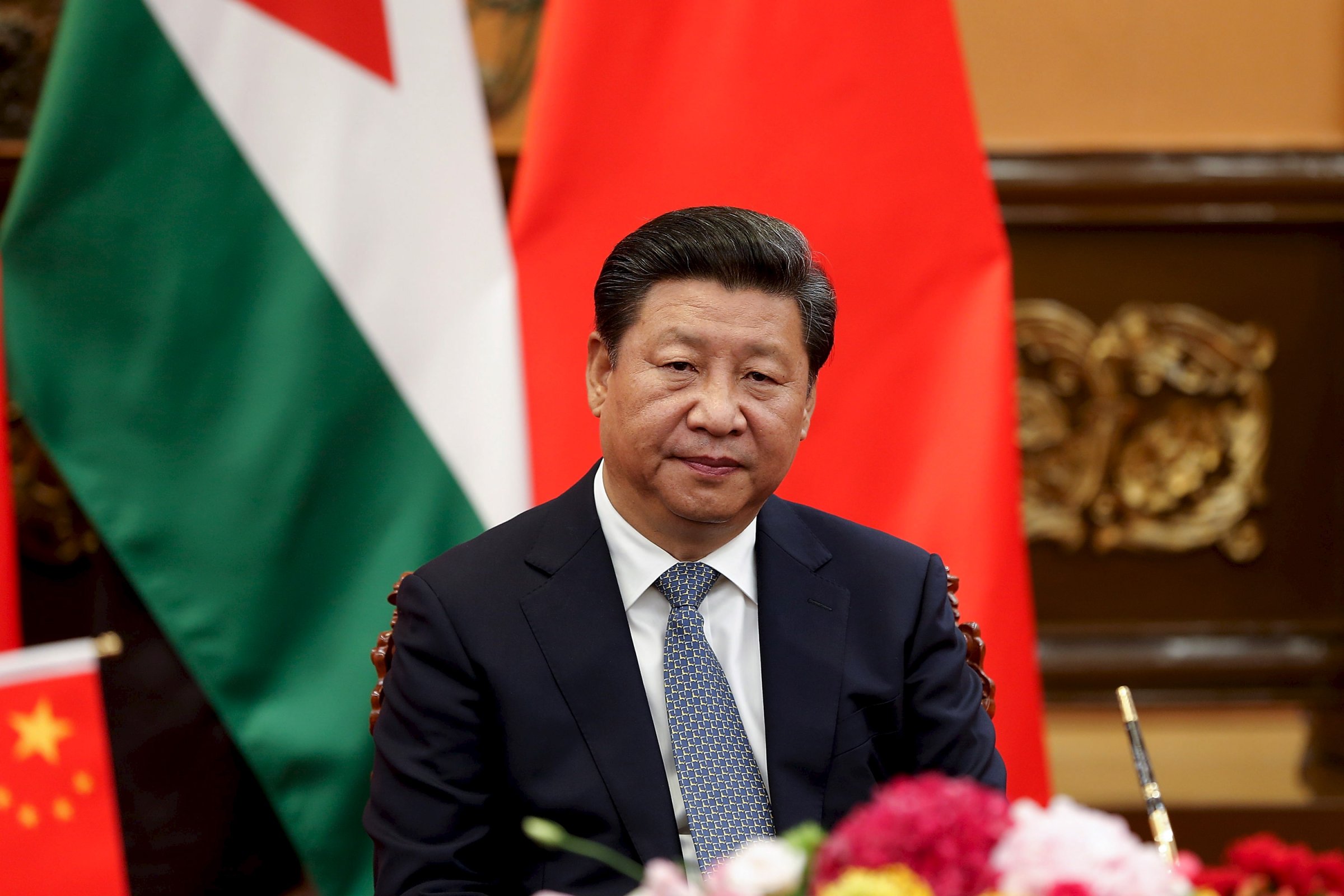

Xi Jinping has visited the U.S. six times before, crisscrossing from Iowa to California. But his upcoming American tour — which begins Tuesday in Washington the state, then heading to Washington the capital before ending in New York City — marks his first state visit as China’s leader. The 62-year-old scion of China’s red aristocracy will meet high-tech and aeronautical executives in Washington State, which exports more to China than any other American state; enjoy a state dinner and 21-gun salute in the nation’s capital; and give his inaugural speech at the U.N. in New York City on Sept. 28.

When the meeting of the world’s two greatest powers was conceived of early this year, President Xi stood on a lofty level. Since taking leadership of the Chinese Communist Party in November 2012, the son of a communist revolutionary has consolidated power faster than his predecessors did. Xi’s anticorruption campaign has won him public support — and also happened to sideline potential rivals. And through his “China dream” sloganeering — which presents communist rule as the culmination of China’s great civilization and links the nation’s rejuvenation with personal prosperity — Xi has worked hard to ensure the ruling party’s longevity.

But the intervening summer has been less kind to the Chinese leader. China’s stock market, through which state-owned enterprises have tried to pump up their assets, has tanked, despite government intervention. The national economy has slowed more quickly than expected. Armies of university graduates cannot find jobs, while laborers demand higher pay for toiling in the factories that powered China’s export-led economy. The official goal is for 7% GDP growth this year, but some economists cannot see how that figure will be achieved without Beijing fixing the numbers. In July, a chemical explosion in the port city of Tianjin claimed at least 160 lives and exposed a corrupt business-government nexus that endangers Chinese citizens.

If the home front is stressful, Xi comes to Washington at an anxious time as well. On the plus side, the world’s two largest emitters appear committed to tackling climate change. Saving the planet is, of course, a noble aspiration. Still, the flush of goodwill that usually develops in advance of U.S.-China summits has been muted this time around. The list of disagreements is long — longer than it was during the last state visit by a Chinese leader four years ago. Washington has expressed frustration with Chinese cyberspying on the U.S. government and American companies; assertive moves by China in the South China Sea, where territorial disputes have embroiled six governments; and a worsening environment for American firms operating in China, which could deteriorate further because of new national-security legislation. And that’s not even mentioning human-rights concerns over Xi’s crackdown on dissenters, which has landed everyone from lawyers and feminists to writers and NGO workers behind bars.

Beijing isn’t happy with the U.S. either. The Chinese government has tired of serving as a punching bag for the GOP’s long list of presidential candidates, who blame China for stealing jobs and roiling the American stock market. (Scott Walker advised Obama to rescind his invite to Xi, while Donald Trump suggested that the Chinese President be fed a McDonald’s hamburger rather than a White House banquet.)

As the world’s second largest economy and its most populous nation, China doesn’t appreciate being lectured to by the U.S. Last week, for instance, Federal Reserve chair Janet Yellen raised concerns about the competence of Chinese policy-makers in dealing with the nation’s economic slowdown. The U.S.’s renewed military commitment to the Pacific smells like containment, no matter what soothing noises the Obama Administration makes. To counteract what Beijing sees as American cultural imperialism, Xi’s administration, particularly his Education Minister, has warned against pernicious Western values infecting Chinese minds. After all, around 300,000 Chinese students are studying in the U.S.; how will they stay loyal if Beijing doesn’t combat hostile foreign forces?

Yet for all their differences, the similarities between the U.S. and China may be what are most detrimental to the bilateral relationship. Both countries conceive of themselves as exceptional, somehow immune to the rules of global geopolitics that constrain other nations. Both countries believe in the superiority of their models of development. Both countries see themselves as forces of ideological good in the world.

“One of the reasons that the United States and China find the other one so difficult to deal with,” says Rana Mitter, director of the China Center at the University of Oxford, “is that they are the only two countries left in the world that tell these big, apocalyptic stories about themselves to themselves and to the world.” Ultimately, the American dream and Xi’s China dream are mutually exclusive visions. No 21-gun salute or swanky state dinner at the White House will change that.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com