“It was frightening, mostly, in retrospect,” says photographer and artist Matthew Connors when looking back at his time in Egypt, two years after the revolution that toppled President Hosni Mubarak. “When I was there I was shockingly naive to the level of danger.”

Connors’ first book Fire in Cairo is a record of that first impression and presents an array of dislocated images – laser beams, shadows, smoke and fire – that build a disorienting album of a country in turmoil. He photographed all the work during a series of trips from January 2013 till the military coup that ousted Mubarak’s successor, President Mohamed Morsi. It was six months when many Egyptians had grown weary of the seemingly endless tumult in the streets and the high-handed rule of Morsi’s Muslim Brotherhood government.

The book is intentionally designed with no clear place to start: it invites the readers to begin from the front or the back. Connors presents images with no captions. In fact, the only text offered is laid out in reverse and is a brief historical fiction written by Connors himself and inspired by postmodernist writer, Donald Barthelme. “Barthelme has short stories where the tone and the swift verbal collage along with the mixture of violence longing and absurdity all resonated with my experience of being in Cairo,” he says. “In some ways I intended to imitate him.”

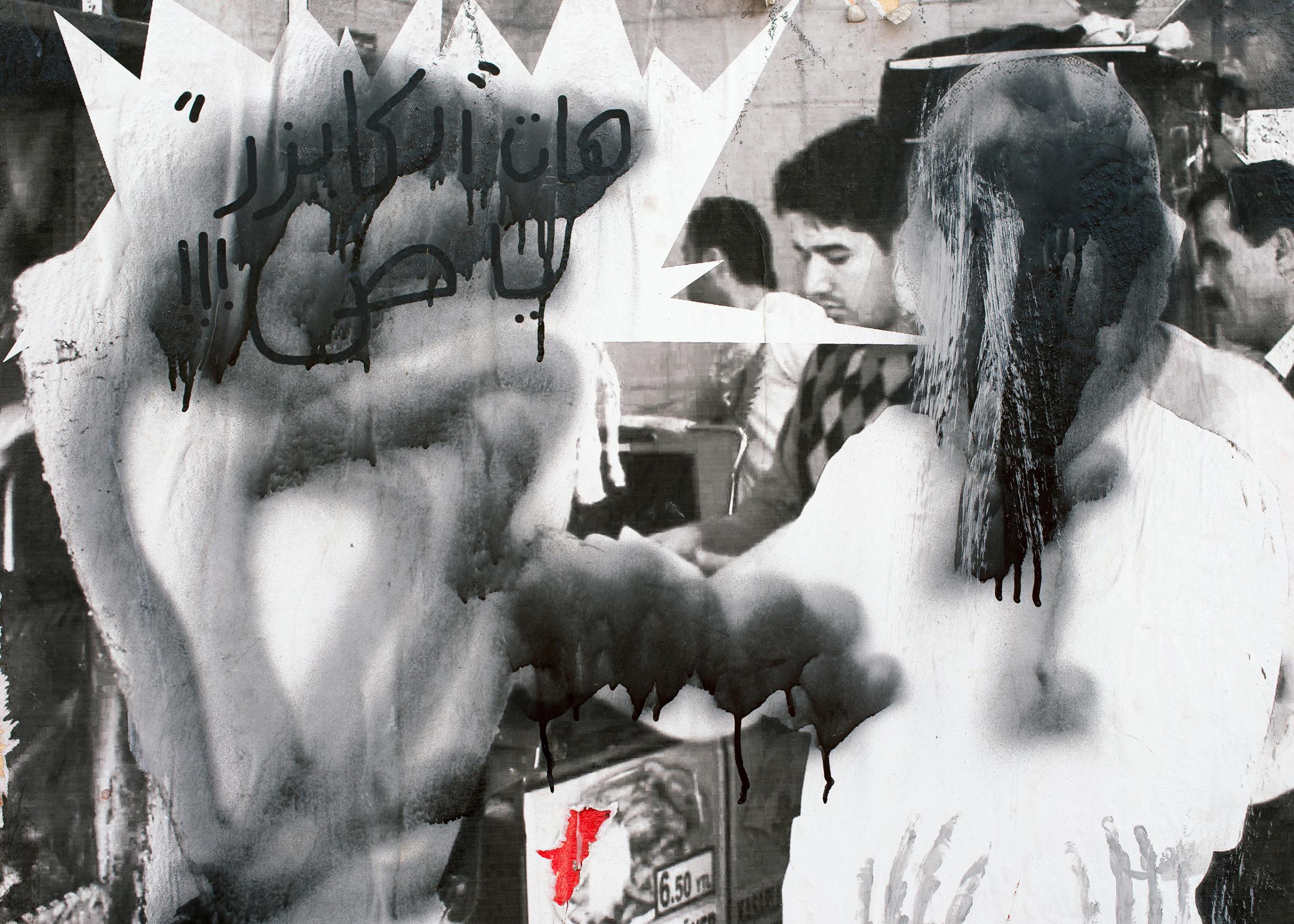

Recalling news images from Egypt during those years may conjure an endless stream of pictures from Tahrir Square with masked protestors caught in clouds of gunfire, tear gas, and barricades. Unlike most photojournalism which attempts to document the kinetic action and the clearest portrayal of the situation, Connors works in the opposite direction, shooting detail after detail of opaque, ominous, and brooding scenes of danger. “For many moments I was literally standing next to journalists and we were photographing the same scenes but oftentimes our cameras would be pointed in very different directions,” he says.

Blood drips from the tire of a BMW in one photo, helicopters seem to fly upside-down in another and smoke screens blur all the action. “It has elements of surrealism and magic realism that go throughout, where the pictures and the short story I wrote and the layout all sort of navigate between reportage, poetry, and surrealism to signal the chaos and confusion going on there,” he says.

Connors’ work in Egypt started back during the Occupy movement, which was a turning point for him as a photographer as he began experimenting with portraiture. In the project General Assembly he photographed over 650 portraits of Occupy protestors and met activists from Egypt who encouraged him to continue his work. On the first visit he says he fell in love with the city. He immersed himself in its history which felt tangible at every turn. “I was trying to find different kinds of visual and literary idioms that could suggest something more palpable about the emotional aspirations of the Egyptians, but also my own take on the situation,” he says.

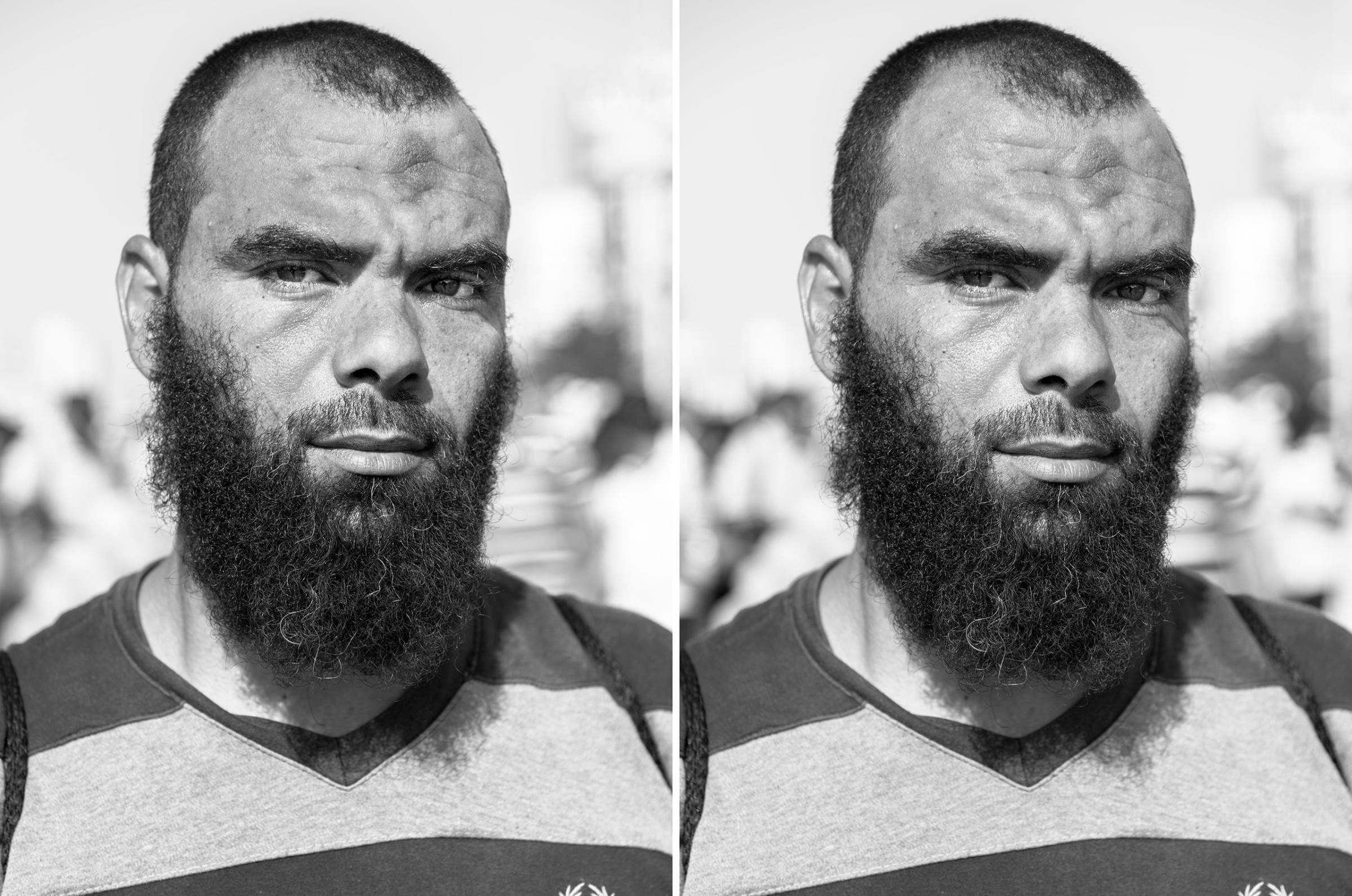

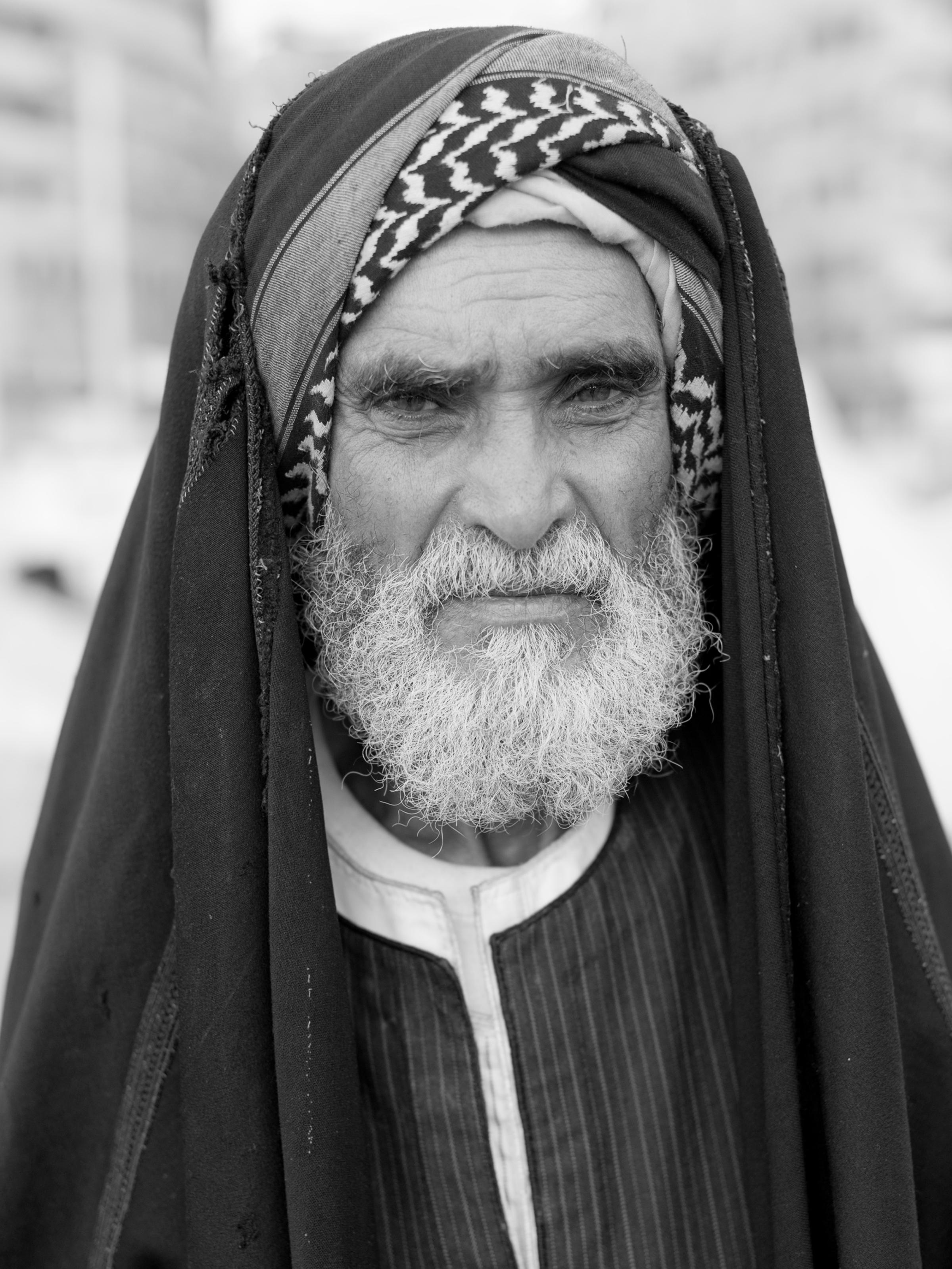

The color images, depending on the direction you navigate the book, begin or conclude with a series of black and white portraits of the protestors and police. The near frames of each diptych portrait feel like stereoscopic images with only the slightest difference between them, grounding the book in its people. “I think it’s a flow that works both ways,” he says of the book’s ambiguous layout. “I wanted this element of confusion and I wanted to mimic my experience of being in Tahrir where the ground was constantly shifting and I really wasn’t sure who was on what side.”

The ambiguity of the images builds a story of a revolution lost along with the extreme emotions of the time – emotions that were stifled and now exist in a state of limbo.

“I think the book is something that, as a genre, I would consider to be more historical fiction,” he says. “I would want people to have the experience that I have when I read a really immersive incredible novel. [One that] is linked to a particular moment in history so that the story and the narrative reverberates through their understanding of what is possible in the world and what can happen.”

Matthew Connors is a photographer, professor and the photography at department chair Massachusetts College of Art & Design in Boston.

The book published by SPBH Editions, edited and published by Bruno Ceschel, and designed by Antonio de Luca has been shortlisted for the Paris Photo-Aperture Foundation PhotoBook Awards in the First PhotoBook category.

Paul Moakley is the Deputy Director of Photography at TIME and you can follow him on Twitter here.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com