ISTANBUL: Jaafar Moustafa and Hasan Salem are counting down the days until they can board a plane in Istanbul, each with a one-way ticket to Oakland, California, and escape from the trauma and tragedy of their native Syria.

Moustafa, 26, and Salem, 30, are part of a very select group. They are among the 18,336 Syrian refugees whom the United Nations has recommended for resettlement in America since the Syrian civil war began in 2011. Compared to the more than four million people who have escaped Syria, that number seems tiny—and it is. But most of the refugees the U.S. will try to take in for resettlement have extremely dire medical needs or can never return home because they will almost certainty face political, religious or social persecution.

For Moustafa and Salem, returning to Syria would be suicide. The two friends left the port city of Latakia, Syria on May 10, 2014. It’s a date they will never forget. The city they ran from remains under the grip of Syrian President Bashar Assad, whose war with an array of rebel groups has killed over 200,000 Syrians and displaced millions more. But neither Assad’s brutality nor the fear of their hometown one day falling under the control ISIS are why these men abruptly fled their home. Both Moustafa and Salem are gay, and they left Latakia because they were outed.

“We could never be out of the closet in Syria,” said Moustafa. “You can’t tell people that you’re gay and live a normal life.”

After relatives found emails between the two about a LGBTI conference in neighboring Turkey, staying in Syria was no longer possible. Moustafa was afraid his uncle would kill him, and Salem feared his own father would murder him. So the two packed what they could and flew to Istanbul together, joining the more than 1.5 million Syrians who have sought refuge in neighboring Turkey.

Moustafa and Salem were lucky—in Istanbul a UN caseworker deemed them highly vulnerable refugees. Because they are at such high risk of becoming victims of a hate crime, they fall into the category of refugees most in danger and best suited for resettlement. When refugees like Salem and Moustafa face having their fundamental human rights violated, resettlement becomes the most appropriate solution, according to UN regulations.

Salem and Moustafa’s caseworker determined that America would be the safest place for them. When they left Syria, they had no connection to California. To this day, they have no clue why the UN recommended they be resettled in the U.S. and not somewhere in Europe, though family ties and language skills are factors when finding refugees a new home. While Moustafa and Salem have no relatives in America, they both speak some English. Their basic English skills could now be why their potentially lethal “outing,” has become a blessing in disguise.

“I feel very lucky, of course,” said Salem. In California, “society will accept me.”

But while these two no longer have to live in fear of their families brutally attacking them, they are leaving the only home they’ve ever known for a new life in a foreign country.

Peter Vogelaar, head of Affiliated Services at the International Catholic Migration Committee, says refugees like Salem and Moustafa who ICMC helps resettle in America are told, “streets aren’t paved with gold. There are a lot of challenges. Making ends meet is going to be very hard to do.”

Once the UN recommends a refugee in Turkey to be resettled in the U.S., non-profits like ICMC in Istanbul are summoned to provide the asylum seeker everything from a thorough medical exam to a translator for an in-depth interview with the Department of Homeland Security (DHS). The DHS agents are tasked with ensuring the refugee poses no security risk to the U.S. Salem and Moustafa also had to respond to a series of questions designed to confirm they truly would face death at the hands of their relatives if they were to return to Latakia.

When Moustafa and Salem land in California next month, U.S.-based non-profits will help them find work and classes to improve their English. Before they land jobs they’ll be eligible for U.S. federal assistance, like food stamps, but won’t be given a stipend to get started—as refugees are in Europe. The responsibility will ultimately be on them to make their resettlement successful.

Of the 18,336 refugees the UN recommends the U.S. adopt, only about 1,500 of them have already completed the lengthy resettlement process and moved to America. It’s not clear how many of them are LGBTI. “In some countries of asylum, gender identity may make refugees particularly vulnerable and in others it may not,” said Ariane Rummery, a spokeswoman with the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees.

With White House pledging to take in at least 10,000 Syrians this upcoming fiscal year, Moustafa and Salem are part of a pioneering group of refugees. They say they are up to the challenge of adapting to a new country—a prospect that seems significantly less scary after surviving wartime Syria.

The two will arrive in their new country emotionally scarred from experiencing Syria’s civil war. Since their hometown remains under Assad’s control, Latakians were not pounded daily with barrel bombs from the Syrian Air Force. But even so, Moustafa says life in Latakia is, “still miserable.” If you dare to publicly speak out against the relentless regime, “they arrest you immediately,” he says. And the crackling of gunfire they frequently heard reminded them the front was not so far away.

“War, blood, I saw many things,” said Salem.

While Salem hopes to continue his career as a computer technician, Moustafa intends to seek a position in social work once in Oakland. He wants to be an LGBTI activist and help other gay refugees. And above all else, they want the freedom to be “out” in the open.

“It’s a liberal country and you can follow your dreams,” said Moustafa. His American Dream is to fall in love and eventually marry. It is a dream that could never turn into reality in Syria.

“I want to live a normal life. I want to feel safe. I want basic things that everybody should have.”

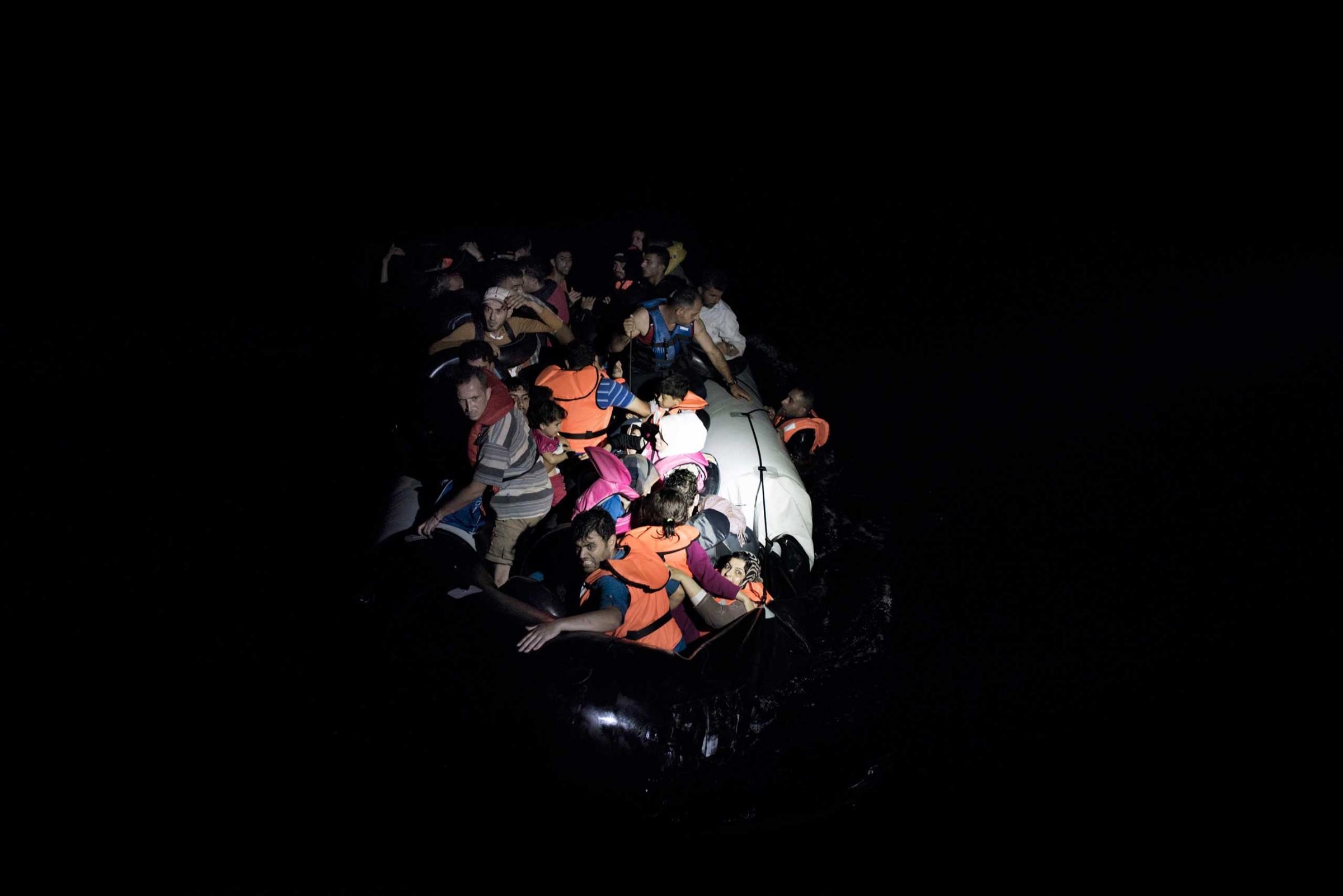

These Photos Show the Massive Scale of Europe’s Migrant Crisis

More Must-Reads from TIME

- How Donald Trump Won

- The Best Inventions of 2024

- Why Sleep Is the Key to Living Longer

- Robert Zemeckis Just Wants to Move You

- How to Break 8 Toxic Communication Habits

- Nicola Coughlan Bet on Herself—And Won

- Why Vinegar Is So Good for You

- Meet TIME's Newest Class of Next Generation Leaders

Contact us at letters@time.com