It was a hot late-summer morning, a month into my first year as a Duke medical student. The classroom of nearly 100 students buzzed with energy. After a few weeks of mostly tedious lectures that seemed no different from the science classes we’d taken in college, our professor had just finished the first half of his presentation on the case of a young boy with a rare childhood disease. A short film had brought the complex scientific data in our textbook to life in the words and actions of the boy and his parents. Following the video, the professor talked about promising therapies for this disorder. Finally, we were getting glimpses of the clinical knowledge that we’d come to medical school to learn. I could hardly wait for the second part.

But that wasn’t the only reason that I suddenly felt better. My first few weeks at Duke had been an exercise in expanding insecurity as I learned more about my classmates. As one of a handful of black students, I naturally stood out, but race was just part of the story. In those early days, it seemed that all of my classmates came from professional, well-to-do families. My mom never entered a college lecture hall; my dad did not finish high school. While my brother, Bryan, had been the trailblazer of our immediate family in graduating from college, medical school was a different league. The majority of my classmates graduated from high-prestige colleges like Duke, Harvard, Yale, or Stanford. I’d gone to the University of Maryland–Baltimore County (UMBC), a young school with a limited national profile. Could I hack it at Duke? Determined to use this fear as a buoy rather than a deadweight that could sink me, I probably spent as many hours studying in that first month at Duke as I had my entire senior year of college.

The effort paid off. Our midterm scores had just come back, and, to my immense relief, I had done well, firmly within the top half of the class on each exam. As I stood to stretch during the break before the professor resumed his lecture, I was finally starting to feel comfortable, or at least what qualified as such for a first-year medical student.

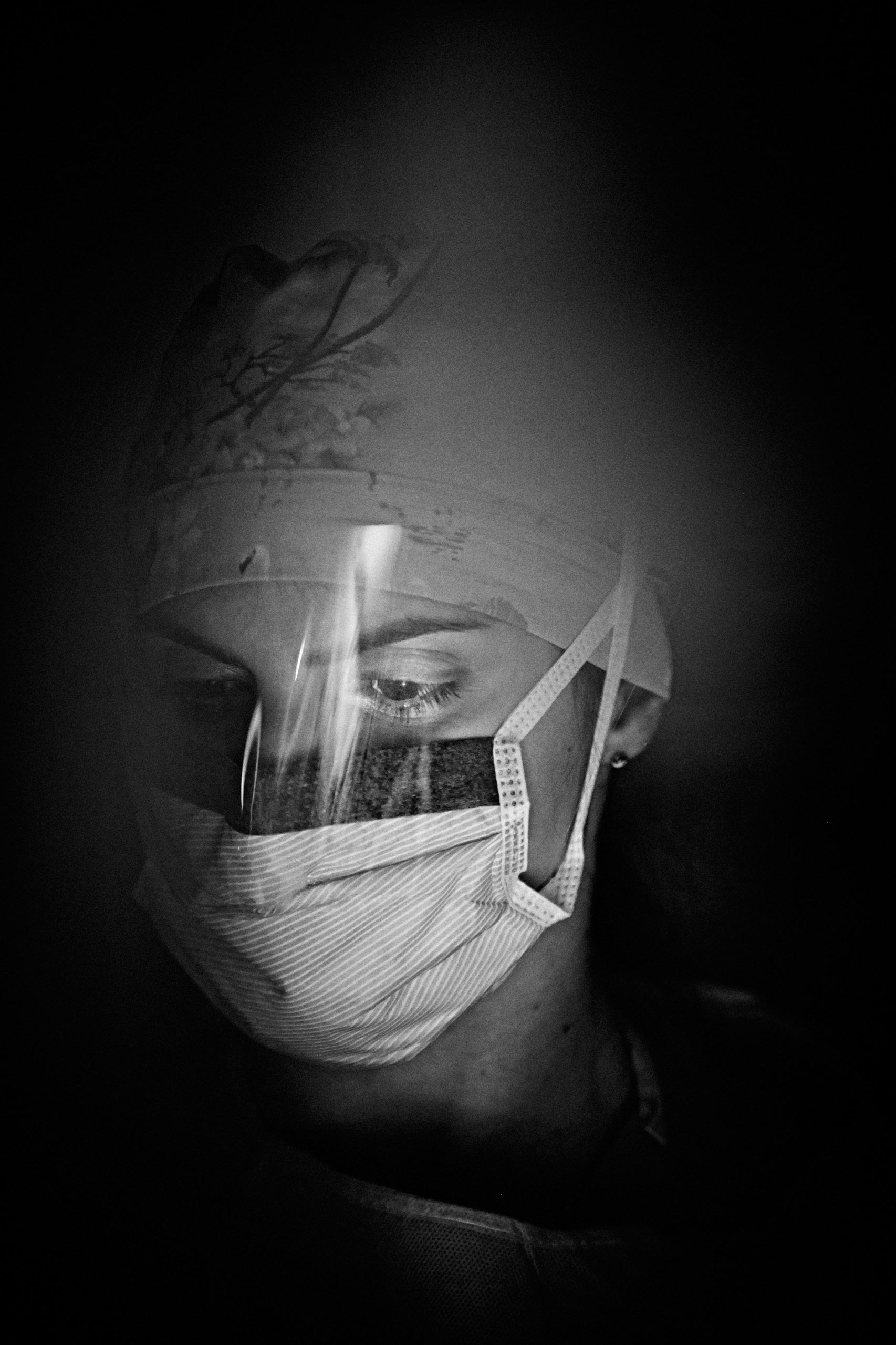

See the Grueling Life of an American Surgeon

The mid-class break offered time to use the bathroom, grab coffee, or simply remain in place and gossip. I preferred to move about, as the lecture hall, with its folding seats, dim lighting, and sticky floor, had the uncomfortable ambience of an old movie theater. On my way out, I chatted with a few people and overheard one group discuss plans to camp out for Duke men’s basketball tickets.

When I re-entered the lecture hall a few minutes later, Dr. Gale, our professor, headed in my direction. Ordinarily, he didn’t socialize with students, so I expected him to walk past without acknowledgment. Instead, he stopped directly in front of me.

“Are you here to fix the lights?” he asked.

The sounds of the classroom seemed to vanish. So did my peripheral vision. Calm down, I told myself, maybe he was talking to someone else and only seemed to be looking at me. I glanced behind me. Nobody there. A few classmates were within hearing distance, but they seemed too engaged in conversation to notice us. Maybe with all the background noise, I had misheard him.

“Did … did you ask me about fixing the lights?” I said.

“Yes,” he replied, irritation creeping into his voice. “You can see how dim it is over on that side of the room,” he said, gesturing with his index finger. “I called about this last week.”

Reflexively, I stroked my chin and looked down at my clothing to check if I seemed out of place. Clean-shaven, and dressed in a polo shirt and khaki slacks, I thought that I’d done a decent job of looking the part of the preppy first-year medical student. Obviously I had failed.

“No,” I said, stumbling to come up with a reply. “I don’t have anything to do with that.”

He frowned. “Then what are you doing here in my class?”

My mouth went dry. Why had he intentionally singled me out in this way? Race was the first thought that entered my mind. I tried to summon an attitude of 1960s-era Black Power defiance, but what came out sounded like 1990s diffidence. “I’m a student … in your class.”

“Oh…” he said.

Dr. Gale looked away, then walked off without another word. I staggered to my seat, sitting through the second part of his lecture like a robot, tuning out his voice. What had started out as a promising day was spoiled.

During lunch a few hours later, I replayed the encounter to three black classmates as we sat out of range of others in the cafeteria. I’m not sure what I was looking for, other than the chance to vent to people who might understand what I was feeling. Their response surprised me: Two of them burst out laughing.

“That’s messed up,” Rob said, almost choking on his hamburger.

“At least he thought you were a skilled worker,” Stan said, as the two laughed harder. “He could have asked you to pick up his trash or shine his shoes in front of the entire class.”

“That’s not funny,” Marsha said, glaring at them.

“What else are you going to do but laugh about it?” Stan shot back.

“He’s right,” Rob chimed in. “You know you want to laugh too.”

Marsha started to say something about reporting the incident or confronting the professor, but her militancy evaporated as Stan and Rob started quoting the comedian Chris Rock. I don’t recall the specific joke, but it made me smile and calmed me down enough that I could eat my lunch. Racial insults—big and small—were a part of our lives and sometimes humor was the best way to deal with it.

Yet the good feelings didn’t last. The afternoon lectures gave way to a different course, and with it, another professor. I could not concentrate at all. “Are you here to fix the lights?” played over in my mind. In high school and college, I had been mistaken many times for a potential criminal, hired help when I was a paying customer, and most favorably, as a six-foot-six budding professional basketball player. But it’s one thing to be insulted by a stranger you’ll never see again, and something altogether worse for your professor—who assigns grades that dictate your future—to cast you in such a limiting way.

Trying to apply reason to the situation, I told myself that at Duke, Dr. Gale saw many more black maintenance workers than black men in his class. And I also firmly believed that there’s no shame in blue-collar work. My dad spent 35 years as a meat cutter at a grocery store while my maternal grandmother—Grandma Flossie—worked her whole life as a housekeeper, or in the parlance of her times, a cleaning lady. What bothered me was Dr. Gale’s assumption that I had no business in his class unless I arrived in some service capacity. Sensitive as I already was about my place a Duke, this incident stabbed at the core of my insecurity. With one question, Dr. Gale had shattered my brittle confidence and my tenuous feeling of belonging at Duke.

—

My racial anxieties intensified. Clearly, Dr. Gale didn’t see me as a Duke medical student, nor was I confident that I could succeed at this level. According to Shelby Steele, a self-described conservative black scholar at Stanford University’s Hoover Institution, this is one of the costs of affirmative action: It “nurtures a victim-focused identity in blacks” and increases their self-doubt as “the quality that earns us preferential treatment is an implied inferiority.” Steele makes some valid points, but his theory did not predict how I responded to Dr. Gale.

The way I saw it, confronting Dr. Gale about the incident seemed like a bad idea because he had final authority over my grade. What would I say to him? How would I expect him to react? Likewise, I felt that reporting the incident to a medical school administrator would prove futile, and possibly even damaging to my future at Duke. His words hadn’t been blatantly racist, and I envisioned that his middle-aged white colleagues would have had trouble understanding why I had interpreted them that way. These influential people were likely to perceive me as a hypersensitive, borderline-militant black male looking to make everything into a racial issue. Given my innate aversion to controversy, that wasn’t the reputation I wanted.

Given Stan’s and Rob’s reaction to the incident—laughter—I doubt my other black classmates would have acted differently. And yet I was furious. I had to do something with that energy in my own way, to show Dr. Gale how wrong he’d been. So instead of taking my case public, I turned inward and did what any good medical student knows best: I studied my ass off.

Day after day, I spent just about every waking hour with textbook in hand. I was determined to prove to each of my professors— but especially Dr. Gale—that I wasn’t a token student admitted to medical school by accident or pity. After class, I headed straight to the library, reviewing my notes and rereading the material until the wee hours of the morning. No matter how enticing the invitations to take a break with classmates, I declined. For those next several weeks, I slept only three or four hours each night.

Other black doctors have traveled this same terrain. In his memoir, Brain Surgeon, Los Angeles–based neurosurgeon Keith Black recounts a similar episode during his medical school years at the University of Michigan in the 1980s. While working under a young physician he perceived as racist, Black was assigned to present a case to the chairman of the department. He prepared more diligently than ever before. “Obviously the chief resident was going to be gunning for me,” Black wrote, “but I decided that I would not live down to his expectations. It was time to stand and deliver.” Black warded off his supervisor’s attacks and impressed the chairman so much so that the chief resident had to give him the highest evaluation possible, setting Black on his path to neurosurgery. Ben Carson, in his first memoir, Gifted Hands, tells a remarkably similar story from his surgical internship of his perseverance in the face of a chief resident from Georgia who “couldn’t seem to accept having a Black intern at Johns Hopkins.”

In the days after the final exams, a nervous energy again pulsed through our class. I knew I had done well on his exam; nonetheless, I was surprised by the result: In my class of 100 students, I had received the second highest score.

Since the final counted twice as much as the midterm, I hoped that I had earned Honors, the grade reserved for the top ten or so students, even though my midterm score was nowhere near the top. I carried my exam to Dr. Gale’s office during his scheduled student hours to find out the verdict. His cluttered office was open for visitors. We were alone to hash out my fate.

This was the first time we had stood face-to-face since our exchange a few weeks earlier. His eyes darted away for an instant as he tugged at his shirt collar. I knew that he recognized me. Surely, he understood that our initial interaction was at least potentially insulting, if not something more. Were the roles reversed, I would have apologized profusely—if not at the time of the mix-up, then definitely the next time we spoke. But Dr. Gale had no such plan.

“How can I help you?” he asked.

I gave him my midterm and final exams and asked whether I had met the cutoff for Honors. His eyes widened as he looked at the final exam score. He removed his glasses and squinted before putting them back on to make sure his vision was not failing. He then stared at my ID card, to see if the name on the exam matched my Duke badge.

“Wow,” he said, unable to conceal his astonishment. “I am very impressed that you scored this high. You’ve definitely earned Honors. You have absolutely nothing to worry about.”

I had imagined this moment from the time I turned in the blue exam books the week before, playing out all the pointed things I might say to put him in his place. But now that it had arrived, all I could do was stand there mutely.

“Congratulations,” Dr. Gale said, his excitement showing no signs of dimming. “This is really incredible. Would you be interested in doing research in my lab?”

I thanked Dr. Gale and told him I would consider his invitation, although I had no intention of doing so. I wanted nothing to do with a professor who could be so dismissive of me one moment, only to change his mind without apology, as if his earlier comments could be erased like chalk on a blackboard. I left Dr. Gale’s office—the last time I ever saw him on Duke’s vast campus—with a confused mixture of pride, relief, frustration, and bitterness. “Are you here to fix the lights?” stirred then—and still today—each of those emotions.

In the nearly 20 years since that episode, Duke has made clear strides on the racial front. Under the direction of admissions dean Dr. Brenda Armstrong, Duke has become one of the most racially diverse medical schools. Many of Duke’s black graduates have gone on to specialize at highly competitive programs nationwide. Perhaps my success and that of others has enabled certain professors to embrace something once unimaginable.

At that time, however, I had no concerns for future black medical students. My victory was strictly personal. No matter what else happened, I had proved to myself, Dr. Gale, and any other doubters that Duke had not erred in accepting me. It didn’t matter whether my classmates were Asian or Jewish, had gone to Stanford or Princeton, or had parents who were surgeons or law professors. I could keep up with them, and rightfully assume my own place as their peer. Affirmative action, despite its flaws, had worked. I had held up my end of the bargain.

But the good feelings didn’t last long. As I transitioned from the classroom to the clinical setting the following year, I was about to witness the far greater struggles of black patients play out before me.

Adapted from Black Man in a White Coat copyright © 2015 by Damon Tweedy. First hardcover edition published Sept. 8, 2015, by Picador. All rights reserved.

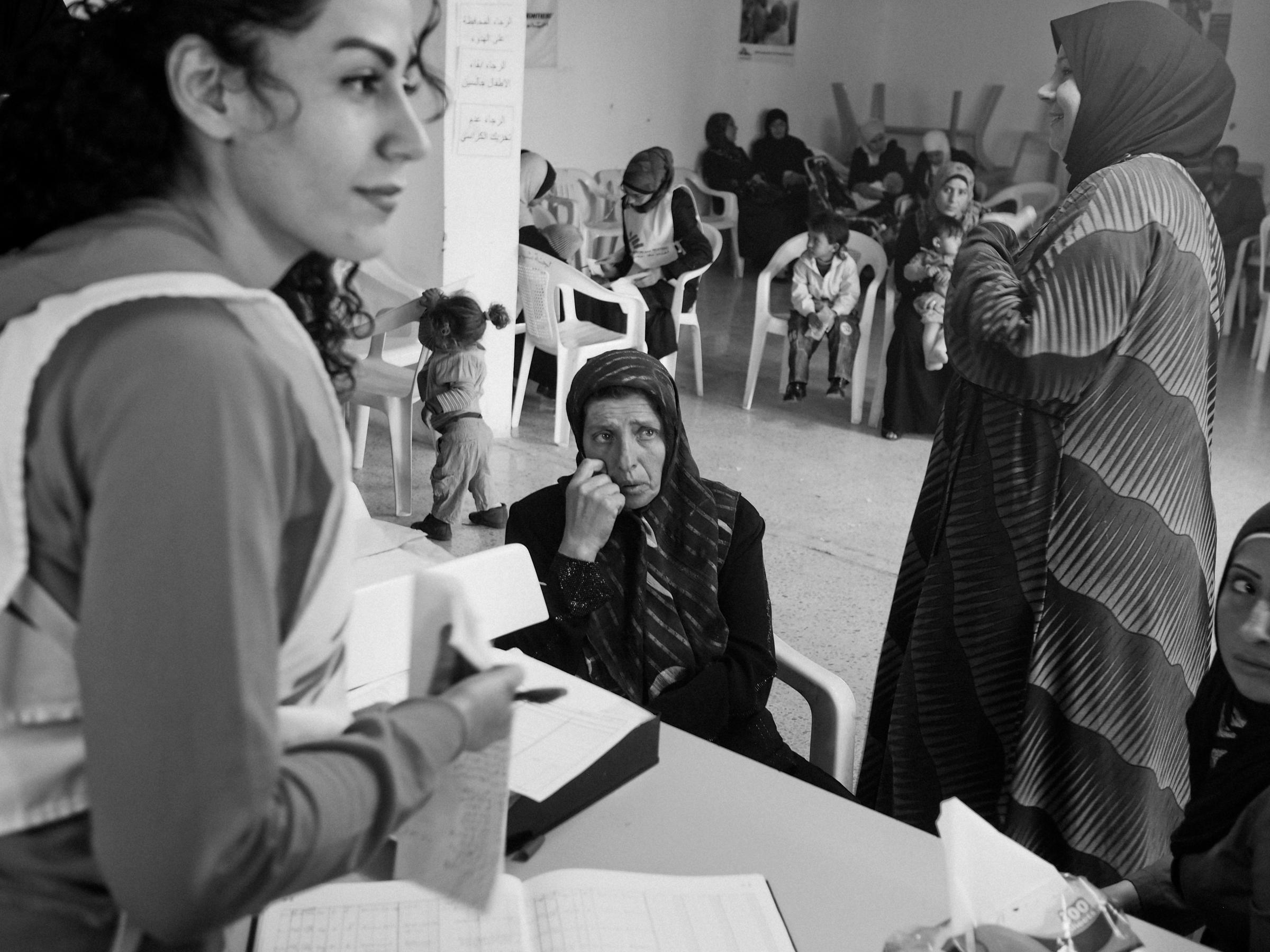

The Reach of War: Chronicling a Day With Doctors Without Borders

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com