Tens of thousands of years ago, early humans made their way from sub-Saharan Africa to Eurasia through a corridor running along the spine of northern Africa. The path through the flatlands of the Sahara later became a trade route; wine and olive oil would come south from the shores of the Mediterranean, while precious stones and gold were brought north. Human cargo traveled along the route as well, with nomads driving caravans of slaves bound for Europe.

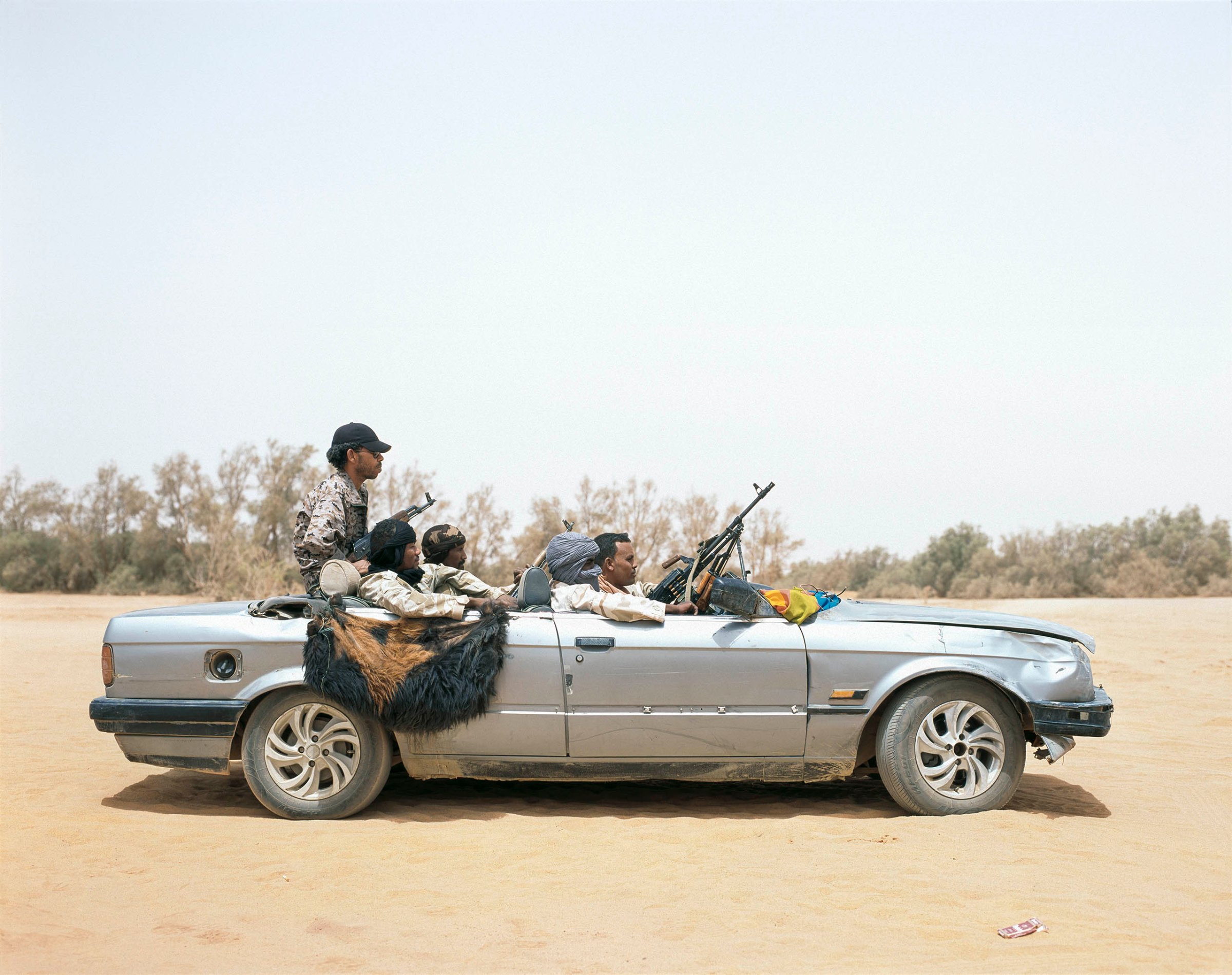

Today, the route connects northern Niger in Central Africa to the sprawling desert region of Fezzan in southwestern Libya. But the lines on the map have become blurred from the violence that has arisen in the aftermath of the 2011 overthrow of Libyan dictator Muammar Gaddafi. The Fezzan has become a largely autonomous land where smugglers run guns and drugs, warring tribes face off and extremist groups take root, as documented in these photographs by Philippe Dudouit. One thing hasn’t changed, though: it is still a pipeline for people, migrants making the journey north to Europe, fueling the refugee crisis now gripping that continent.

Southwestern Libya was a hotbed of trafficking even under Gaddafi’s more than 40-year rule. Criminal gangs took advantage of porous borders with the troubled states of Niger and Chad to the south and Algeria to the west to transport narcotics and arms northward and send subsidized Libyan goods south to sell for huge markups. But the Fezzan remained relatively stable under Gaddafi, who channeled money to develop irrigation and infrastructure in its more heavily populated areas. The major tribes in the region—the Tuaregs and their longtime rivals the Tebus—were broadly supportive of the dictator until the uprising of 2011.

But what little governance there was in the Fezzan came to an end along with Gaddafi’s regime. Two rival governments, the internationally recognized Dignity government based in Tobruk and the Libya Dawn coalition of Islamist militias based in Tripoli, emerged to vie for power in Libya’s north, while rival tribes violently struggle for territory and resources in the Fezzan. In the former military-garrison town of Ubari, hundreds have died as Tebu fighters backed by the Tobruk government clash with Tuareg soldiers said to receive support from Libya Dawn. The Tebus say the Tuareg fighters are jihadists, though Tuaregs insist they are simply trying to defend their homes and their communities.

The power vacuum has already drawn in Islamic extremists like al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb, the terrorist group’s North Africa branch. But the greater threat to global stability in the Fezzan is human trafficking. Just as the Syrian war has contributed to the thousands of refugees now fleeing to Europe each day through Greece and Hungary, the collapse of Libya as a functional state has opened the doors wide for a new flood of human migrants. Tebu militias have allied with criminal groups to ferry migrants into Libya from Niger. The International Organization for Migration predicts that as many as 120,000 people will cross Niger’s northern borders this year as migrants flee failing states and entrenched poverty in West Africa. Many will end up packed into poorly maintained boats on Libya’s northern coast to join the more than 460,000 people who have crossed the Mediterranean into Europe so far this year alone. Some will be scooped up by Western officials en route, but others will drown in the attempt, as over 2,800 migrants have already done this year.

It’s not clear what Western leaders can do to stem the flow of migrants through a lawless region of an increasingly lawless country. On Sept. 14, the European Union authorized military action against people smugglers in the Mediterranean, including the seizure and even the destruction of illegal boats out of Libya. But that will do little to limit the networks of human trafficking farther inland and will not prevent thousands more in West Africa from leaving their homes and traveling north. Extreme poverty remains a powerful motivator.

Meanwhile, the rumbling unrest in Ubari continues to draw Tuareg and Tebu fighters away from border outposts in the Fezzan, creating an opening for human traffickers to expand their networks and for jihadists to recruit displaced youths without access to jobs or education. Adding extremist ideology to a crucible already bubbling with ethnic tensions and lack of governance could produce a yet more dangerous mixture flowing through the channels of these ancient flatlands.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Where Trump 2.0 Will Differ From 1.0

- How Elon Musk Became a Kingmaker

- The Power—And Limits—of Peer Support

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com