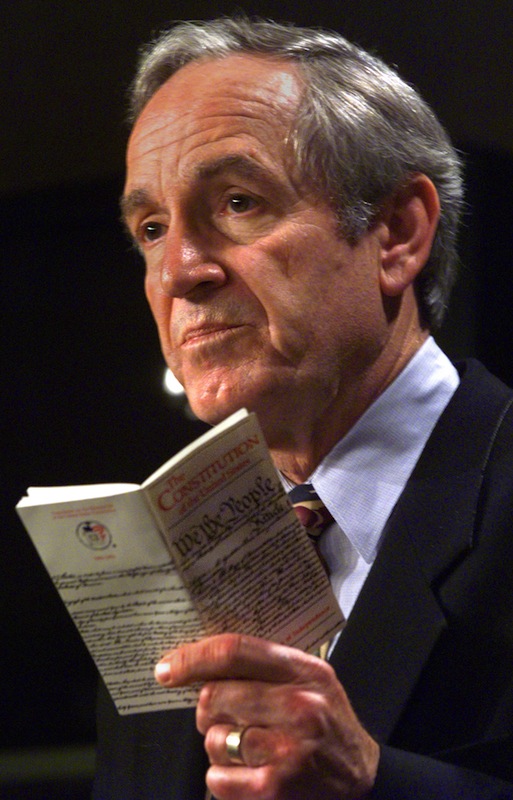

Schools distribute them to young constitutional scholars. Law professors whip them out and quote from them for dramatic effect. They’re a frequent accessory on the campaign trail, and legislators brandish them with pride on Capitol Hill.

And across the nation on Sept. 17, people will turn to their pocket-sized Constitutions in honor of Constitution Day: the 228th anniversary of the Constitutional Convention delegates signing the document in Philadelphia.

But the ubiquitous pocket Constitution has not always been around to keep supreme law at the nation’s collective fingertips. Constitution distribution began two days after its signing, with the first public printing of the document in The Pennsylvania Packet and Daily Advertiser, according to the National Constitution Center. It would be nearly two centuries before the print became truly portable: The earliest reference to an official pocket-sized version appeared 50 years ago, in 1965, as Slate reported in an investigation into how the mini Constitution infiltrated political culture.

That first reference was this resolution, introduced by Rep. Wayne Hays on May 10, 1965:

Concurrent resolution authorizing the printing of a pocket-sized edition of “The Constitution of the United States of America” as a House document, and for other purposes; with amendment (Rept. No. 325). Ordered to be printed.

According to the records of the Government Printing Office Records, the proposal passed and called for 64,500 copies of the Constitution to be distributed between the Senate and House of Representatives.

Now, pocket constitutions are readily available for buying in bulk, with websites often offering single, paperback copies for free in the spirit of democracy. There are high-end copies as well, such as an edition from libertarian think tank The Cato Institute, whose Constitution features red pleather and gold foil cover lettering for those enthusiasts willing to spend five dollars.

Most recently, this June, right around the pocket constitution’s 50th birthday, the House passed a concurrent resolution authorizing the reprinting of the 25th edition of the pocket Constitution. It calls for an unspecified “usual number” to be printed, in addition to 285,400 for the use of the House and Senate. And no representative or senator need worry about not getting his or her own copy: if printing costs are unforeseeably high, the government may print fewer, “except that in no case shall the number of copies be less than 1 per Member of Congress.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Julia Zorthian at julia.zorthian@time.com