If anyone can appreciate a character who throws frequent parties, eats six meals a day, and “whiles away his ‘tweens’ — the ‘irresponsible twenties between childhood and coming of age at thirty-three,’” as TIME once encapsulated the essence of a Hobbit, it’s the American college student. This demographic proved to be J.R.R. Tolkien’s best audience, and the one that elevated him to the status of literary celebrity.

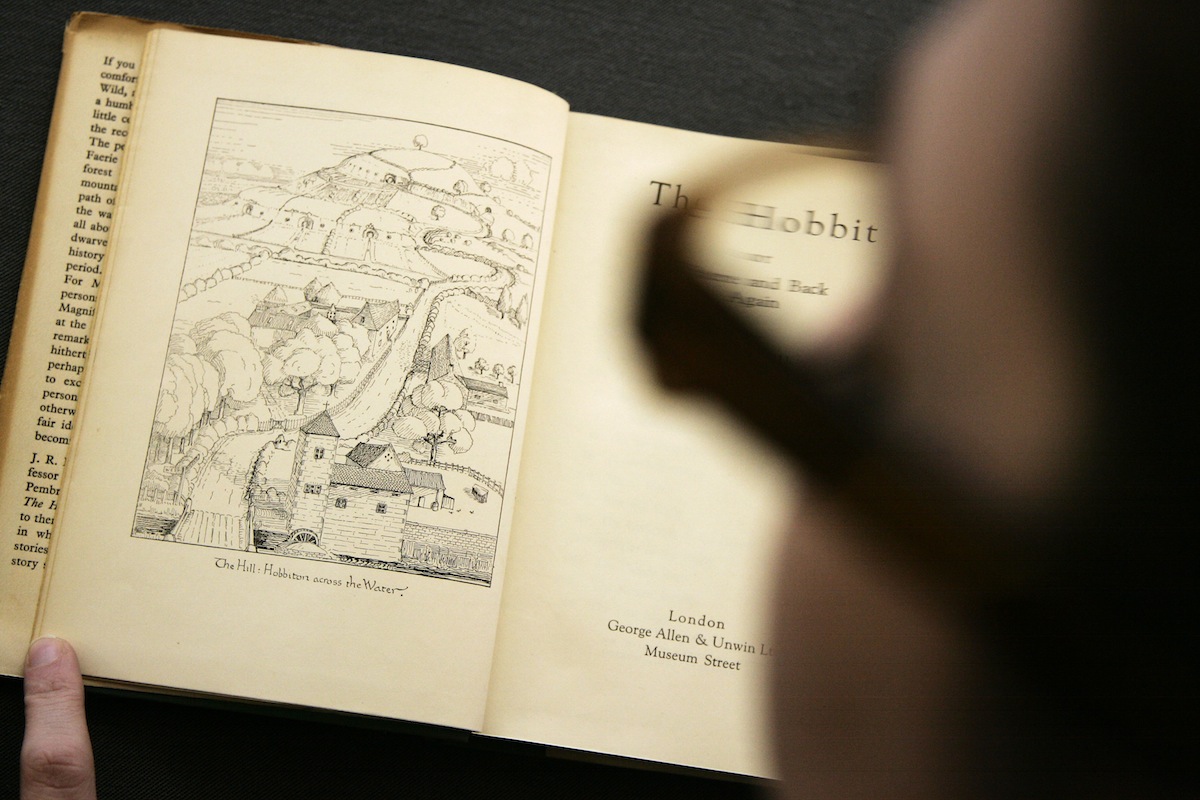

While Tolkien’s first novel, The Hobbit, was published on this day, Sept. 21, in 1937, Hobbits didn’t become household names — at least in the U.S. — for roughly three more decades. By the mid-1960s, however, Bilbo and Frodo Baggins, the reluctant heroes of The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings, had taken college campuses across the country by storm. In 1966, when the paperback edition of the Rings trilogy sold half a million copies in the U.S., one freshman’s mother noted, according to TIME’s report, “Going to college without Tolkien is like going without sneakers.”

TIME, on the other hand, felt that the fantasy novels had more in common with drugs than athletic wear. The 1966 article observes:

The hobbit habit seems to be almost as catching as LSD. On many U.S. campuses, buttons declaring FRODO LIVES and GO GO GANDALF—frequently written in Elvish script—are almost as common as football letters. Tolkien fans customarily greet each other with a hobbity kind of greeting (“May the hair on your toes grow ever longer”), toss fragments of hobbit language into their ordinary talk. One favorite word is mathom, meaning something one saves but doesn’t need, as in “I’ve just got to get rid of all these mathoms.”

Students weren’t Tolkien’s only fans, of course. In its 1938 review, the New York Times called The Hobbit “one of the most freshly original and delightfully imaginative books for children that have appeared in many a long day.” In 1954, TIME described The Fellowship of the Ring as a fairy tale for adults, fueled by a “strong and unorthodox” imagination. But it took the college crowd to make the series a cultural phenomenon. TIME charted Tolkien’s literary journey shortly after his death in 1973, noting:

In the years between 1954, when [The Lord of the Rings] came out, and the present, Tolkien saw his readership spread from a handful of literate Anglophiles … to hundreds of thousands of U.S. college kids who made Frodo a national figure and turned the lore of Middle-earth into a way of life.

There was, naturally, a backlash among the academic elite when Tolkien’s tale took off. “Then, with such popularity,” TIME explains, “the story was denounced as escapist fantasy, its success owlishly attributed to ‘irrational adulation’ and ‘nonliterary cultural and social phenomena.’”

Tolkien took these sour grapes in stride. He did, however, offer a defense that explains why fairy tales attract serious adults—and college students—as well as children: They appeal to the universal desire, in a dangerous and unjust world, for the “consolation of a happy ending,” or what he called Eucatastrophe.

Eucatastrophe, he wrote, provides “a catch of breath, a beat and lifting of the heart, a piercing glimpse of joy and heart’s desire.” It’s the payoff—better than sneakers, and perhaps even LSD—that lures so many readers into the Hobbit hole.

Read more about the 1960s Hobbit craze, here in TIME’s archives: The Hobbit Habit

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com