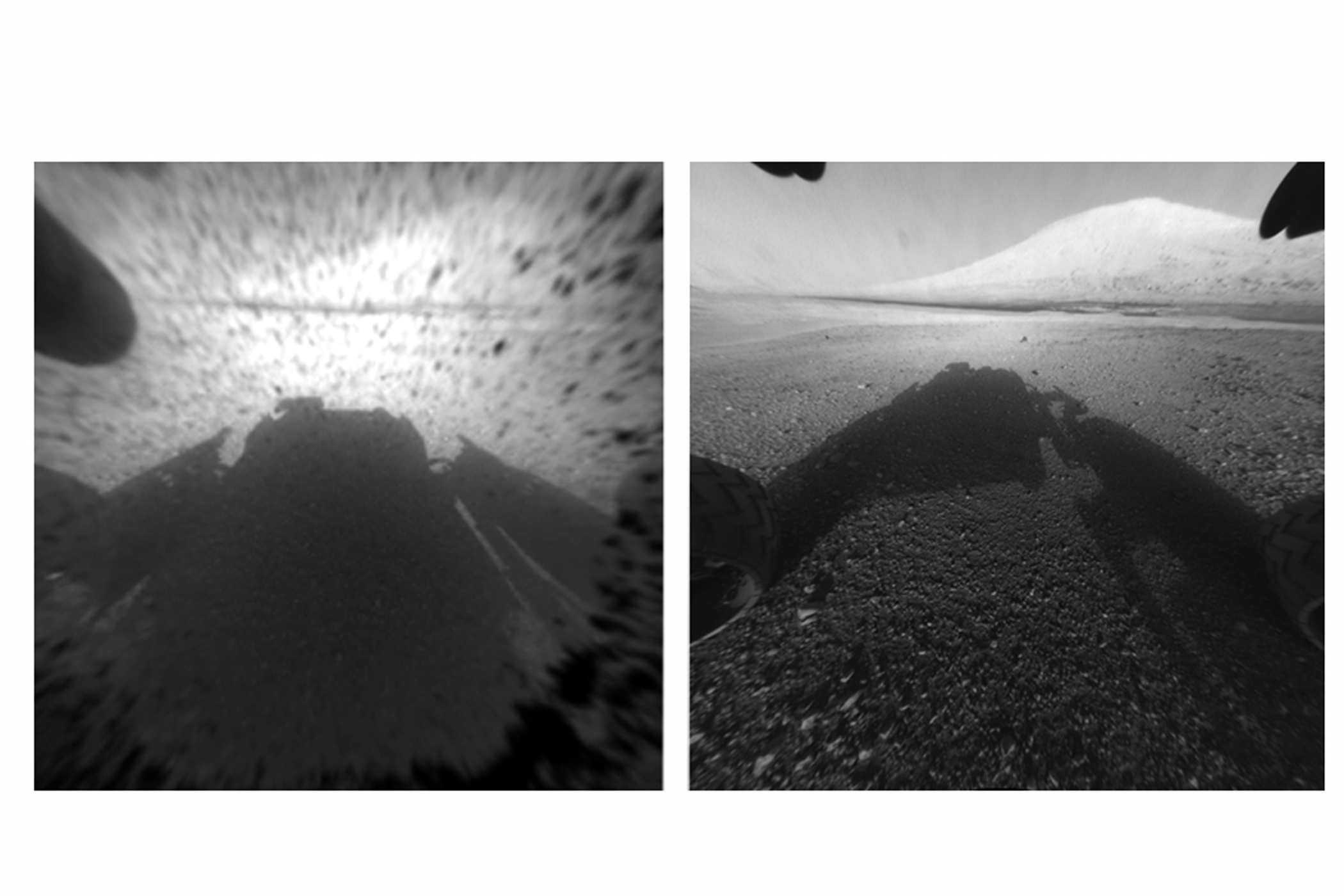

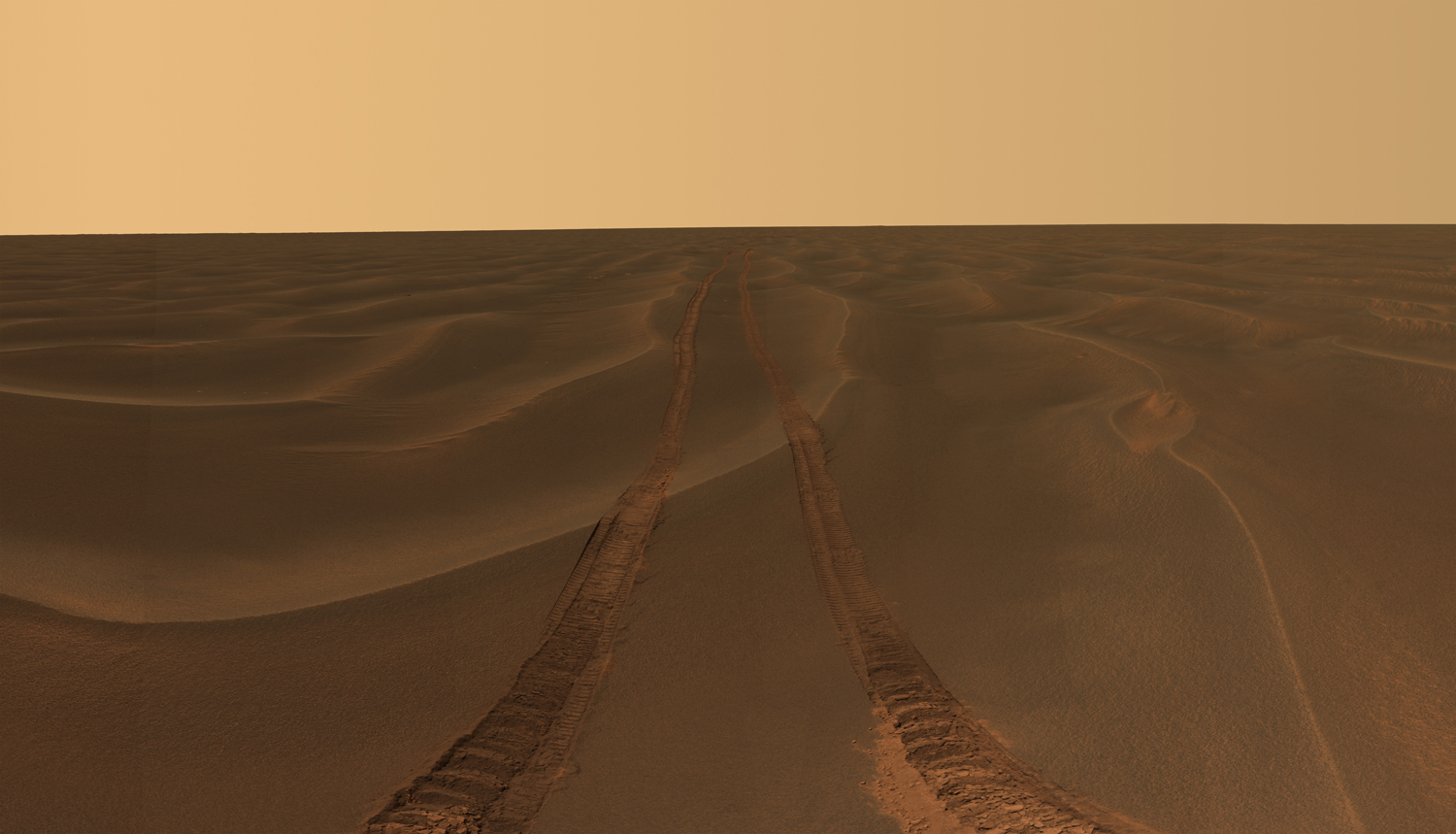

PHOTOS: The Most Beautiful Panoramas and Mosaics From Opportunity’s Decade on Mars

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Trump’s Message Worked on Latino Men

- What Trump’s Win Could Mean for Housing

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Sleep Doctors Share the 1 Tip That’s Changed Their Lives

- Column: Let’s Bring Back Romance

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Jeffrey Kluger at jeffrey.kluger@time.com