For the past 10 days, the trains rolling into Munich’s vast central station have been met by altogether different scenes from the ones that captured the world’s attention earlier this month. Gone are the thousands of migrants and refugees arriving on trains from Austria after a desperate journey of thousands of miles, grateful to finally reach sanctuary. Instead men and women from all over the world, decked out in traditional Bavarian costume, are descending from the trains. Handwritten signs in English and Arabic are still taped to the walls—Welcome to Munich, Welcome to Germany—but the crowds of cheering volunteers who once held them have dissipated. A sugar-sweet aroma fills the air from vendors selling gingerbread hearts iced with messages in the Bavarian dialect: Grüße vom Oktoberfest. Greetings from Oktoberfest.

For two weeks every year, Munich’s picture-postcard streets bustle with tourists and locals in dirndls and lederhosen, descending on the Theresienwiese fairground just south of the railway station to pay homage to the German culture of beer-drinking. (Which involves drinking a lot of it—in 2011, a record 7.9 million liters of beer were served, enough to fill more than three Olympic-sized swimming pools.) Some six million people attend Oktoberfest in the southern German city every year, where it has been held annually since 1810—barring times of cholera epidemic or war. The festivities now contribute more than $1.1 billion a year to the local economy.

In 2015, however, the city’s fabled celebration has coincided with an enormous humanitarian crisis: the influx of tens of thousands of migrants and refugees fleeing persecution, war and poverty in Syria, Afghanistan, Eritrea and elsewhere. From late August onwards, the number of arrivals exploded, partly spurred by German Chancellor Angela Merkel’s statement that the country expects to take in some 800,000 refugees this year. On Sept.12 alone, more than 12,000 migrants disembarked at the Munich terminus, after enduring long, arduous journeys across the continent and tense standoffs with police in Hungary, before finally reaching the southern state of Bavaria.

While volunteers met the refugees with applause and donations, local politicians attacked Merkel’s decision to let in the thousands of migrants stranded in Hungary. Bavaria is one of the country’s most conservative regions, dominated by the Christian Social Union. State premier Horst Seehofer called Merkel’s move “a mistake that we will be dealing with for a long time” and raised concerns over public security during the city’s annual beer festival.

Bavarian Interior Minister Joachim Herrmann also warned of a potential culture clash between crowds of drunken people from Oktoberfest and refugees from the war-torn Middle East—though it wasn’t exactly clear who would pose more of a danger to the other. “Refugees from Muslim countries may not be used to seeing extremely drunk people in public,” he said. “It might seem a bit odd to some of them.”

Though some criticized the state government’s position on social media through the hashtag #Oktoberfestung (October Fortresss), the political pressure from Bavaria may have contributed to Germany’s decision to impose emergency border controls on Sept. 13. The ad hoc measures cut off rail traffic from Austria, introduced spot checks on cars and allowed only E.U. citizens and others with valid papers to pass through. Germany’s decision to effectively exit the Schengen system – which allows passport-free travel across 26 E.U. member states – was widely seen as a sign that Germany was growing weary of shouldering more than its share of the burden in the refugee crisis.

It also sparked fears among refugees that the country that had promised to welcome them with open arms was now turning away. “A lot of people trusted that Germany would help and accept them,” says Colin Turner, a 35-year-old Münchner who has been volunteering at Munich’s train station since the end of August. “That trust has been shaken.”

The introduction of border controls means that Munich is no longer on the front line of the crisis: on Sept.22 German rail operator Deutsche Bahn announced the suspension of key services between Munich and the cities of Salzburg in Austria and Budapest in Hungary. The government has started registered asylum-seekers at the border itself, before sending them off to different parts of Germany according to a quota system that distributes migrants according to each state’s population and economy.

Now, only between 80 and 200 migrants are arriving at the station every day, the same number that Munich had typically seen on a daily basis over the past year. Most have already registered and are in transit to different parts of Germany. Some have been sent to Munich for good; others have been caught walking across the border and put on trains to Munich, and a minority have come from different European countries. They are funnelled through a different exit in the train station, where they can collect food supplies and undergo medical checks before heading to refugee camps—either in Munich or in other parts of Bavaria.

Turner says the border measures have made his work in Munich more complicated. The earlier system was more flexible for refugees, he says, since people could get some water and food supplies in Munich and have a rest before deciding if they wanted to register in Munich or carry on their journey. The new system means that this initial reception period is likely to be more uncomfortable, as refugees have to wait in holding areas at the border for fingerprinting and medical checks before being put on buses or trains to other parts of Germany – a confusing process for many. Smaller towns like Freilassing, near the border with Austria, have also had to mobilize police to deal with an influx of people crossing the border on foot. Whereas Munich locals rushed to help during the crisis, small Bavarian towns are far less likely to have the same amount of manpower and capacity to support refugees seeking shelter after difficult journeys, resulting in more logistical confusion.

Turner says a big city like Munich has the capacity to handle both the refugee influx and the Oktoberfest tourists at the same time. “Even on the highest Saturday we managed to offer a bed or something similar to anyone who stayed here overnight and wanted one. It was intense but it was manageable, ” he says. “The conditions in the smaller towns are not so good. It’s better for the refugees to come here.”

Federal police spokesman Simon Hegewald says dealing with a heavy stream of incoming migrants as well as the annual influx of Oktoberfest revellers would have been extremely challenging. “It’s not that the two groups would fight, but for us, it’s a mass transport problem,” he tells TIME. During Oktoberfest, an additional 100,000 passengers arrive at Munich station every day, on top of the usual 400,000. “It might be manageable but we would need a lot more police officers,” Hegewald adds.

Turner refers to the current lull as “standby mode” – only a handful of volunteers are on duty at any given time, down from a peak of 1,000 helpers during a 24-hour-period at the peak of the crisis. He and other volunteers hope Munich will be reopened as a transit town after Oktoberfest, and that Germany can also find additional transit points around the country for the migrants.

Others agree with German officials that the decision to divert trains to small towns during Oktoberfest was the only real solution. Margit Merkle, 44, has been working with the Munich Refugee Council since 2011, taking care of pregnant women living at Bayernkaserne, a former military base that now houses over 1,000 refugees. “Munich managed for a long time, but now we need this two week break before it becomes a main arrival point again,” she says.

Yet it’s unclear if that will actually happen in the near future. Hegewald tells TIME on Monday that border controls are to remain until November, which means that the situation is unlikely to change even after Oktoberfest ends on Oct.4. For now though, attitudes towards refugees in Munich remain largely positive. “It amazes me, the number of people we have emailing us every day just asking if they can help in some way,” says Merkle. “It’s a rare time I can say I’m proud to be German.”

It’s a pride that many refugees are also keen to share. John Ifeanyi, a 23-year-old Nigerian, arrived in Munich three months ago, after fleeing Boko Haram’s campaign of terror back home. His asylum case is ongoing. Ifeanyi spends his days welcoming fellow refugees at an asylum arrival center, handing out linen and helping newcomers settle in.

“It’s the only way I can help. I love this country,” he says, rolling up his sleeves to reveal thin, shiny scars on his upper arms—souvenirs he says of the time spent in a Libyan prison earlier this year.

“I just want to say thank you to Germany for changing my life, for bringing me back from the dead,” he says. And while the Oktoberfest celebrations continue, trains are still rolling into Munich station, delivering more people like Ifeanyi— filled with hope that Germany will do the same for them.

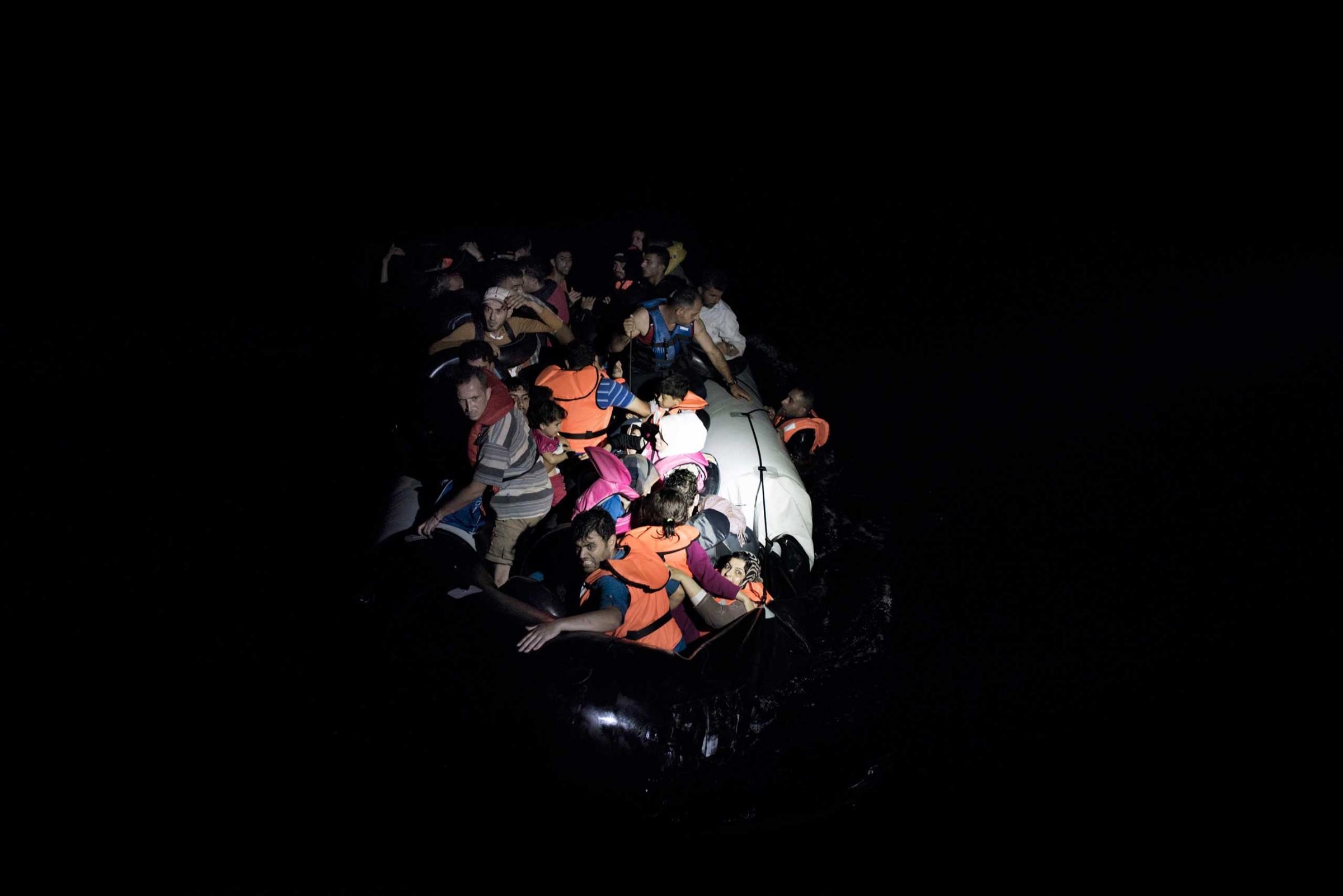

These Photos Show the Massive Scale of Europe’s Migrant Crisis

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Where Trump 2.0 Will Differ From 1.0

- How Elon Musk Became a Kingmaker

- The Power—And Limits—of Peer Support

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Naina Bajekal / Munich at naina.bajekal@time.com