It should have been easy enough: in September of 1930, as Secretary of the Interior Ray Lyman Wilbur formally initiated construction on a major Colorado River dam, he proclaimed the following: “I have the honor to name this dam after a great engineer, who really started this greatest project of all time—the Hoover Dam!”

Except that, officially, the dam wasn’t actually named for the president. Tradition at the time called for naming a project for the law that made it possible, which meant that America’s most impressive feat of engineering was called the Boulder Dam, after the Boulder Canyon Project Act. Bills to rename it for Hoover failed in both 1929 and 1930. And in 1933, when Hoover left the White House and the Democrat Franklin Roosevelt moved in, the new administration declared that the proper name would be used exclusively.

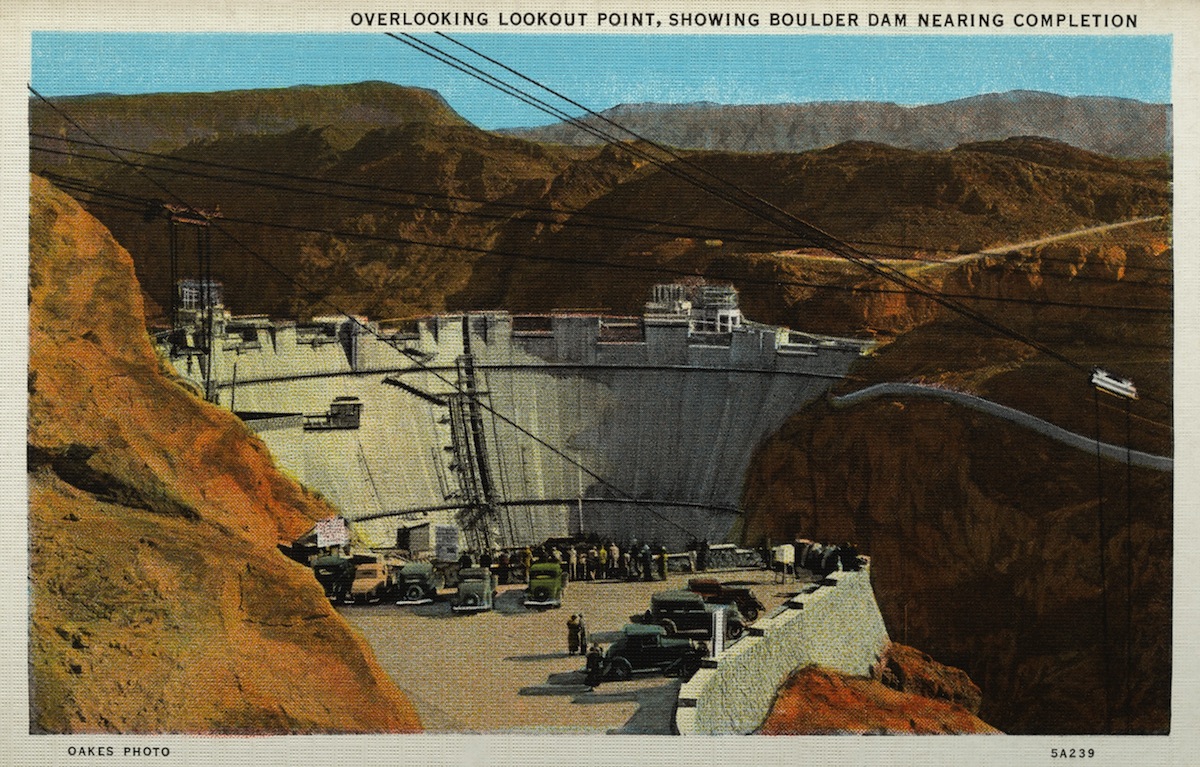

In the years that followed, whether one called the under-construction dam “Hoover” or “Boulder” was often an indication of political party. Sure enough, when President Roosevelt dedicated the nearly completed dam on this day, Sept. 30, in 1935, he was sure to refer to it in his speech as the Boulder Dam. Moreover, Roosevelt used the occasion to advance his own very un-Hoover program of public works. “Obviously, for instance, this great Boulder Dam warrants universal approval because it will prevent floods and flood damage, because it will irrigate thousands of acres of tillable land and because it will generate electricity to run the wheels of many factories and illuminate countless homes,” TIME quoted the president as saying. “But can we say that a five-foot brushwood dam across the head waters of an arroyo, and costing only a millionth part of Boulder Dam, is an undesirable project or a waste of money?”

It would be more than a decade before President Truman broke with his party’s tradition and signed a congressional resolution making “Hoover Dam” official. The namesake president was gifted with one of the ceremonial signing pens.

But, as TIME reported, not everyone was happy: “Merchants, contemplating a quarter of a million dollars’ worth of ash trays, sofa pillows and other knicknacks emblazoned ‘Souvenir of Boulder Dam,’ tried to decide what to do,” the magazine observed. “They could get rid of them at a loss. But what if the next Congress were Democratic?”

Read more about the dedication, from 1935, here in the TIME Vault: Roadwork

More Must-Reads from TIME

- How Donald Trump Won

- The Best Inventions of 2024

- Why Sleep Is the Key to Living Longer

- Robert Zemeckis Just Wants to Move You

- How to Break 8 Toxic Communication Habits

- Nicola Coughlan Bet on Herself—And Won

- Why Vinegar Is So Good for You

- Meet TIME's Newest Class of Next Generation Leaders

Write to Lily Rothman at lily.rothman@time.com