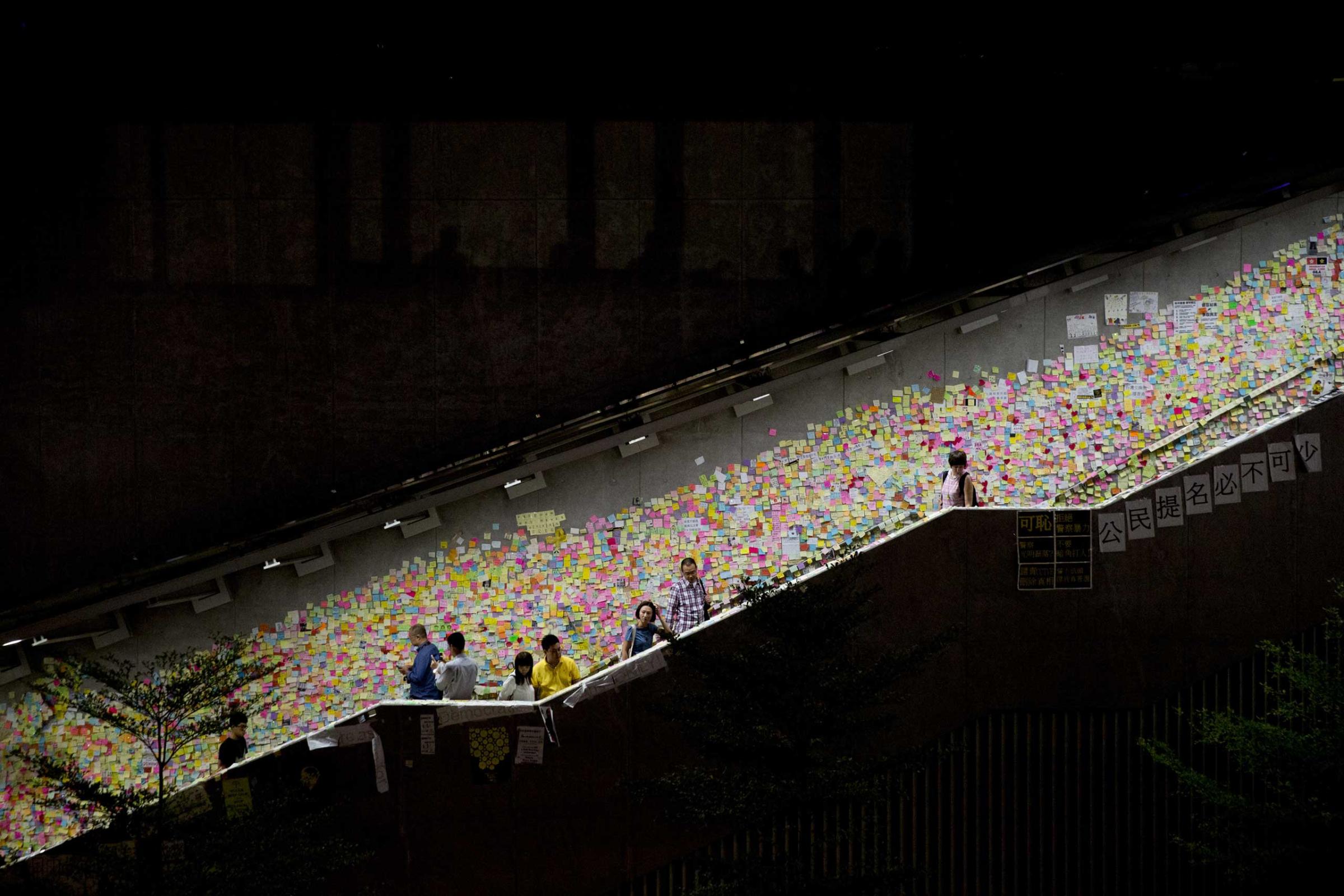

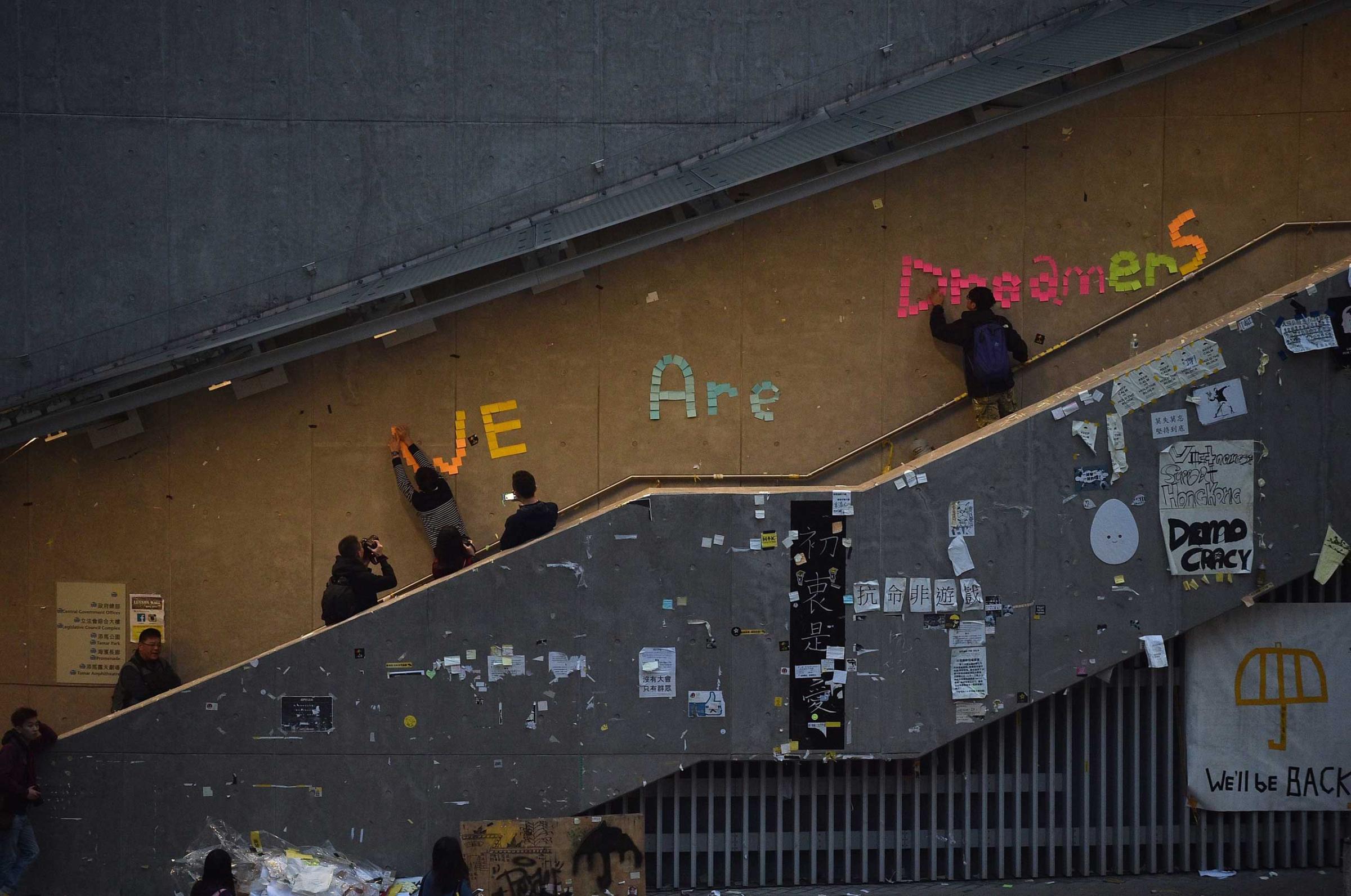

Hong Kong’s Umbrella Revolution — the 79-day pro-democracy protest that began on Sept. 28 last year — not only brought tens of thousands onto the streets. It also witnessed an outpouring of creativity.

At night, the tent villages set up by protesters in key city districts were alive to the sounds of philosophical debates and strummed guitars. Artists created elaborate sculptures and set up large canvases to paint the historic scenes as they happened. Schoolgirls made brooches in the shape of the movement’s symbol — umbrellas, so adopted because protesters used them to shield themselves from police pepper spray — while others chalked flowers on the pavement.

In an echo of the 1968 Paris uprisings, a large sign in French, erected over the main protest area in the Admiralty district, read: “Sous les pavés, la plage!” (“Under the paving stones, the beach”).

But, a year later, the city is at a crossroads, with some artists inspired by the passion of Occupy Hong Kong, as the protests are also known, while others worry this new openness will beget a collision course with China, the city’s intransigent sovereign power. What is clear, however, is the shared feeling that new cultural realities exist.

“Hong Kong is like a baby waking up,” Kacey Wong, a 45-year-old visual artist, tells TIME.

After spending many days among the protesters, Wong was struck by how personal Hong Kong’s politics had become. “Everyone talked about politics, even though few had been engaged politically before this,” he says. In the spring, Wong exhibited his Occupy-inspired art at Amelia Johnson Contemporary, a top gallery in Hong Kong. This fall, he will be exhibiting related work in Paris. “Occupy brought politics into the home, separating families, and causing fragmentation between the young and old,” he recalls.

That fragmentation inspired literary art as well as visual. “Occupy saw a real outpouring of expressive writing in a way that has not happened in Hong Kong,” says Elaine Ho, professor of English at Hong Kong University. In recent years, she says she’s noticed interest in creative writing in English has also increased. “As with most very young writers, the first work is often autobiographical, talking about themselves and about issues of identity. I think there is also a fairly significant attempt to engage with the world outside of themselves.”

Denise Ho agrees that there has been a seismic shift. “I think Hong Kong is different now,” says the popular local singer and Umbrella Revolution supporter who took part in demonstrations and street occupations. “Even though we didn’t really change any of the government’s actions or get what we asked for, I think the seed is actually planted in the younger generation who are thinking about how they should live their life.”

Ho was one of a group of musicians who wrote and performed “Raise Your Umbrella,” a song that would become the unofficial anthem of the Occupy Movement. She was arrested by police on Dec. 11 as city officials called for the clearing of the camps, and her participation has had professional consequences.

“My work has done a complete one-eighty,” Ho told TIME earlier this month. Before she went public in support of the students and protesters last year, 80% of her income came from sources in, or with close ties to, mainland China. Today, those sources of income are gone, Ho says. This August, Ho even struggled to find guest acts to accompany her on stage in Hong Kong. Being seen as sympathetic to her politics was cause enough to fear reprisals.

Anthony Wong, another well-known pop performer and Occupy supporter, who, like Ho, appears on “Raise Your Umbrella,” told the South China Morning Post in April of this year that he had received no new jobs since he had aligned students and protesters the previous fall.

“Our [creative] industry has become so dependent on the Chinese market to survive it is affecting the way people are creating music … the themes they would choose or avoid,” Ho says.

Filmmakers are also feeling the crunch.

“When I arrived in the 1980s, [filmmakers] came because there was an energy,” award-winning cinematographer and longtime Hong Kong resident Christopher Doyle tells TIME. “Somewhere along the way Hong Kong forgot that sense of optimism.”

Days earlier, Doyle and his crew celebrated the Hong Kong release of his latest film, Hong Kong Trilogy, which offers viewers a “meditation or reverie” of the city as the viewer tracks three generations of Hong Kongers. Doyle, perhaps best known to international audiences for his stunning work on Wong Kar-wai’s In the Mood for Love, was inspired by the energy of the Umbrella Revolution and a need to bear witness in a place that has given him so much.

“I am sitting here because of Hong Kong,” he tells TIME, while sipping a beer. Describing the role the democracy movement and street occupations play in the film, Doyle says: “Being together, sharing ideas, sharing a space that you’ve never had because its too expensive to live together anywhere in Hong Kong now, that’s what it was about.”

Some viewers will inevitably parse politics from the film. In the final scene, music and lyrics, sung in Cantonese over the sound of crashing waves, offer a closing stanza: “We can no longer stand idly by.”

“I’ve accepted that I might never work in China again” because of the political message of the movie, Doyle tells TIME. “We just have to that trust in the process, trust in filmmaking as a conduit or bridge, and finally have the courage to say: ‘Throw me in jail for the best reasons.’”

If we don’t speak now, he says, “we’ll be Tibet.”

79 Days That Shook Hong Kong

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com